By Sara Clark. Published June 21, 2018.

Ozma, an endangered aye-aye, in her free-ranging room. Imported from Madagascar in 1991 and estimated to have been born in 1985, Ozma is the DLC’s second oldest aye-aye.

What’s a veterinarian to do when faced with a challenging surgery on a rare species about which no veterinary manuals are written? As the veterinary staff at the Duke Lemur Center have learned, first you evaluate what you have; then you extrapolate from what you know about other species; then you collaborate and improvise!

If you have access to a lemur-sized CT scanner and a 3-D printer, that helps too.

“It was a perfect storm of awesomeness,” says Lemur Center veterinarian Laura Ellsaesser, reflecting on the events that led up to Ozma’s surgery.

This spring, Ellsaesser and DLC senior veterinarian Bobby Schopler collaborated with a local small animal dental practice and an on-campus 3-D printing lab to create a life-size model of their patient’s lower mandible (jawbone). The model, in turn, was used to plan the surgical extraction of a diseased section of tooth in Ozma, an endangered aye-aye lemur.

As there are only 56 aye-ayes living within human care around the world, there was little precedent for such a surgery.

Not only that, but aye-ayes’ dental problems are notoriously difficult to treat. “Their incisors are unusually large and take up most of the mandible,” explains Schopler. “The front teeth actually originate behind the molars.” The sheer size of the incisors means that an infection can track all the way up the tooth to the root, making infections difficult – and at times seemingly impossible – to address.

With the help of the 3-D model, however, the veterinarians were able to pinpoint the issue, conduct measurements, and refine their approach prior to surgery. Not only could they remove the diseased piece of tooth more quickly and cleanly, but they dramatically reduced the time that Ozma was under anesthesia.

“CT scans are nice,” says Ellsaesser, “but using the scans in conjunction with the 3-D model was extremely helpful. It was so much easier to wrap our heads around the issue and the approach by holding, touching, and feeling a life-sized model.”

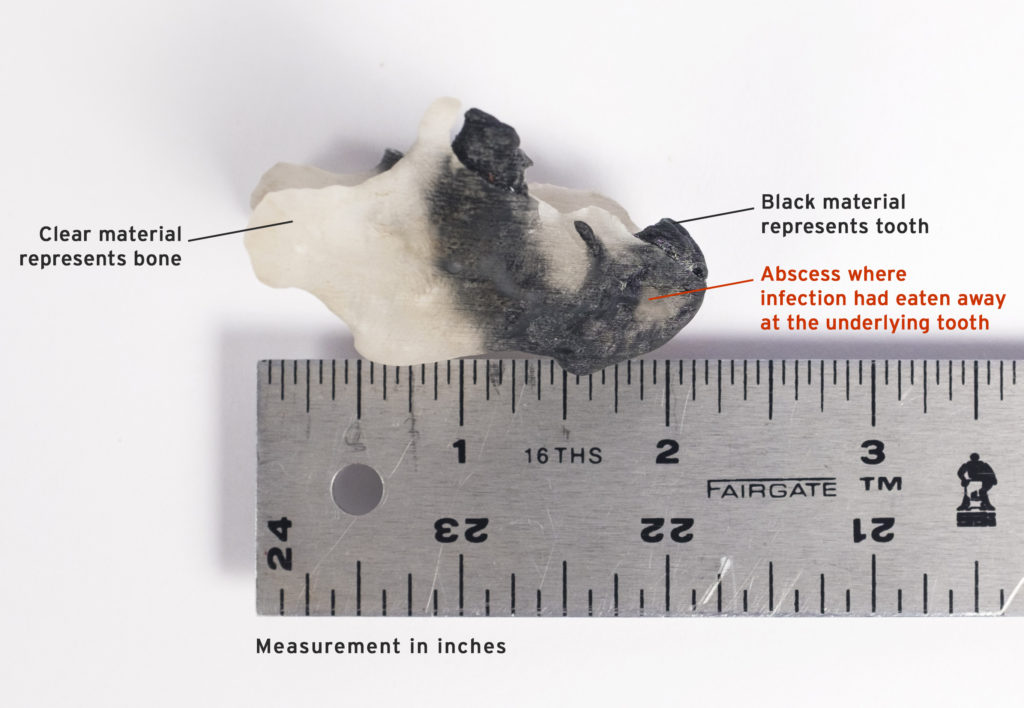

3-D printed lower mandible of Ozma. The DLC vet team collaborated with Chip Bobbert and Susan Whitney, who donated their time to convert Ozma’s CT scans into 3-D printable files. Because the resulting 3-D model was true-to-size and -form, the veterinarians could better visualize Ozma’s problem and plan her surgery more precisely.

Diagnosis and treatment

When Ozma, a 34-year-old aye-aye, developed a dental abscess on the right side of her jaw, the DLC veterinary team drained and treated it, as usual, with antibiotics. When the infection didn’t clear, the 5-pound, 6-ounce lemur was driven to the Veterinary Dental Clinic of North Carolina, where Dr. Don Hoover, Fellow of the Academy of Veterinary Dentistry and the clinic’s owner, had offered the use of his small animal CT scanner.

