By Andrea Tejada, 2022 Communications Intern

Illustrations by Karie Whitman

Click here or on the image above to read the full article with photos and illustrations.

Originally published in January 2023 in “The Women’s Issue” of the DLC annual magazine.

Mapping Herstory: Studies in Female Dominance

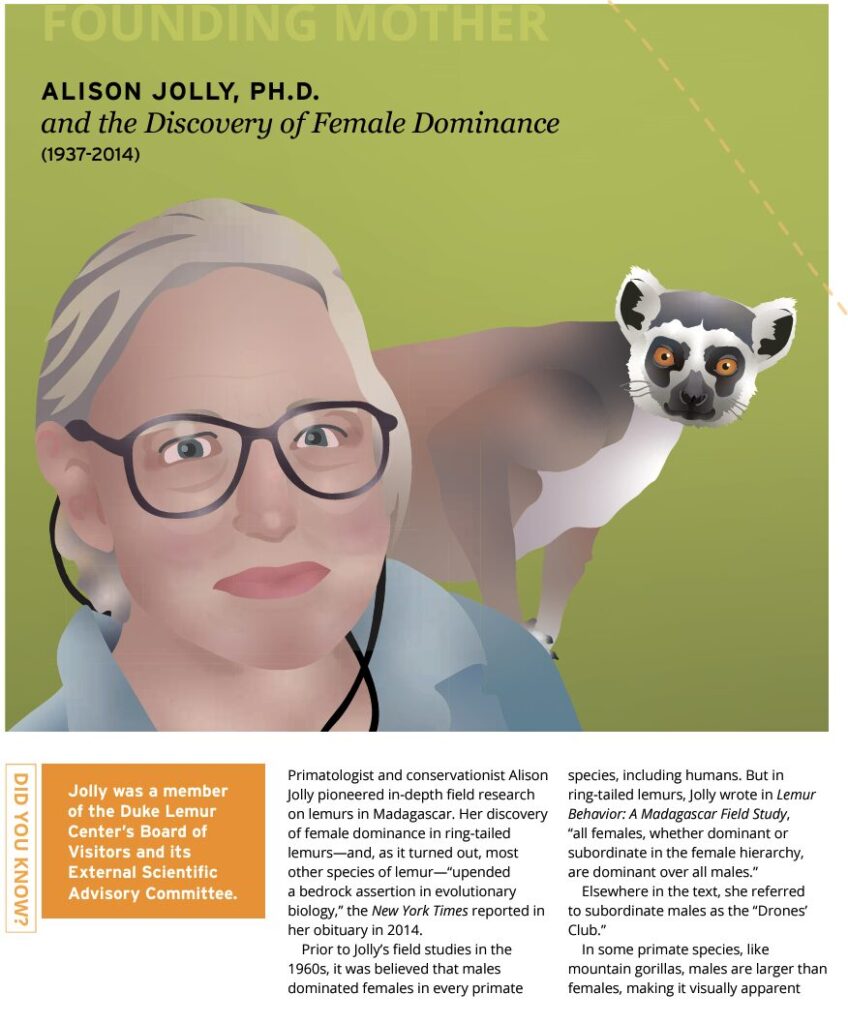

Since its inception, the field of primatology has been dominated by star-studded cast of influential women, from ape researchers Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey to the lemur-loving Alison Jolly, Patricia Wright, and Dame Alison Richard.

Likewise, the non-human constituents of the primate order are notable for their instances of female dominance. Although many primates, including Goodall’s chimps and Fossey’s mountain gorillas, exhibit male-dominant social structures, female dominance is encountered in nearly all prosimians—the suborder that includes lemurs, lorises, pottos, bush babies, and tarsiers and comprises more than 20% of all primate species.

In nearly all of the 108 species of lemur, females are the respected royalty. One wrong look given by a male lemur to a female could provoke a smack, hair pull, or atail yank. And it’s not just the most dominant female who holds the power: Any female within the troop, even juveniles, can outrank any male—including the breeding (dominant) male.

