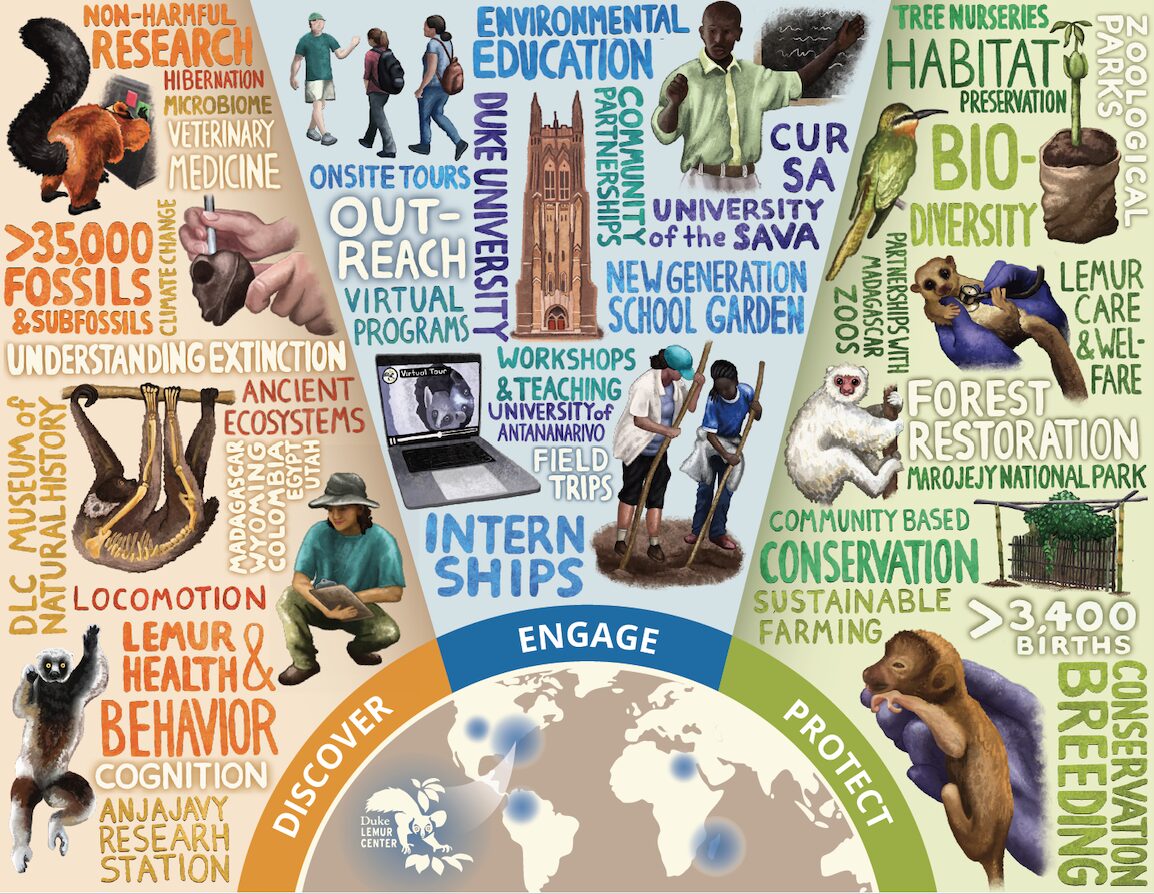

A truly global institution, the Duke Lemur Center works in the United States in North Carolina, Wyoming, and Utah; La Venta, Columbia; Santa Cruz Province, Argentina; Wadi Moghra and the Fayum Depression, Egypt; and in numerous fossil and conservation sites across Madagascar. Artwork by Talia Felgenhauer, 2023-24 Undergraduate Fellow in Communications. Click for a larger version.

Founded in 1966, the Duke Lemur Center (DLC) is an internationally acclaimed non-invasive research center housing nearly 250 lemurs and bush babies across 12 species—the most diverse population of lemurs on Earth, outside their native Madagascar.