“Most small animal veterinarians don’t have a CT scanner,” says Schopler, “but Don is a real enthusiast about dentistry. He’s always learning, always pushing the edge of technology.”

In the past, the DLC’s lemurs had been scanned in a CT machine at a human oral surgeon’s office. Because that scanner had been designed for humans to be able to stand upright while being scanned, it posed some challenges for positioning a housecat-sized lemur during a scan. But a CT calibrated for small animals allows for clearer, more detailed images and much easier positioning.

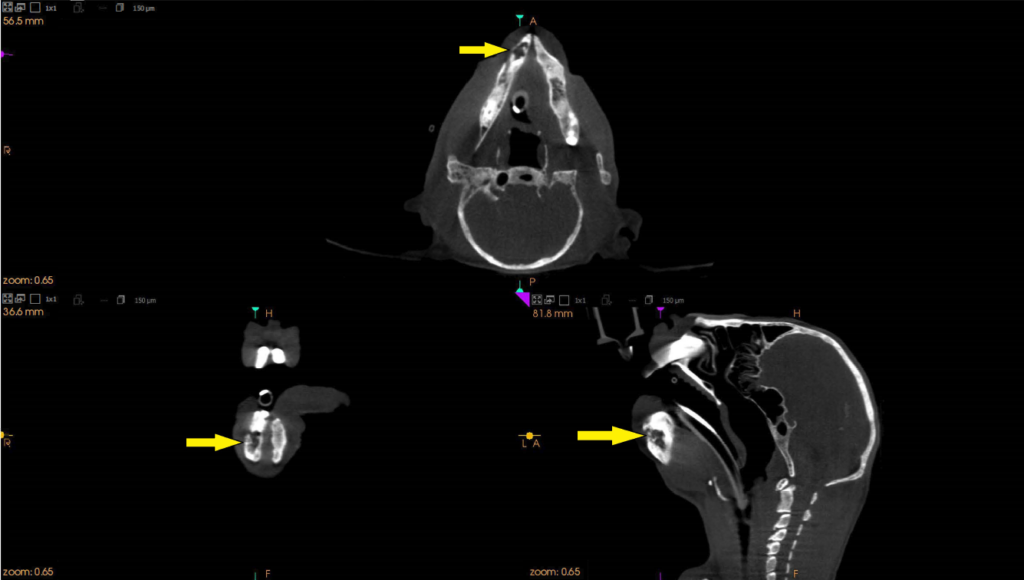

Hoover’s CT scans rendered beautifully, and the team was able to visualize Ozma’s problem more clearly: the aye-aye had a major tooth fragment on the right side of her mouth that was the source of her abscess.

And that, recalls Ellsaesser, was when inspiration hit: “We were all looking at the scan discussing how to approach the surgery when Dr. Hoover said, ‘You should get a 3-D print of this!’” A 3-D print would allow better visualization of the problem and more precise surgical planning.

Coincidentally, Chip Bobbert, a Digital Fabrication Architect at the Duke University Office of Information Technology, was scheduled to visit the DLC that week to help design and 3-D print a new pulley system for the center’s enclosures. The vet team piggybacked on that meeting to discuss making a life-size aye-aye mandible using the scans from Hoover’s CT machine.

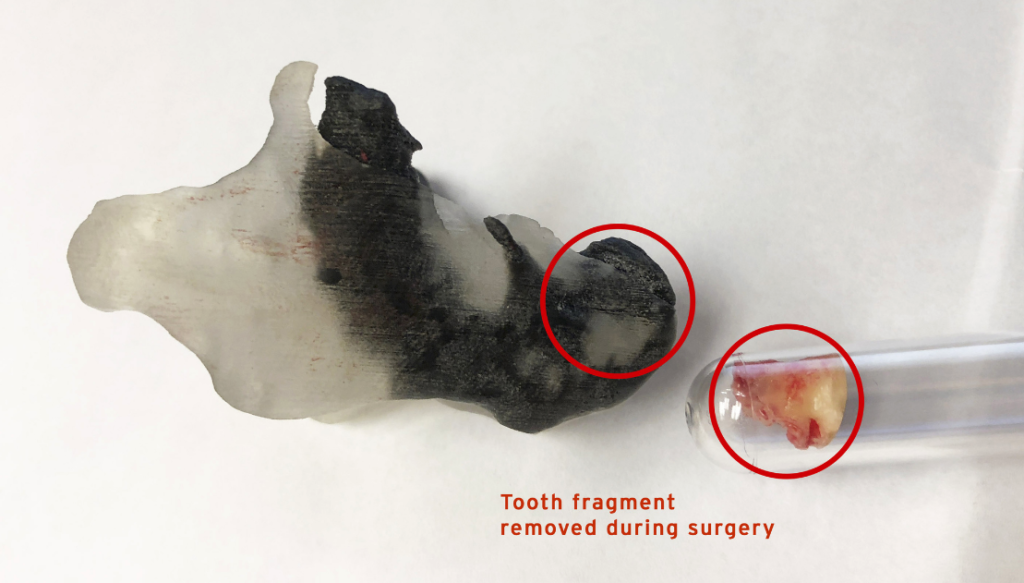

Bobbert’s team agreed to create the model in their 3-D printing lab on campus and soon delivered a prototype to the vet lab. “The prototype was incredible but was all one color. What we really needed was to be able to see what was tooth and what was bone,” says Ellsaesser. So Ellsaesser and Schopler met with Susan Whitney of the Multi-Dimensional Image Processing Lab at Duke Radiology, who converts CT scans into 3-D printable files. “It was amazing watching Susan work, while we sat with her and helped define what we were looking for,” Ellsaesser recalls. A week later, an improved two-color model of Ozma’s mandible was created, which helped the vets better identify what was tooth, what was abscess, and what was bone.

