Come Visit the Museum!

The DLC Museum of Natural History is open to the public on select days each month, with options ranging from a free open house to a behind-the-scenes workshop with our experts. Check out our Fossil Tours page for full details on how you can visit the incredible collection at the DLC Museum of Natural History!

What is the DLC Museum of Natural History?

The DLC Museum of Natural History (DLCMNH) is a research collection used to understand our evolutionary journey as primates. Primates are the group of mammals that includes lemurs, monkeys, apes, and humans. For more than forty years, museum scientists have conducted fieldwork around the world, targeting major branches in the primate family tree for deeper exploration. Our collection includes 55 million year-old, lemur-like primate fossils from Wyoming; 37 to 28 million year-old anthropoid fossils from Egypt; 19 to 7 million year-old ape fossils from Egypt and India; 13 million year-old New World monkeys from Colombia; and 10,000 to 500 year-old lemur fossils from Madagascar.

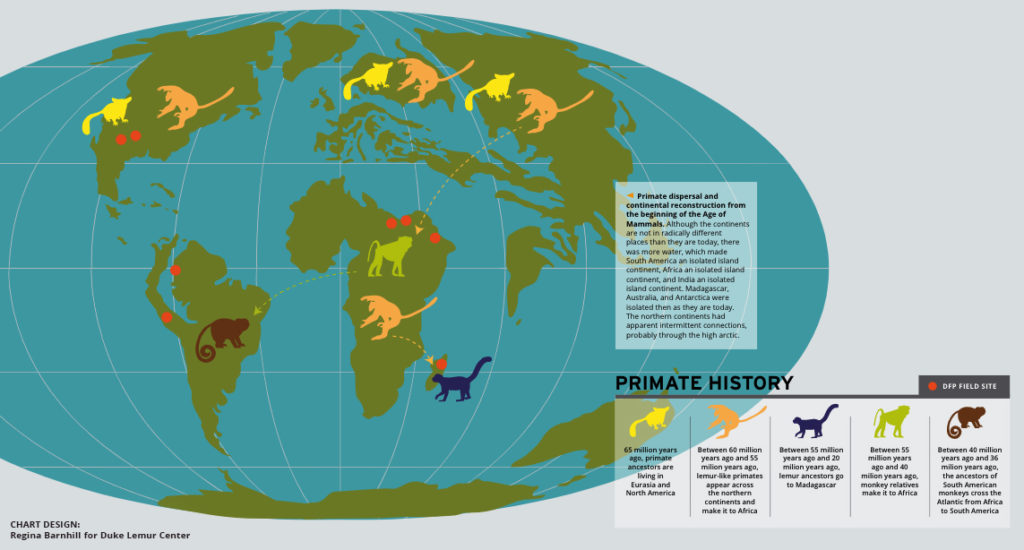

65 million years ago, soon after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs, the primate story was unfolding in North America. From the northern hemisphere, primates found their way to Africa, Madagascar, and South America. Sorting out how they adapted and diversified their way around the globe drives much of the research at the DLC Museum of Natural History, which has field sites around the world (marked above with a red dot). Click anywhere on the image for a larger view.

Because Duke paleontologists are also interested in role the ecosystem played in shaping our primate relatives, many of the 35,000+ specimens at the museum also represent non-primate lineages, including bats, proboscideans (the relatives of elephants), crocodilians, birds, rodents, carnivorans, sharks, and anthracotheres.

In addition to its fossils and subfossils, the museum is responsible for a collection of osteological specimens from the Duke Lemur Center. These specimens are from vouchered animals that died of natural causes at the DLC. This unique collection associates the detailed life-history of each animal housed at the DLC with skeletal specimens that can be used to understand how life-history factors affect hard-tissue development.

The center also maintains an extensive digital museum at MorphoSource, an online digital specimen repository initiated by Duke Evolutionary Anthropology professor Doug Boyer, sponsored by the National Science Foundation, and hosted by Duke Libraries. Researchers and the general public are welcome to explore our MorphoSource collections and to request downloads of DLCMNH specimen scan data. The terms of use for digital data – including scans, 3D models, and photographs – can be found here.

We are currently the DLC Museum of Natural History, formerly the Division of Fossil Primates (DFP); but our accession prefix is DPC, an abbreviation of “Duke Primate Center,” the former name of the Duke Lemur Center (DLC). Despite the changes in name and slight change in mission, we continue to use DPC for all specimens curated by the Division. For more information on our specimen number method see the Information For Researchers below.

