History of the DLC

Imagine going to a university for four years and finding out that the entire time there were more than 200 lemurs living just down the road. While it may seem surprising that a population of energetic, vocal, and occasionally odiferous primates could escape the notice of a generation or two of students, many alumni visiting the Duke Lemur Center for the first time had never heard of it while they were attending Duke decades ago.

Despite winning the Indy Week’s Best Kept Secret award in 2018, the Duke Lemur Center (DLC) is more well-known than ever, attracting visitors and researchers from around the world to come and experience the 200-plus lemurs that live here in the Duke Forest. But many people don’t realize just how long the DLC has been around, and how much it has changed over the past 54 years.

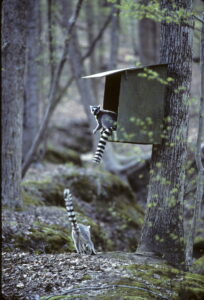

Ring-tailed lemurs “free-roaming” in the natural habitat enclosures at the DLC.

In 1966, the land that is currently home to free-ranging lemurs was inhabited instead by populations of goats, European fallow deer, screech owls, and ducks, which were the subjects of some of the biological research conducted at Duke University. One such Duke biologist, Dr. Peter Klopfer, was studying maternal behavior in these very un-lemur-like animals at the time, but a newcomer to Duke’s campus would soon shift his focus to the primate world. Dr. John Buettner-Janusch was a Yale professor studying biochemical genetics in lemurs. This somewhat unprecedented research was made possible through a population of about 90 prosimian primates, which he relocated to Durham when he was offered a position at Duke. That Duke Forest land and facilities would now be populated with lemurs and their close relatives, including tarsiers and bush babies. With the partnership of Dr. Klopfer and grant money from the National Science Foundation, the Duke University Primate Center (DUPC) was born–a non-invasive research facility focusing on prosimian primates.

Lemur enclosures in the early days of the DLC

Even from the beginning, the Duke Lemur Center (then DUPC) has been the largest and most diverse collection of prosimian primates in the world. But the collection has looked quite different over the years as we have learned more about lemur behavior, husbandry, and genetics. In total, approximately 4,000 individuals representing 31 different species have called the Duke Lemur Center home since 1966. Currently, the DLC houses about 210 individuals representing 15 species of prosimian (one non-lemur species included). Over 50 acres of the Duke Forest are dedicated free-range habitat areas, and in 2010 new animal housing buildings were constructed, providing better winter accommodations for these tropical primates.

An original bamboo lemur enclosures at the DLC

Construction of two new, substantially improved indoor lemur habitats broke ground in 2010.

While the DLC has always primarily operated as a center for non-invasive research, it became clear in the 1970s that lemurs were in trouble, and the aging population of lemurs at the DLC was not an adequate genetic safety net for their endangered counterparts in Madagascar. In 1977, renowned primate paleontologist Elwyn Simons became the director of the Duke Lemur Center, and with special permission from the Malagasy government, was able to conduct missions to Madagascar to bring wild-caught lemurs back to the United States to join the lemur population at Duke. These carefully-selected missions enabled new genes to be introduced to the DLC, creating a healthy gene pool of certain species through which the survival of lemurs outside of Madagascar might be secured. In the 1990’s Simons and colleagues were able to begin a process of reintroduction of lemurs to Madagascar which would continue till 2001.

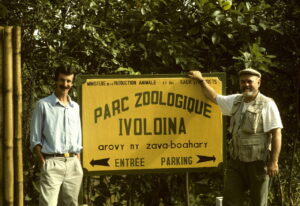

Charlie Welch and Elwyn Simons in front of the sign to Parc Ivoloina in Madagascar.

Elwyn Simons remained director of the Duke Lemur Center until 1992. In addition to his vision for the conservation of living lemurs, he was a famed paleontologist and during his tenure, the DLC became home to some of the rarest early primate fossils ever discovered. The DLC Museum of Natural History (formerly the Division of Fossil Primates), now curated by Matt Borths, is home to over 35,000 fossil specimens of early primates and their non-primate counterparts. This critical collection helps researchers begin to understand the origins of the primate family, and what life might have looked like when the earliest lemur ancestors were walking (or bouncing!) on earth.

Elwyn Simons (left) and Prithijit Chatrath at the DLC Division of Fossil Primates.

As the population of lemurs in Durham grew and diversified, the DLC became more directly involved with lemur conservation in Madagascar, and through the efforts of Charlie Welch and Andrea Katz, succeeded in reintroducing the first five of 13 black-and-white ruffed lemurs to Madagascar in 1997. In 2012, the SAVA Conservation program began as an independent initiative supported by the DLC, which would enable greater focus on community conservation efforts in the SAVA region in northeastern Madagascar. Now led by Charlie Welch, James Herrera and Lanto Andrianandrasana, the SAVA program is supported entirely by grants and donations.

Guests engage with Charlie Welch (far right) and Andrea Katz (second from left) in 2019 at the DLC’s Mission: Madagascar fundraising event to support DLC conservation programs in Madagascar.

Today, the Duke Lemur Center is still making strides in research and conservation, working to protect lemurs in Madagascar, and helping to spread the word about our endangered primate ancestors across the world. The DLC is an ever-changing landscape of forest, natural habitat enclosures and animal care buildings – soon to include a brand-new research building and veterinary hospital, thanks to the support of a generous donor. In the early days of a more hidden, exclusive research facility, you would not have seen colorful lemur footprints leading families toward the tour path, or signs along the fences reminding guests that these cute animals are still wild, so hands off! A great deal has changed, but the mission remains the same: to discover all we can about these endangered primates, to engage the public to learn and care about them, and to protect lemurs in their natural habitat.

A female collared lemur with her two infants in the early decades of the DLC.

It is not uncommon to hear returning Duke Alumni describe their experiences working or studying at the Duke Lemur Center, back before it was well-known or even open for tours. Many other Alumni reflect on their surprise that the Duke Lemur Center exists at all, and is not only open for visitors, but hosts over 35,000 visitors per year! After more than 50 years of lemur research, 35 years of conservation, 4,000 students, and 1,000 publications, we are certainly glad that the secret is out!