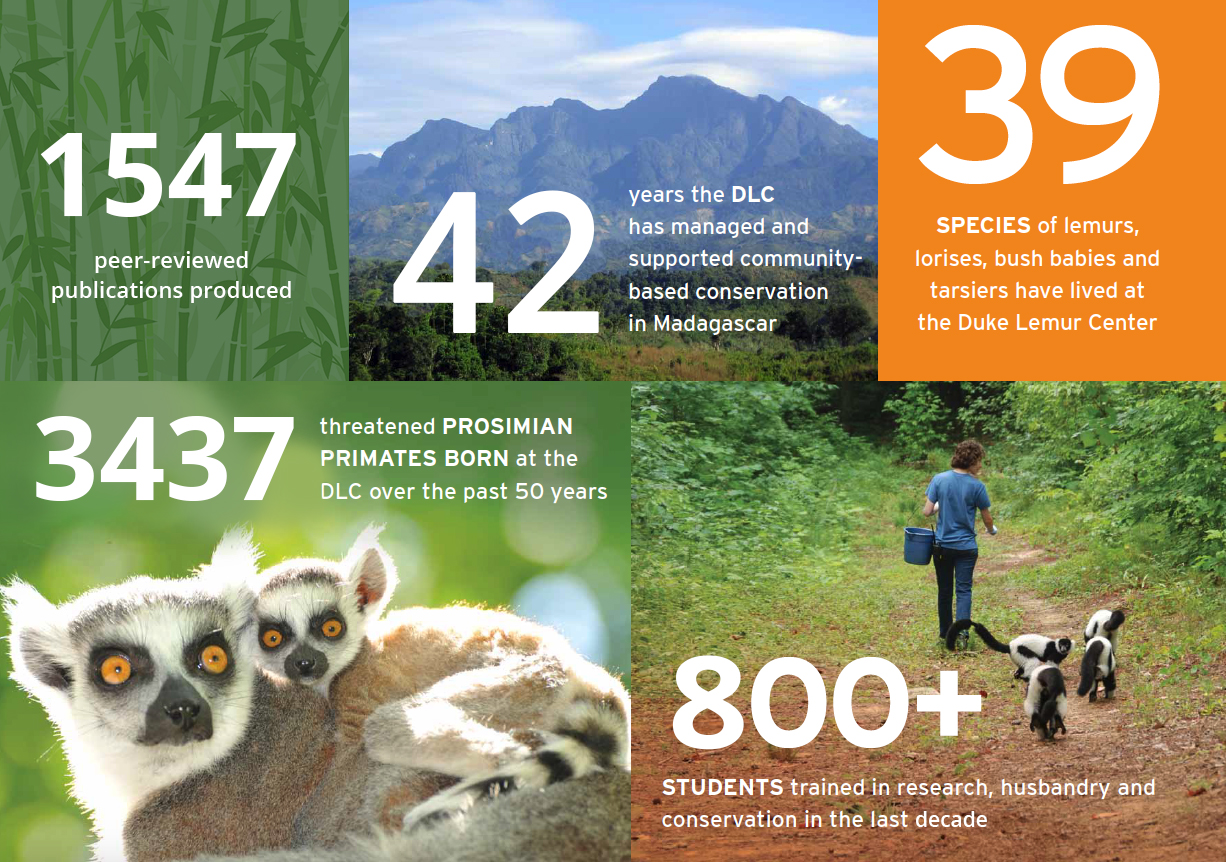

The DLC is open to the public and educates more than 35,000 visitors annually. Its highly successful conservation breeding program seeks to preserve vanishing species such as the aye-aye, Coquerel’s sifaka, and blue-eyed black lemur, while its Madagascar Conservation Programs study and protect lemurs—the most endangered group of mammals on Earth—in their native habitat. The DLC Museum of Natural History examines primate extinction and evolution over time and houses more than 35,000 fossils, including extinct giant lemurs and one of the world’s largest and most important collections of early anthropoid primates.

Accreditation

The Duke Lemur Center is accredited by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums (AZA), which means it meets the highest standards for animal welfare, health, and nutrition. To maintain AZA accreditation, the DLC must pass an assessment every five years. At our inspection in 2021, the DLC received an extremely rare perfect score.

The Duke Lemur Center is also accredited by AAALAC International, which means it meets the highest standards for animal welfare, health, and nutrition for animals used in research. (All DLC research is non-invasive.) AAALAC-accredited institutions like the DLC help raise the global benchmark for animal well-being in science. To maintain AAALAC accreditation, we must pass an assessment every three years.

The DLC is proud to be the only organization in the world that holds accreditations from both the AZA and AAALAC International.