Fittingly, the staff at the Duke Lemur Center is overwhelmingly comprised of women. In 2015, women held only 28% of all science and engineering jobs, but at the DLC, more than 80% of staff identify as women.

Research has shown that girls tend to lose interest in STEM-related careers around age 15 for reasons that include social pressure, lack of female role models, and an overall misconception of what “real world” STEM careers can look like. My goal in sharing the stories of the DLC’s strong and successful women is not just to spotlight them and their achievements, but also to inspire and encourage others to follow their dreams with fearlessness and tenacity.

The advice given to me most often by these women was that there is no one “right” way to end up in a career you love. Learning to accept that you may not know in advance the trajectory your career path will take, has been a common theme in many of these journeys. I hope that by sharing these stories we can empower other women in the exploration and pursuit of their passions.

Erin Ehmke, Ph.D.

Director of Research

“When I was younger, I didn’t really know how to pursue a career with animals,” Erin recalls. “I thought the only two paths were veterinarian and zookeeper.

After graduating high school, Erin opted to pursue becoming a veterinarian—and quickly realized that a pre-vet focus just wasn’t for her. She volunteered in a lab for a professor studying Old World monkeys, helping analyze fecal samples for intestinal parasites. This was Erin’s introduction to research, and it helped her see a clearer path toward her career goal.

Ultimately, it was her experience at a primate sanctuary that solidified Erin’s path. After years of working at a sanctuary that rescues abused or unwanted monkeys from the pet and entertainment industries, “I was craving to learn how different these monkeys’ behavior was from their wild counterparts’,” says Erin. “It was then that I realized: I was ready for my Jane Goodall moment.”

Through her varied experiences, “I had learned about opportunities that I never knew existed that could make that dream possible,” Erin recalls. After attending a month-long primate ecology field school in Panama, she became a field assistant for an ongoing study in Suriname. “That position focused on capuchin monkey behavioral ecology and gave me the opportunity to do what I craved: to experience the natural lives of the monkeys I had worked with in captivity.

“That year was one of the best of my life. Afterward, I enrolled in a Ph.D. program in Biological Anthropology and returned to Suriname for additional fieldwork. I studied female support and stress in wild capuchin monkeys, learning just how important social bonds are for the health of primates—humans included.”

Today, Erin’s favorite part of working at the DLC is her ability to combine all of her career interests into one role. “When I was teaching after graduate school, I loved it, but I missed working with primates and the excitement of asking scientific questions and collecting data to answer them.”

In her role as Director of Research, Erin combines her passion for student mentorship with the non-invasive study of lemurs. “My vision is to expand our research programs in both Durham and Madagascar, serving as a model institution that prioritizes animal welfare, high-impact research, and access to opportunities for all students and scientists.

“When I was younger, I dreamed of this path but I didn’t know how to achieve it—partly because I didn’t realize the breadth of opportunities that were out there. I encourage all students, of any age, to try new experiences. And I make it my personal mission to make opportunities accessible for students trying to find their own paths.”