GENERAL INFORMATION

Primates are a specialized group of animals that share many features including relatively large brains, grasping hands, and complex social lives. Here at the DLC we have two large populations of primates: the lemurs that live at the Lemur Center full time, and the humans who study and protect the lemurs. But how are these primates related to each other? What does everything we are learning about lemur diets, diseases, physiology, and social behavior tell us about being a primate or being a human?

In order to explore the biological connections between lemurs and humans, we need to turn to the fossil record to help us understand the evolutionary journey of our primate relatives. Duke researchers and their national and international collaborators target branches along the primate family tree, going out into the field to find evidence of fossil primates and the ancient ecosystems they called home.

The DLCMNH is off campus, both for the Duke Lemur Center and Duke University. Our current address is:

1013 Broad Street

Durham, NC 27705

We are located just north of Duke's East Campus, directly across the street from the Willow Oak Veterinary Hospital. If you are visiting us with a car, pull into the driveway on the north side of the building and park in the small lot behind the DLCMNH. Parking does not require a parking pass. If the lot is full, there is plenty of street parking on Broad Street. Just ring the doorbell by our front door or knock on our side door.

We are now offering small, guided tours of the DLC Museum of Natural History! The Museum is located on Broad Street in Durham, NC, about 10 minutes from the Lemur Center's main campus. As with all tours at the DLC, reservations must be made in advance. Please visit our fossil tours homepage to book your visit.

The DLCMNH has an active volunteer program. Please visit the DLC's volunteer homepage and scroll down to the Museum of Natural History section to find out about opportunities to help us conserve and research the fossil collection.

Donations play a huge part in the curation and preservation of our fossil specimens and in field expeditions of our Department. If you wish to make a donation, please click here or feel free to contact our office directly. We would love to hear from you!

The DLCMNH also maintains a wishlist of items that can be purchased directly via the Duke Lemur Center’s amazon.com wishlist. (Look for items designated for fossil of DLCMNH use.) Select an item from the wishlist, and your gift will be sent directly to the DLCMNH! Be sure to include your name and email address in the notes field so we can send a thank-you.

A special thanks to the following for their generous financial support:

Ann and Gordon Getty Foundation

Trish Kohler

Ben Freed

Elaine McNeil

Richard Kay and Blythe Williams

In addition, we'd love to thank those who purchased magnifying glasses, a color chart, and other DLCMNH-related items from the amazon.com wishlist this year. We're so grateful!

Fossil Friday blog posts highlight fossils and subfossils within the DLCMNH collection. Visit the Fossil Fridays archive HERE.

For decades, the DLC's fossil collections have provided a research resource to the world, yet only a few non-paleontologists have heard of the collection or the countless ways its more than 35,000 specimens can provide insights for scientific studies. With the goal of increasing awareness of the collection for a variety of potential new users—students, educators, scientists, and curious lifelong learners—we will be changing the name "Division of Fossil Primates" to the DLC Museum of Natural History.

In preparation for this, our fossil team has been working with the DLC Education and Outreach team to design an exhibit that tells the epic story of primates, from their origin after the extinction of the dinosaurs to today, when most primate species are on the verge of extinction. The exhibit will also be a tool for virtual classroom tours and programming. We're excited to share the collection with a wider audience through this new DLC exhibit.

The year 2020 also brought new discoveries to the fossil collection, while researchers and the public continued to explore our online specimen collection at morphosource.org. The online collection was visited tens of thousands of times, and hundreds of specimen download requests were fielded from students, researchers, and educators.

The DLC fossil collection also received two federal grants totaling $800,000+ to support our efforts to preserve and share the collection.

To read more, please visit our 2020 Impact Report.

INFORMATION FOR RESEARCHERS

We encourage researchers to help us make the DLCMNH an active collection where innovative research is taking place. We are open to Duke researchers and to non-Duke researchers. We especially encourage undergraduate and graduate students to utilize our fossils and osteological specimens as part of their research projects.

Researchers interested in visiting the DLCMNH and examining the collections should submit our Information Request Form at least two weeks prior to your intended visit.

The DLCMNH is in the process of developing an online catalogue of our fossil databases. Researchers should contact the Curator directly for more extensive specimen lists until the catalogue is available online.