Why Lemurs?

Of all the animals on Earth, why are we so passionate about lemurs? Of all the islands in the ocean, why is Madagascar remarkable—and so worthy of our conservation attention?

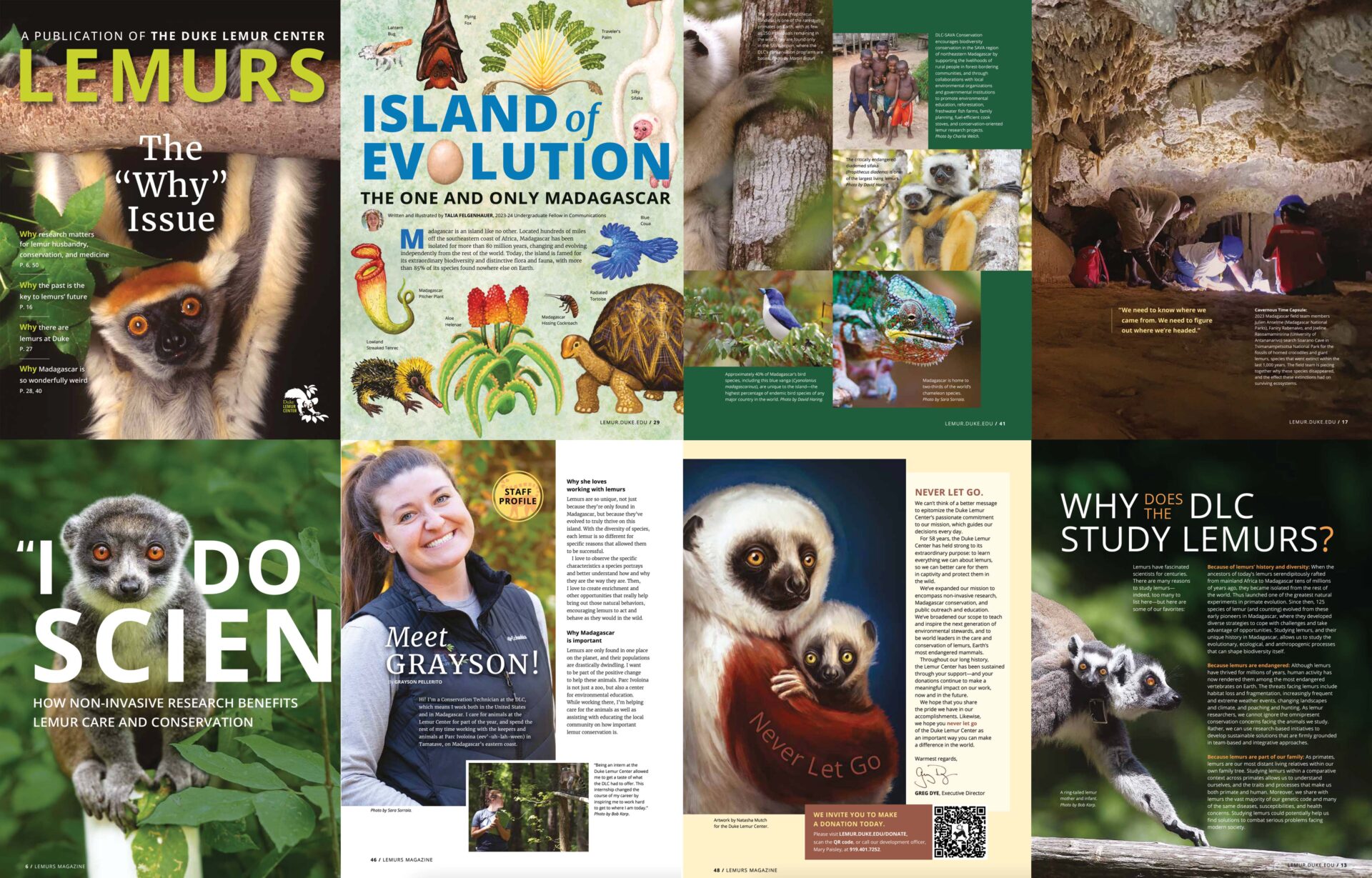

The “Why” issue of the our official magazine addresses the core mission of the DLC: Why do we do what we do? Featuring articles from DLC staff, interns, and collaborators and gorgeous images from our volunteer and staff photographers, this issue is infused with the curiosity, beauty, and tenacity that define the DLC. The entire issue, as well as past issues, can be read free online.