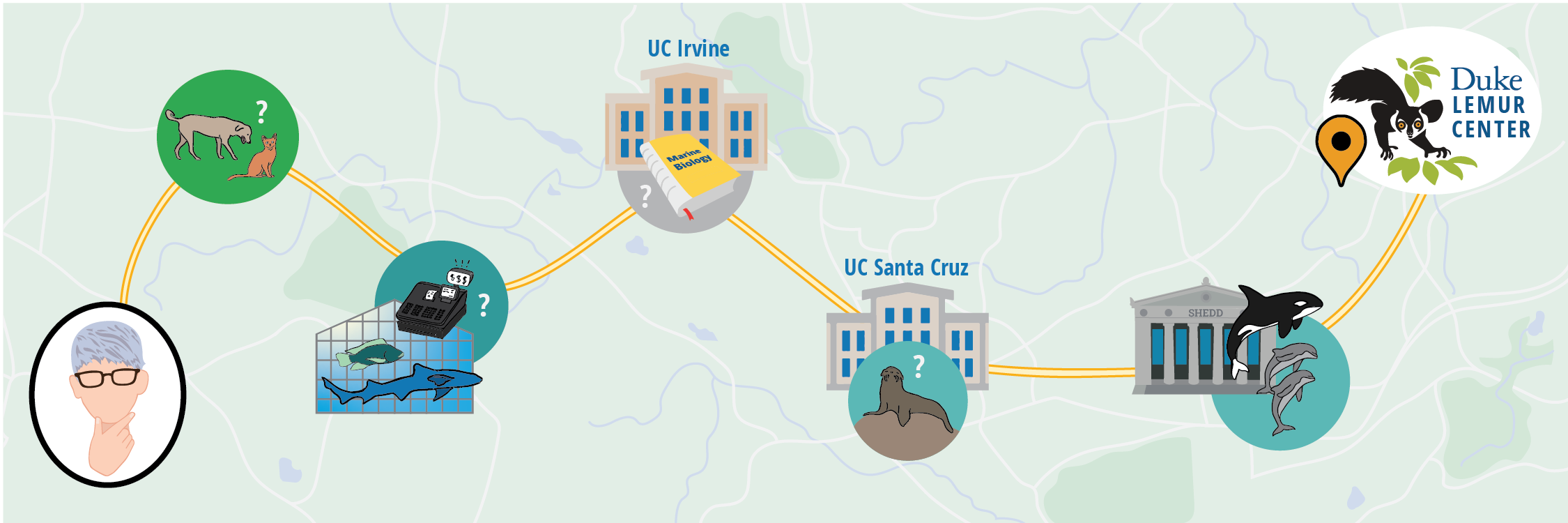

Meg Dye, M.Sc.

Curator of Behavioral Management and Welfare

“I’ve always wanted to do something with animals,” says Meg, “but as a kid, I wasn’t sure what that would entail.” When the Monterey Bay Aquarium opened nearby, Meg was in high school and was hired as a cashier. “I learned I did not want to be a cashier,” she laughs, “but the aquarium was fascinating.”

When she enrolled at the University of California, Irvine, Meg didn’t have a solid plan yet for her future. She became increasingly interested in marine biology and, after two years at UC Irvine, transferred to the University of California, Santa Cruz. She’d been drawn to UCSC’s Joseph M. Long Marine Laboratory, a facility for non-invasive research much like the Duke Lemur Center. “That’s where everything clicked,” Meg says.

At the Long Marine Lab, Meg learned the principles of positive reinforcement training through her involvement with a sea lion cognition project. “I was introduced to training and given hands-on experience working with marine mammals, and the rest is history!”

After graduation, Meg worked for ten years as a lead dolphin trainer at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago, then launched a consulting business specializing in positive reinforcement training in zoos. At the same time, the Duke Lemur Center launched a training program to complement its husbandry and non-invasive research projects. The DLC’s Director, Anne Yoder, hired Meg as a consultant for five years, then as a full-time staff member in 2011.

Today Meg holds a master’s degree in Animal Welfare, Ethics, and Law and oversees the DLC’s behavioral management program. In doing so, she collaborates across departments to promote positive animal welfare—a top organizational priority of the DLC, and a key component of the highest quality lemur care.

Karie Whitman

Fossil Preparator

“There’s no degree for this job. It just kind of happened,” laughs Karie, who began her undergraduate education on a pre-med track, which required employment in a campus laboratory. After interviewing for numerous positions, she was hired by a fossil lab to make casts of whale bones—a chance job that served unexpectedly as the foundation for her career.

After graduating from the University of Michigan with a B.S. in Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, Karie traveled to the Buckeye State to pursue a master’s degree in Environmental Studies at Ohio University. For her master’s thesis, she worked in Madagascar studying rice agriculture, collaborating with the Peace Corps on educating local communities about sustainable and efficient farming techniques. After publishing her thesis, Karie received a Fulbright grant to continue her research and outreach to local Malagasy farming populations.

