Slow Loris

Deep in the jungles of Southeast Asia, a venomous creature stalks the night… very, very slowly. So slowly, in fact, that it has become part of their common name in English: the slow loris. While the slow loris now lives across a few oceans and continents from its relative, the lemur, these early primates share a branch of the primate family tree with not only its Madagascar cousins but also the bush baby, found on Mainland Africa. How did they end up all the way in Asia? Well – very, very slowly.

A slow loris stares down the camera, showing off its tongue and toothcomb.

The earliest fossil evidence for strepsirrhine primates (the earliest branch of the primate order) estimates these early lemur and loris relatives appearing around 60 million years ago. Strepsirrhine means curled nose, which among other features distinguishes the early primates from their successors, the haplorrhines. Strepsirrhines include lemurs, lorises, and bush babies. 60 million years ago, these strepsirrhine primate “prototypes” would have looked very different than they do today – but then, so did the continents. As the continents shifted, connected, and disconnected, primates were able to migrate all across the world over millions of years. The result is that the lemur family today is found only on the island of Madagascar, while bush babies and some members of the loris family remained on mainland Africa, and other loris groups are now in Southeast Asia.

There are nine species of slow loris (genus Nycticebus) and two species of slender loris (genus Loris). Graphic by Peppermint Narwhal.

While the loris family is still relatively understudied, four geni are generally recognized: the slow loris (genus Nycticebus) and slender loris (genus Loris) of Southeast Asia, and the potto (genus Perodicticus) and angwantibo (genus Arctocebus) of Africa. All loris species rely on undisturbed rainforest for their habitat. While neither slow nor slender lorises are built for speed, the primary difference in their body type is the length of the limbs. The slender loris has long, slender limbs and a more pointed face, and is able to move more quickly than the slow loris. All slow loris species are tailless or short-tailed. The index finger of the hand is shortened, and both hands and feet have extreme grasping ability, allowing lorises to hang from a single hand or foot for extended periods of time.

A slender loris explores its habitat at the DLC.

Since slow lorises are nocturnal, they have large eyes which are adapted for better light absorption. Though lorises do not live in social groups like diurnal primates, they are known to interact frequently with conspecifics in their overlapping home ranges, and to engage in typical social behaviors such as grooming.

Lorises will bear one to two young per year, which the mother will intermittently “park” in the trees and allow to cling under her belly to ride along. The slow and quiet locomotion of the loris family coupled with an ability to remain perfectly still for long periods of time produce a highly effective cryptic locomotion style, which makes them appear to be no more than a leaf rustling in the breeze to potential predators. While this cryptic locomotion is the primary means of predator defense, slow lorises have a trick up their sleeve: a toxic saliva produced by combining secretions from their brachial (arm) glands with saliva. Lorises will typically raise the arms over the head preceding attack.

While lorises remain cryptically hidden in the rainforests, their populations are declining, and all species are currently considered endangered. The primary threat to slow lorises is habitat destruction and degradation, due to agriculture and development. However, lorises also face a direct threat of capture for wildlife trade – for use in traditional medicine, as bushmeat, or as illegal pets. It is not uncommon to find lorises used as props for tourist photos or being sold in the markets as pets – typically with their teeth having been removed, for the safety of the paying customers. Photos and videos of these large-eyed primates being petted, hand-fed, or tickled (responding with their defensive arm-raising behavior) can easily promote the idea that lorises make good pets, contributing to an international trade which directly impacts wild populations and individual lives.

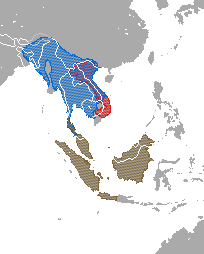

Geographic range and distribution of the slow loris (genus Nycticebus) through southeast Asia. Red= N.pygmaeus. Blue= N. benegalensis. Brown= N. banacans, N. borneanus, N. coucang, N. javanicus, N. kylan, N. menagensis.

While efforts to liberate and rehabilitate captured lorises are ongoing, captive-born loris populations in animal care facilities around the world are also part of a Species Survival Plan to contribute to slow loris conservation. Like so many of their primate relatives, slow lorises are an important chapter in evolutionary history, and a precious resource we cannot afford to lose.

To learn even more about lorises, check out our sources below:

Fleagle, J.G. (2017). Plate Tectonics and Continental Drift. In The International Encyclopedia of Primatology (eds M. Bezanson, K.C. MacKinnon, E. Riley, C.J. Campbell, K.(. Nekaris, A. Estrada, A.F. Di Fiore, S. Ross, L.E. Jones‐Engel, B. Thierry, R.W. Sussman, C. Sanz, J. Loudon, S. Elton and A. Fuentes). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119179313.wbprim0247

K. A. I. Nekaris, Anne M. Burrows

Evolution, Ecology and Conservation of Lorises and Pottos’

Cambridge University Press, Mar 19, 2020 – Nature

https://www.iucnredlist.org/species/163017685/17970966