History

The DLC was established over 50 years ago as an opportunistic collaboration between two researchers: John Buettner-Janusch of Yale University, who was studying biochemical genetics in lemurs; and Peter Klopfer, a Duke University biologist studying maternal behavior in mammals. Together, the two biologists conceived the idea of establishing a primate facility in Duke Forest that would combine their research perspectives in order to explore the genetic foundations of primate behavior.

Peter Klopfer is embraced by DLC Director Anne Yoder at the Lemur Center’s 50th Anniversary Scientific Symposium in 2016. Klopfer, biologist and co-founder of the DLC, was a member of the search committee that hired Buettner-Janusch onto faculty at Duke. “B-J” accepted the position, on the condition that the University provide accommodations for his lemurs and other primates.

Bill Anlyan, then dean of the Duke University School of Medicine, granted a large swath of Duke Forest to the project, and the National Science Foundation provided the funds to build a “living laboratory” where lemurs and their close relatives could be studied intensively and non-invasively. In 1966, the nascent DLC—then called the Duke University Primate Center—was founded on 80 wooded acres (later expanded to 100 acres), two miles from the main Duke campus. Buettner-Janusch’s colony of lemurs was relocated from Connecticut to North Carolina, and the DLC began assembling the largest living colony of endangered primates in the world, both in numbers of species and in number of individuals.

John Buettner-Janusch came to Duke University with a collection of over 200 primates in 1966. They settled on 80 acres in Duke Forest, a portion of which Klopfer had already used as a field station for studying/observing maternal behavior in goats. Photo courtesy of Duke University Archives.

Over its history, the DLC has housed, cared for, and made available for non-invasive study nearly 4,000 animals across 31 species of non-human primates including lemurs, lorises, and tarsiers (together, colloquially referred to as prosimian primates). Today, it houses more than 200 individuals across 13 species. The scientific endeavors at the DLC span a remarkable array of disciplines, from behavior and genomics to physiology and paleontology, and the Center is recognized as a global authority on lemur veterinary medicine. Conservation biology is also a major focus, providing the conceptual and operational bridge between the living collections of the DLC and its outreach activities in Madagascar.

A Coquerel’s sifaka in one of the DLC’s signature Natural Habitat Enclosures (NHEs). Here, lemurs free-range in large tracts of forest and live in natural social groups, giving researchers and visitors the opportunity to observe the same behaviors, social structures, and age classes that would be observed in the wild. The NHEs were the brainchild of Peter Klopfer, who advocated for large enclosures (as opposed to the smaller cages then utilized by Buettner-Janusch) so the lemurs could engage in natural behavior.

In 2016, the DLC celebrated a half-century of trail-blazing lemur research and conservation. Much of that knowledge – from research data to ground-breaking insights on health, genomics, paleontology, and more – is showcased here on the DLC website. Take some time to look around. Then, schedule a tour to come and see. Come and see the world’s largest population of lemurs – Earth’s most endangered mammals – outside of Madagascar. Come and see a conspiracy of sifakas leaping through native North Carolina pines. And most of all, come and see what you can do to help the Duke Lemur Center save lemurs from extinction. We can’t do it without you.

Learn More

The Duke Lemur Center's mission is three-fold: to advance science, scholarship, and biological conservation through interdisciplinary non-invasive research, community-based conservation, and public outreach and education. By engaging scientists, students, and the public in new discoveries and global awareness, the DLC promotes a deeper appreciation of biodiversity and an understanding of the power of scientific discovery.

Want to learn more? The "Why" Issue of our official magazine addresses the core mission of the Lemur Center: why do we do what we do? Featuring articles from DLC staff, interns, and collaborators, as well as gorgeous images from our staff volunteer photographers, this issue is infused with the curiosity, beauty, and tenacity that define the DLC! The entire issue can be read free online.

Curiosity and knowledge prompt discovery. Discovery prompts action. And the more we learn about lemurs, the better we are able to protect them in the wild, care for them in captivity, and engage the public to not only care, but to participate. And how do we discover? Through research!