After returning from Madagascar, Karie received a call from Dr. Matt Borths, Curator of Fossils at the DLC Museum of Natural History. He and Karie had met in OU’s fossil lab, and he invited her to apply for an opening for a fossil preparator at the DLC. She was hired in 2020.

Today, working at the Lemur Center enables Karie to embrace additional roles such as designing exhibits for the fossil museum and infographics for educational projects, including illustrations featured in this article; as well as maintaining contact with partner individuals and organizations in Madagascar. “One thing that always comes up with my career journey is that you can do lots of things at once,” says Karie—and that suits her perfectly.

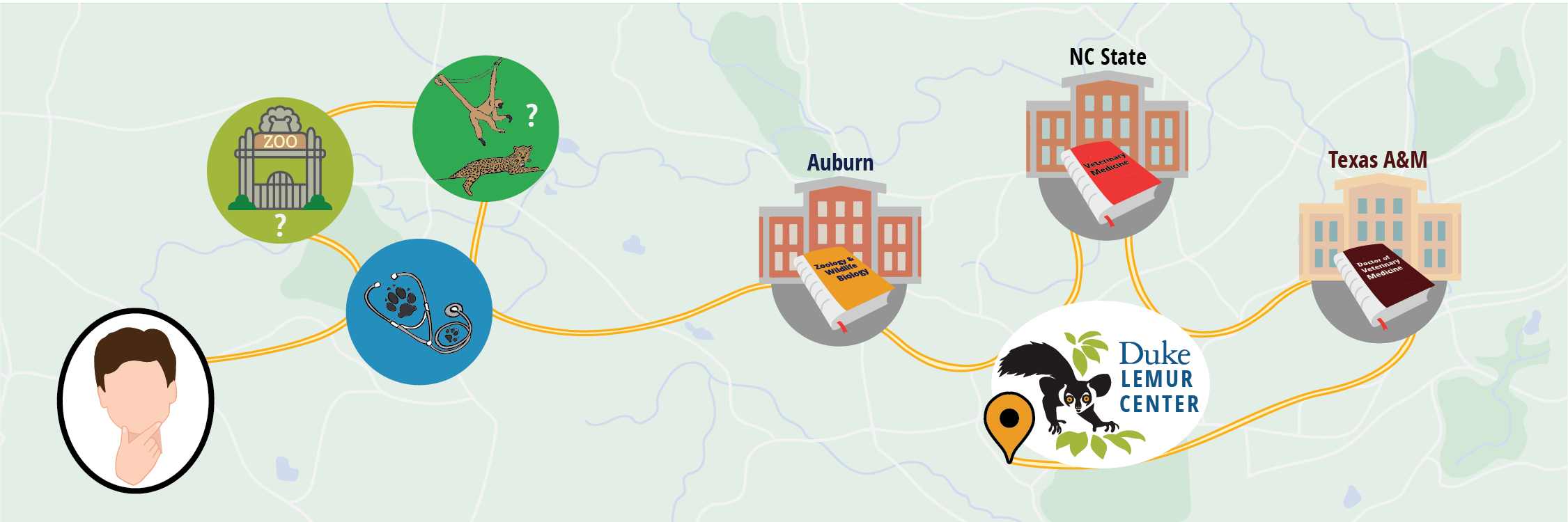

Laura Ellsaesser, D.V.M.

Veterinarian

“I’ve always been drawn to zoos, wildlife, and conservation,” says Laura. “I knew from a young age that I wanted to be a veterinarian.” She tailored her education in pursuit of that goal, graduating from Auburn University with a B.S. in Zoology and Wildlife Biology and accepting a husbandry internship with the Lemur Conservation Foundation.

“In Florida, I became fascinated with lemurs and developed a soft spot for mongoose lemurs in particular,” she recalls. “When I started vet school at North Carolina State University, I knew the DLC was just down the road. Initially I hoped to volunteer, but a busy school schedule didn’t permit that, so I took advantage of every class and rotation that brought NCSU students to the Lemur Center.”