General inquiries and requests can also be sent to duke_fossil_lab@duke.edu. Research visits to the vertebrate paleontology lab at the Division of Fossil Primates should be conducted during regular business hours (Monday-Friday, 9:00 a.m. until 5:00 p.m.).

In an effort to make our collections available to researchers who cannot travel to Durham, we have an extensive digital museum through MorphoSource. If you are interested in downloading scans or models of fossils, please submit your request using our Information Request Form.

In an effort to assist in the digitization of the DLCMNH collection, researchers will be asked to share digital images and scans of DLCMNH fossils generated during a research visit. Any DLCMNH fossil scans or 3D surface models will be added to the DLCMNH MorphoSource page. These models can be made public when the fossils are published.

After a manuscript is accepted for publication, researchers should contact the DLCMNH for an internal publication number that should be added to the acknowledgment section (for example, “This is Duke Lemur Center publication #1332”). This helps us track studies that use DLCMNH specimens and it helps us secure funding to conserve the specimens.

DLCMNH material on loan should not be transferred to others or molded/cast without prior discussion and permission. A copy of any casts made should be returned to the Museum.

In order to avoid conflicts of research interest, research proposals will be reviewed and, where appropriate, approved by the DLCMNH research committee.

Image © Duke Photography

We are currently the DLC Museum of Natural History, formerly the Division of Fossil Primates (DFP); but our accession prefix is DPC, an abbreviation of “Duke Primate Center,” the former name of the Duke Lemur Center (DLC). Despite the changes in name and slight change in mission, we continue to use DPC for all specimens curated by the Division.

Specimen numbers should be rendered as “DPC_####”; that is, DPC(space)specimen number.

Osteological specimens at the DPC are given the specimen prefix “OST.” Those specimens should be recorded as “DPC_OST_###”

We also integrated Miocene fossils from Colombia into the DLCMNH collection. These specimens were collected under research permits issued to Dr. Rich Kay and rehoused at the DLCMNH with an NSF grant (NSF DBI 1458192). The original institutional abbreviation for the La Venta material was expressed as “IGM_####.” Now that the material is part of the Museum, the specimen numbers should be rendered as “DPC_IGM_####

The DLCMNH maintains an extensive cast collection for comparative research and instruction. These casts (abbreviated C) are rendered as “DPC_C_Original_Specimen_prefix_and_number” in our catalogue to make it clear where the original specimen is housed.

DLCMNH STAFF

Dr. Borths is Curator of the DLC Museum of Natural History. He earned his bachelor's degrees from The Ohio State University (Geological Sciences and Anthropology) and his Ph.D. from Stony Brook University (Anatomical Sciences).

Matt is a paleontologist who studies the evolution of animals in Africa, particularly the evolution of carnivorous mammals -- including some of the oldest meat-eaters to chase down our primate ancestors. He has been part of field projects in Egypt, Madagascar, Oman, Kenya, Tanzania, Wyoming, and North Dakota. Matt is the co-creator of Past Time, a project that uses a podcast, blog, social media, and virtual classroom visits to teach non-specialists about the paleontology and the scientific process.

Matt's CV can be viewed HERE.

Email: matthew.borths@duke.edu

Catherine is the Collections Manager at the DLCMNH, which means she wears a lot of hats! She is the assistant to the curator and is the DLCMNH collections manager. Catherine is also in charge of keeping the DLCMNH on track financially as well as helping with grants. If you’re visiting the collection, Catherine will help coordinate your visit, and if you need a loan from the museum she will help get the specimens to and from your lab. She also helps schedule work-study students and volunteers.

Catherine is a member of the Society for the Preservation of Natural History Collections (SPNHC), where she coordinates with other collections managers to ensure the longevity of the DLCMNH. Her favorite part of working at the museum is seeing people, especially kids, get excited about fossils.

Email: criddle@duke.edu

Karie is the Fossil Preparator at the DLCMNH. She works to uncover fossil specimens from the rock they are encased in, making sure they are sturdy enough to be studied by researchers. As preparator, she also makes molds and casts (exact copies) of fossils for display in museums. Karie started her fossil preparation journey at the University of Michigan where she earned her B.S., then continued on to be fossil preparator at Ohio University where she earned her M.S.

Karie has been to Madagascar on research every summer since 2015, and she can speak Malagasy (the language of Madagascar). She recently spent nine months there on a Fulbright grant to study sustainable rice agriculture near Maromizaha protected area – home to critically endangered lemur species such as the indri. Karie is excited to merge her interests in fossils and the environment of Madagascar by working at the DLCMNH!