“The clear material is the bone,” explains Schopler, pointing to the model. “The black material represents the tooth. The divots in the bone are where her nerves and blood vessels are – the parts you don’t want to disturb during surgery.”

The model was so detailed and true-to-life, it even enabled the vets to determine where to administer lidocaine before making the extraction. “On the model, we could measure the distance from the point of the mandible up to where the nerve enters the boney canal,” says Ellsaesser. “That distance was 15 millimeters. So we measured 15 mm on a needle, administered the lidocaine, and had a great nerve block. Without the landmark and measurement, we would have been guessing where the nerve was and may not have had a successful block.” Ozma’s heart rate did not increase at all during surgery, indicating that the nerve block had worked and she was feeling no pain.

The entire surgery – from placing the anesthesia monitors and the IV catheter, to administering the nerve block, extracting the tooth, instilling the antibiotic gel, suturing the surgery site and turning off the anesthesia – took only an hour.

“Ozma’s 3-D print was huge in planning her surgery, making it go off without a hitch, and reducing the time she was under anesthesia,” says Ellsaesser. “It was possibly the easiest dental extraction I’ve ever done.”

Ozma has recovered nicely and is back to free-ranging with aye-aye Endora and slow loris Dharma. Schopler and Ellsaesser are pleased with the results: “We’re excited and optimistic that Ozma won’t have any more dental abscesses for a while!”

Ozma. In preparation for the aye-aye’s surgery, the DLC veterinary team consulted experts from a variety of specialties: Don Hoover, owner of the Veterinary Dental Clinic of North Carolina; Chip Bobbert, a Digital Fabrication Architect; Susan Whitney, who converts CT scans into 3-D printable files; and the NC State University College of Veterinary Medicine, who helped the vets select the most appropriate antibiotic and then formulated it into a pluronic gel to be instilled into the area of the abscess after the tooth fragment was removed.

Ozma’s scans were obtained at the Veterinary Dental Clinic of North Carolina, where owner Don Hoover donated his services and the use of his CT scanner to assist with the aye-aye’s diagnosis. In the past, the DLC’s lemurs had been scanned in a CT machine at a human oral surgeon’s office. Whereas the oral surgeon’s scanner was designed for humans, Hoover’s was specially built for small animals to be under anesthesia lying on a table during the scan. As a result, it was easier for the vets to position Ozma properly and it rendered clearer, more detailed images of her mandible.

3-D printed lower mandibles of Ozma (left) and Nosferatu, another aye-aye (right). Both models were created from CT scans taken in Hoover’s office. In Nosy’s model, the clear material represents the bone and the green material represents the tooth. Unlike Nosferatu, whose lower right incisor looks relatively healthy, Ozma had a diseased tooth fragment on the right side of her mouth that was the source of her abscess.

3-D printed lower mandible of Ozma next to the actual tooth fragment removed during her surgery. As demonstrated here, the printed model was true-to-size and -form. “It was so much easier to wrap our heads around the issue and the approach by holding, touching, and feeling a life-sized model,” says Ellsaesser.

3-D printed lower mandible of Nosferatu. An aye-aye’s incisors (front teeth) originate behind the molars and take up most of the mandible. The incisors’ sheer size makes tooth infections extremely difficult to treat.

Lower mandibles of a ring-tailed lemur (left) and an aye-aye (right). Unlike other lemurs such as the ring-tailed lemur, aye-ayes do not have a toothcomb: a dental structure formed by the bottom front teeth that is used for grooming. Instead, aye-ayes have continually growing front teeth like rodents do. No other primate has continually growing front teeth like like an aye-aye’s.

Veterinarian Ellsaesser cleans Ozma’s teeth during one of the aye-aye’s routine dental visits. Aye-ayes’ teeth grow approximately one millimeter per week and because Ozma’s don’t wear properly, hers require occasional trims.

Veterinarians Ellsaesser and Schopler examine Ozma’s teeth during a routine dental exam. The aye-aye has healed beautifully and Schopler and Ellsaesser are pleased with her results. “We’re excited and optimistic that Ozma won’t have any more dental abscesses for a while!”

Did you know…

The Duke Lemur Center’s veterinary team is unmatched in its knowledge of lemur medicine, but we rely on private donations to help cover the cost of vet care, medicine, and new state-of-the-art diagnostic equipment – all of which helps make surgeries like Ozma’s possible. Please consider making a donation today in honor of our vets and their amazing care for the DLC’s lemurs. Your gift at any level makes a difference!