In doing so, Laura developed a strong professional relationship with DLC veterinarian Bobby Schopler, D.V.M., Ph.D., who encouraged her to stay involved at the Lemur Center even after completing her degree.

After earning her D.V.M. at Texas A&M University, Laura completed a year-long internship in small animal medicine and surgery. While there, she worked closely with a nearby zoo, indulging her interest in wild animals while honing her skills in dog and cat medicine and surgery.

Her next position, as a small animal ER doctor in Virginia, not only brought her closer to home but also had a highly appealing schedule. “I had every third week off,” says Laura. “What better way to spend that week than by driving to the Triangle to visit friends and spending time with the veterinary department at the DLC?” The DLC’s veterinary team welcomed these trips and invited Laura to assist whenever she was available.

Two years later, she received a call from Bobby. “He told me the staff veterinarian position was opening up at the DLC,” Laura remembers. “I was floored. He had invited me to apply for my dream job. This is the stuff that happens in the movies. It was unbelievable.”

After a three-month application and interview process, Laura’s dream came true. She’s been with the DLC for five years, and “I couldn’t be happier!”

Even though she knew early on that dog and cat medicine wasn’t for her, Laura values the jobs and internships she held before coming to the DLC, as those positions gave her the opportunity to practice clinical skills that are all applicable to lemur health and care. There is no handbook for lemur veterinary medicine, and the Lemur Center’s veterinarians draw upon their experience with domestic animals while working closely with husbandry staff, researchers, and small animal specialists to determine the best courses of action for many of the more challenging lemur health issues.

That challenge is part of the appeal for Laura, and she’s happy to be working in such a collaborative environment. Her advice for people interested in non-traditional career paths? “There’s no one way to do it, and that can be really intimidating. Just dive in and chase anything that’s interesting to you, and see what sticks!”

Sara Sorraia

Director of Communications

Sara is the daughter of a seventh-generation farmer, an all-around farm kid hailing from the Appalachian foothills of southern Ohio. Her parents’ neighbors are Amish. “If you’d told 12-year-old me that someday I’d be a communications director at a globally-ranked university just outside the ‘Silicon Valley of the East,’ I wouldn’t have believed you,” she laughs.

She started taking college classes after her sophomore year of high school: They were free, thanks to an agreement with the local schools—and finances were a big factor for the family. She banked all the credits she could and, later, finished her BA in a swift three years, concentrating in the eminently practical field of… classics. “I couldn’t help it,” says Sara. “I like my artwork ancient and my languages dead.”

At the time, she wanted to be a professor. But she was painfully shy, and she knew she couldn’t lecture in front of a class. Before pursuing graduate school, “I decided to look for a job that would force me to talk to strangers. I opened the classifieds and a local Nissan dealership was hiring salespeople. I applied and surprise! I was hired.”

She sold Nissan cars and trucks for three years. That experience—sales, negotiation, customer service, even repping Nissan at auto shows—was invaluable. She didn’t know it then, but it would form the foundation of her future career.

Sara enrolled in graduate school at Duke in 2007. she jokes. “Around the same time, my parents put our land in a conservation program and planted 17,000 trees in former cattle fields. My brother began transitioning to organic farming, and Dad became interested in bobwhite quail conservation. I began to understand more deeply the importance of caring for the land and the wild creatures it supports.”

After graduating from Duke (where her thesis focused on the “language” of art in the Middle Ages), Sara co-managed an undergraduate admissions department before accepting a position in sales, marketing, and editorial development at Oxford University Press. Later, she managed tours, visitor relations, and special events at Duke University Chapel for four years before joining the DLC in 2016.

“My professional background grew into a blend of sales and marketing and interfacing with the public, which transitioned perfectly into my ‘dream job’ here at the Lemur Center,” says Sara. “Now, for the first time in my life, I’m working at a job that unifies the two worlds that I live in and love—professional and personal. Not only am I back around animals, but I get to use the skills I’ve developed over the past 16 years to help spread the word about lemurs.”