Kathleen Muldoon, Ph.D.

Doug Boyer, Ph.D.

Erik Seiffert, Ph.D.

Hesham Sallam, Ph.D.

Richard Kay, Ph.D.

DETAILS OF THE COLLECTIONS

DLCMNH fieldwork has taken place in Egypt for over 30 years, and we hope to continue this work by collaborating with Egyptian paleontologists and geologists. The near-shore marine and continental sediments in the Fayum area span the middle Eocene through early Oligocene. At the time the fossils were deposited, Afro-Arabia was tectonically isolated from Eurasia. The Fayum contains a large diversity of primates, including over 20 species of early anthropoids as well as some of the earliest records of strepsirhines (living lemurs and lorises) in Africa.

Besides primates, the Fayum mammal collections at the DLCMNH include marsupials, bats (at least 11 species), hyaenodonts (20+ species), hyraxes (20+ species), elephant shrews, rodents (10+ species), proboscideans, sirenians and whales, and a number of enigmatic groups found nowhere else in the world. Including non-mammalian species, the DLCMNH Fayum collection consists of nearly 20,000 specimens.

Wadi Moghra is an important 19 million year old locality near El Alamein in northern Egypt. The DLCMNH Wadi Moghra collections are the only sample of this fauna outside of Cairo. When the Wadi Moghra fossils were deposited, Eurasia and Africa tectonically contacted each other. The vertebrates from Wadi Moghra are among the first records for a new wave of immigrants from Eurasia (perissodactyls, artiodactyls, carnivorans) that entered Africa at the beginning of the Miocene. This is also the interval when Old World monkeys (i.e. baboons, colobus monkeys) and apes split from each other. Systematic, functional, biostratigraphic, paleoclimatic and biogeographic studies of these large collections are on-going.

During the early Cenozoic, the ancient ancestor of lemurs dispersed from mainland Africa across the Mozambique Strait to Madagascar. Once in Madagascar, lemurs diversified into dozens of species. Today, lemurs are among the most endangered mammals in the world as human population growth and agriculture push the primates into smaller habitats on the island.