Today, the DLC is home to nocturnal, diurnal, and cathemeral lemurs as well as species that encompass a wide range of social systems, modes of locomotion, and dietary preferences. Such diversity yields a large and diverse research program, and students and researchers from across campus and around the world travel to the DLC to study topics ranging from brain sciences to biomechanics, One Health disease dynamics, aging, paleontology, genomics, and more.

The one thing that all DLC research has in common is that is non-invasive: we do not allow research that will harm our animals in any way. We're proud to serve as a model institution for conducting high-quality research while prioritizing welfare and well-being of each individual in our care; to this end, the DLC is the only facility in the world that holds accreditation with both the American Zoological Association (AZA) and the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International (AAALAC).

Additional research initiatives include:

Madagascar Research Program: This program spans geographical regions and fields of study, is rooted in cross-disciplinary collaborations with in-country experts, and offers funding and mentorship opportunities for Malagasy students and early-career scientists. In addition, in collaboration with the University of Antananarivo (Madagascar), the DLC recently completed construction of a field station in a private reserve in Anjajavy, Madagascar to increase research infrastructure for use by Malagasy scientists and students. The DLC is sponsoring a Malagasy student’s three-year Ph.D. program already underway at the site, and a 13-year MOU has been established between the DLC, the University of Antananarivo, and the Anjajavy reserve to ensure opportunities for students for years to come.

Veterinary Internship Program: The purpose of this program is to share and expand DLC expertise with veterinarians in Madagascar and to provide an opportunity for international collaboration between Malagasy veterinarians, North Carolina State University veterinary staff and students, and Duke University staff and researchers. The goals are to promote cross-cultural understanding, expand career opportunities for Malagasy veterinarians, and creating lasting impacts on human, animal, and ecosystem health in Madagascar.

Research Library: The Center has digitized and made publicly available the vast stores of biological data housed within its archives, enabling investigators worldwide to explore the biological controls of primate health, fecundity, and longevity. The research department also maintains a large inventory of biological samples that are available for scientific study by qualified researchers or institutions (e.g, research centers or museums).

Virtual Ark: Duke and the Duke Lemur Center are using MorphoSource to build a “virtual ark” of the DLC’s animals, making them available to researchers worldwide in stunning 3-dimensional detail. “By scanning them in the microCT and creating these beautiful 3-D models, we can digitize the specimens and share them online. Instead of being locked in a museum drawer, they’re freely available.”

More than 35 years of conservation experience has taught the DLC that sustainable forest protection in Madagascar is a long-term investment that requires building relationships and earning the trust of the local people. The DLC-SAVA Conservation project relies on a community-based approach to protecting natural forests, using an array of project activities designed to protect the forest and to improve the lives of the Malagasy people.

The DLC also works within a network of other accredited institutions in North America and Madagascar to advance lemur care and welfare, and to develop and adhere to Species Survival Plans (SSPs) that use carefully planned conservation breeding programs to create a “genetic safety net” for rare and endangered lemurs. In partnership with these institutions, we’re helping to ensure “the sustainability of a healthy, genetically diverse, and stable” population of lemurs for the long-term future. We’re proud to have celebrated more than 3,437 births since our founding in 1966.

Learn more about the DLC's in-situ and ex-situ conservation work in Madagascar by visiting the conservation homepage.

A critical part of the DLC's mission is to inspire and train the next generation of scientists and environmental stewards. To do that, we offer as many opportunities as possible for visitors, community members, and students to work side-by-side with the Lemur Center's researchers, science educators, animal care and veterinary staff, and conservationists.

Public Tours: More than 35,000 people visit every year to learn about lemurs, science, and conservation. Revenue generated by our tours, special programs, and workshops helps fund the Education Department and pay for lemur care, housing, veterinary supplies, and conservation programs in Madagascar.

Student Engagement: The DLC is a unique “living laboratory” where students can test their ideas in a controlled setting before taking on the uncertainties of the wild. Students exposed to lemurs as undergrads have gone on to make huge strides in the areas of conservation and research. In our video Me and You and Zoboomafoo, Martin Kratt shares stories of how his experience at the Lemur Center took him from being a Duke undergrad to an Emmy Award winner who’s introduced generations of children to lemurs and wildlife conservation. Alex Dehgan, founder of Conservation X Labs and former Chief Scientist at USAID, is another example. Listen to Alex’s story here.