Her advice? “Be insatiably curious. Ask questions. I heard once that in every interaction, you’re there either to learn or to teach. Sometimes both, of course; but wherever you are, always think about the things you can learn. Those experiences can have surprising impacts on your future career.”

Amanda Mazza

Data Manager and Registrar

Amanda Mazza originally set out to pursue a career as an animal rights lawyer. But jobs in that field were scarce, and no other field of law interested her; so Amanda, ever practical, explored other options.

Although intrigued by primatology, evolution, and biology, Amanda struggled with math, and teachers and counselors discouraged her from pursuing a career in STEM. “Even though I fully believed I’d never have a job in this field, I was still passionate about it,” she recalls. Nevertheless, she strayed from the sciences and earned a bachelor’s degree in history.

After several long years as a substitute teacher, Amanda obtained a position in public health, later earning a Master of Public Health from West Chester University’s College of Health Sciences. By that time, Amanda was working full-time running a program that provided assistance to those with HIV—a program she describes as her “biggest achievement in public health.”

A major component of that position was data management, and Amanda realized she wasn’t as bad at math as her advisors had convinced her she was. She used math and statistics daily; it was just presented in a way that was easier for her to understand. After a promotion to a supervisory role, Amanda missed the data management aspect of her work, and an opening for Data Manager and Registrar at the DLC caught her attention.

Amanda has now been with the DLC for three years, working with all departments to create databases that store a wide variety of information on all the prosimians housed at the Lemur Center, and striving constantly to devise new ways to organize the data. “Looking back, it makes sense that all the skills that I developed in public health were applicable here.

Megan McGrath

Education Programs Manager

The one thing Megan knew she didn’t want to be when she grew up? A teacher. “The irony is not lost on me,” says Megan. “I thought of education as a narrow, specific field—a teacher in a classroom, as opposed to the exciting, informal education we do at the DLC.”

A driven and motivated kid, Megan was always interested in animals. “I was christened ‘The Encyclopedia of Useless Animal Information’ by one of my good friends,” she laughs. Yet she never connected her love of animals to the field of science. “To me, science was just microbiology and looking through a microscope.”

As an undergrad, Megan opted to study Psychology and International Studies. After finishing an independent research study her senior year, she discovered to her dismay that she didn’t enjoy the process of research—upending her dreams of an eventual Ph.D. in Psych. “It was a real blow to realize that what I thought I was going to do, I didn’t like. I felt like a failure.”

That same year, Megan had accepted an animal care internship at the Conservators Center, a nonprofit wildlife education center focused on large carnivores such as lions, tigers, and wolves. “It became increasingly clear to me how invested I was in my unpaid internship versus the research I was supposed to be doing in psychology,” she recalls.

In retrospect, Megan says, “I wasn’t a failure; psychology was just the wrong path for me. It’s okay to acknowledge when something you thought you wanted, something you’ve worked toward, just doesn’t feel right.

“I had no idea how heavily my own expectations had been weighing on me. It took a long time to let them go, but once I did, I felt an immediate release. I could move on.”

Megan didn’t apply to Ph.D. programs. Instead, after graduation, she juggled three animal-related, part-time positions: animal care at the Conservators Center, pet sitting, and front-desk assistance at a veterinary office. “It was tough, but it allowed me to explore my career interests until I could find something full-time,” she says. “I was fortunate to have supportive parents.”

Ultimately Megan progressed from keeper to tour guide to Education Programs Supervisor, overseeing all tours and special events at the Conservators Center. She joined the Lemur Center in 2016 after the DLC’s then-Education Manager, who was moving into a new role, notified her of the opening and encouraged her to apply.

“Treat every interaction as a job interview,” says Megan. “If I hadn’t met the previous manager through environmental education events, I never would’ve applied for this position. This is a small field, and we want to see each other succeed. We’re all happy to recommend wonderful people we’ve worked with as candidates for great roles.”

Primatology’s Founding Mothers

In addition to DLC staff, Andrea’s article highlights four “founding mothers” of primatology: Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, Birute Galdikas, and Alison Jolly. Click here to view the full article, including profiles and illustrations of these four influential researchers.