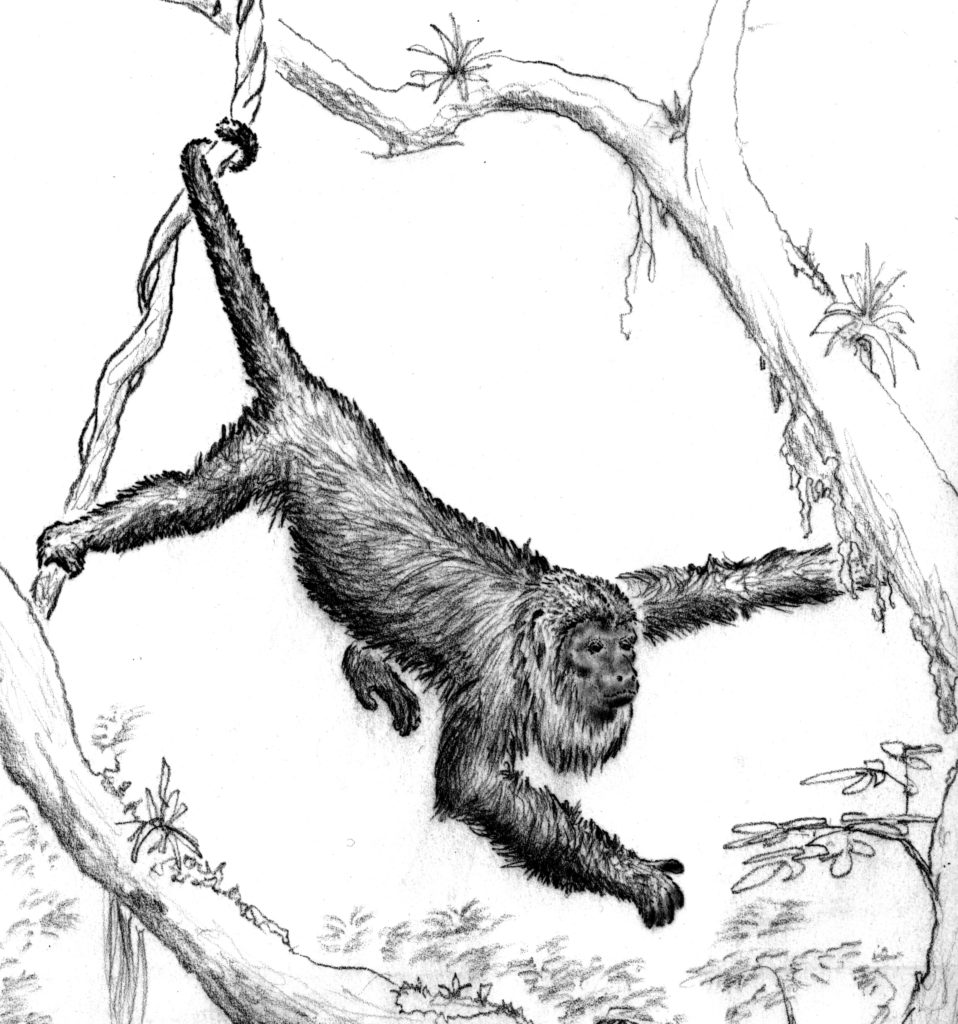

The fossil record of Madagascar reveals that until relatively recently, lemurs were even more diverse than they are today. The DLCMNH subfossil lemur collection is one window into the ancient diversity of lemurs that included the gorilla-sized giant lemur Megaladapis, the sloth-like lemur Paleopropithecus, and the terrestrial, monkey-like lemur Archaeolemur.

The DLCMNH Madagascar project has been ongoing since the late 1980s. Subfossil (500 to 10,000 year-old) specimens of primates and other vertebrates are collected from caves in limestone karst regions and from swamp deposits at a variety of sites across the island. Work carried out so far has led to recovery of some of the most complete skeletons known for many of the giant extinct lemurs. More than 2,000 specimens from Madagascar are housed at the DLCMNH.

Research is focused on the extinction of subfossil mega- and micro-fauna, documentation of evolving habitats across space and time, functional studies of extinct giant lemurs, and ancient DNA and isotopic analyses of extinct as well as subfossil representative of extant species. With this information, DLCMNH researchers and collaborators hope to understand the dynamic changes that have occurred across Madagascar since the arrival of humans. With this information we work with community conservation researchers through the DLC-SAVA Conservation project and other organizations to use past extinctions to understand the current biodiversity crisis in Madagascar.

The geologically oldest collection at the DLCMNH from the latest Paleocene and earliest Eocene of North America (~55 through 48 million years ago). During this interval, average global temperatures were very high, creating tropical ecosystems at high latitudes. Fossils collected from sediments in Wyoming reveal the lineage that includes lemurs (strepsirrhines) and the lineage that includes humans (haplorhines) had split and were diversifying as primates assumed the ecological roles they continue to occupy today.

The early Cenozoic collections at the DLCMNH are used by researchers to probe the early anatomical adaptations that allowed primates to become such a widespread lineage. Wyoming specimens also help to document the arrival of other groups of mammals (perissodactyls, artiodactyls, rodents, carnivores) in North America. The collection is used to document how different animal lineages changed through the Paleocene-Eocene Thermal Maximum (PETM), an interval of rapid climate change that serves as a model for interpreting how modern ecosystems respond to changing global climates.

DLCMNH fieldwork in Wyoming has been ongoing since the 1980s and continues to be carried out each summer in conjunction with the Evolutionary Anthropology and Biology Departments at Duke.

During the Oligocene, one lineage of anthropoids dispersed from Africa to South America where they diversified into the platyrrhines (New World monkeys). Then, South America was an island continent and it was populated by unique mammal lineages like notoungulates and American metatherians. The record of this faunal diversification is preserved in the La Venta collection from the Miocene of Colombia. Through years of fieldwork, Dr. Richard Kay, Professor of Evolutionary Anthropology at Duke University, discovered and studied the fossils that were recently accessioned in the DLCMNH collections.

The DLCMNH maintains an extensive collection of osteological specimens and a large cast collection that documents the morphological and taxonomic diversity of primates through the Cenozoic and into modern landscapes. One of the most remarkable aspects of the osteological collection is that many of the specimens were once part of the living collection at the DLC. Detailed records of the life history of each animal are maintained by the DLC including the animal’s weight, diet, and social status. Further, many of these animals were part of non-invasive locomotion and cognitive studies at the DLC. This collection directly connects each of these biological variables to the bones of individuals. Scans and measurements from these specimens can be utilized by researchers to interpret the behavior and ecology of extinct primates.