Mentorship and Education: The DLC's robust internships program introduces students to lemur husbandry, animal welfare, scientific communication, environmental education, fossil collection, and lemur research and data collection. The Director's Fund offers financial support to Duke graduate students pursuing research at the DLC, and classes offered through Duke's Department of Primate Anthropology are hosted onsite and include observations of free-ranging lemurs. The Lemur Center also offers funding and mentorship opportunities exclusively for Malagasy veterinarians, students, and early-career scientists.

Community Involvement: Volunteers are an essential and treasured part of daily operations here at the DLC. In 2023 alone, 126 volunteers logged more than 10,800 volunteer hours! We offer a variety of volunteer opportunities that require different time commitments and focus on different interests, and we enjoy hosting student organizations, scout troops, and community groups for project days during the fall and spring.

There are MANY reasons researching lemurs is important and interesting! Here are some of our favorites:

Lemurs are the most endangered group of mammals on Earth. Although lemurs have thrived for tens of millions of years, human activity has now rendered them the most endangered mammals in the world. The threats facing lemurs include habitat loss and fragmentation, increasingly frequent and extreme weather events, changing landscapes and climate, poaching and hunting. As lemur researchers, we cannot ignore the omnipresent conservation concerns facing the animals we study. Rather, we can use research-based initiatives to develop sustainable solutions that are firmly grounded in team-based and integrative approaches. Which brings us to...

The more we learn about lemurs, the better we can work to save them from extinction. Lemurs are endemic only to Madagascar and so it's essentially a one-shot deal: once they are gone from Madagascar, they are gone from the wild. By studying the variables that most affect their health, reproduction, and social dynamics, we learn how to most effectively focus our conservation efforts. And the more we learn about them, the better we can educate the public around the world about just how amazing these animals are, why they need to be protected, and how each and every one of us can make a difference in their survival.

Lemurs are an extremely diverse taxonomic group. When the ancestors of today’s lemurs serendipitously rafted from mainland Africa to Madagascar some 50 million years ago, they became isolated from the rest of the world. Thus launched one of the greatest natural experiments in primate evolution. Since then, 125 species of lemur (and counting) evolved from these early pioneers in Madagascar, where they developed diverse strategies to cope with challenge and take advantage of opportunity. Studying lemurs, and their unique history in Madagascar, allows us to study the evolutionary, ecological, and anthropogenic processes that can shape biodiversity itself.

Most lemurs live in a female-dominant society, and this is relatively rare in the primate world. Studying female-dominant primates yields interesting comparisons to male-dominant or co-dominant societies, and also makes possible the study of why female dominance evolved and how (for example, changes in hormone levels and external anatomy).

Lemurs are part of our family. As primates, lemurs are our most distant living relatives within our own family tree. Studying lemurs within a comparative context across primates allows us to understand ourselves, and the traits and processes that make us both primate and human. Moreover, we share with lemurs the vast majority of our genetic code and many of the same diseases, susceptibilities, and health concerns. Studying lemurs cold potentially help us find solutions to combat serious problems facing modern society.

The Duke Lemur Center understands and appreciates concern regarding the historical beginnings of our colony; the need for long-term work in Madagascar to ensure scientific, humanitarian, and conservation stewardship; and the importance of serving as a leader in ethical practices of captive primate research centers. We recognize that living lemurs are the natural and cultural heritage of Madagascar, and as an institution based outside Madagascar, we recognize that we have an obligation to give back to conservation and development efforts in Madagascar. Read our full ethics statement.

The Duke Lemur Center is absolutely against all trade in pet primates, and against the holding of any prosimian (lemur, loris, bushbaby, potto) as a pet.

Much has been written about the serious, negative impact of the pet trade on the conservation of lemurs throughout Madagascar. Our article "Pet Lemurs: The Pet to Regret" addresses a related, but different, issue—one that’s even closer to home: the pet lemur trade right here in the United States.

To learn more, please read the DLC’s formal position statement on pet lemurs.

Support the DLC

Your support makes so much possible! The DLC relies on gifts from businesses and individuals like you to invest in our work to learn from and protect lemurs and their natural habitat in Madagascar. Your support fuels our impact through conservation, education, and non-invasive research programs.

The Duke Lemur Center operates under Duke University and meets the requirements of the Internal Revenue Code Section 501(C)(3). Gifts to the DLC are deductible at the highest limits allowed for federal income or estate tax purposes. Tax receipts will come from Duke University, Federal Tax ID 56-0532129.