Creature Feature: Sifakas

Gabe, a young male sifaka enjoys a leafy snack in the DLC’s forest enclosures. Photo by Bob Karp.

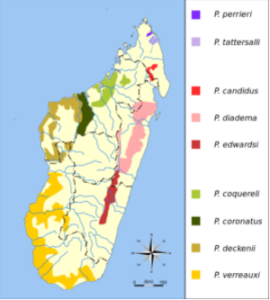

In a group of nearly one hundred incredibly unique, diverse, and specialized animals, it might seem hard to stand out. The lemur family includes a wide variety of shapes, sizes, colors, dietary preferences, and modes of locomotion, all of which are fascinating and meaningful to the scientific community. One of the more well-known species of lemur is the Coquerel’s sifaka, made famous by the Kratt Brothers in the PBS show Zoboomafoo. Coquerel’s sifakas are certainly the most well-known of their genus, but there are nine known species of sifaka (or members of the Propithecus genus) currently living in Madagascar. The other eight species are the Verreaux’s sifaka, the Milne-Edwards sifaka, the Perrier’s sifaka, the Silky sifaka, the diademed sifaka, the crowned sifaka, the golden-crowned sifaka, and the Van de Decken sifaka. While all of these sifaka species have their own unique home ranges, colorations, diets, and social behaviors, they all share some key characteristics.

Sifakas are named for a vocalization they make, which sounds like “shee-fauk!” or a camera shutter. All sifakas are easily recognizable by their morphology and locomotion style—a vertical posture and long back legs allow them to cling and leap through the trees, sometimes at horizontal distances of up to thirty feet. But the real sifaka claim to fame is the bipedal hopping movement they use on the ground. Holding their arms out for balance, sifakas will bounce, skip, and gallop along the ground on their back legs, earning them the nickname “the dancing lemurs.” This locomotion style is not only unique in the primate world, but in the mammal world as well!

A family of Coquerel’s sifakas leap through their forest enclosure.

This vertical clinging and leaping locomotion is a key feature in the Propithecus genus as well as their near cousins in the Indriidae family, the indri and the woolly lemurs. However, it is unclear how far back this particular locomotion style goes in lemur evolutionary history. The closest sub-fossil relatives of the Indriidae family were likely the sloth lemurs, which may have lived in Madagascar as recently as 500 years ago. Some of these extinct sloth lemurs, like Palaeopropithecus, were probably about three times the size of the sifakas now living in Madagascar, weighing around seventy to eighty pounds on average. Though it may be exciting to imagine such a large lemur leaping and bounding across the prehistoric landscape, the anatomy of Palaeopropithecus is better suited for slow, upside-down climbing through the trees (hence the moniker “sloth lemurs”). Sifakas still practice this sloth-like hanging while they forage for food, but their smaller body size has allowed for faster movement through the trees. Despite their difference in size and locomotion style, the anatomy and dentition of Palaeopropithecus indicates that they probably ate the same kinds of leafy things that their descendants do today.

Palaeopropithecus, an extinct “sloth” lemur, had curved fingers and toes to assist in upside down suspension.

Sifakas are generally frugo-folivores, meaning that they eat both fruit and leaves. This dietary designation also encompasses things like nuts, seeds, bark, fungi, and even soil. The specific types of plants that each sifaka species eats and how they go about foraging for them is different depending on what area of Madagascar they inhabit. The nine species of sifaka are distributed in both the eastern rainforests and western deciduous forests of Madagascar, as well as the southern spiny desert. These three habitat ranges come with their own sets of challenges and benefits—weather events, seasonal changes, not to mention spiny trees can all play a role in how sifaka forage and what plants they consume. The Coquerel’s sifakas are found in the western deciduous forest, where they eat a diet heavy in leaves.

A map of Madagascar highlighting the different ranges of the nine different species of sifaka. Source: IUCN Red List 2012.

While the diets may be variable, sifakas do share another unique characteristic among lemurs: their gut. A diet heavy in fibrous, cellulose-rich leaves requires lots of processing time, so the sifaka digestive system is about three times the length of most other lemurs, and about 14 times the length of their own bodies. The length of the digestive tract allows sifaka to extract all of the nutrients out of the leaves, a process which takes upwards of twenty-four hours to complete. This amazing adaptation serves sifaka well in the wild, but can make them vulnerable to gastrointestinal diseases when in human care or in fragmented ecosystems.

Left: Calpurnia munches on kale from her breakfast bowl. Right: A diagram by Erin McKenney of the long digestive tract that helps her process her kale.

As arboreal, leaf-eating animals, sifaka are reliant on primary forest to thrive. Unfortunately, deforestation and habitat fragmentation are causing sifaka populations to decrease. All nine species of sifaka are currently listed as critically endangered, but efforts to protect them and their habitats are in full force. Conservation breeding programs, reforestation, land preservation, and environmental education are all at work to maintain and build the populations of these incredible species, and there has already been success in building populations back up in the wild and in human care.

Alfieri, F., Nyakatura, J.A. and Amson, E. (2021), Evolution of bone cortical compactness in slow arboreal mammals. Evolution, 75: 542-554.

Godfrey, L.R. (2017). Subfossil Lemurs. In The International Encyclopedia of Primatology (eds M. Bezanson, K.C. MacKinnon, E. Riley, C.J. Campbell, K.(. Nekaris, A. Estrada, A.F. Di Fiore, S. Ross, L.E. Jones‐Engel, B. Thierry, R.W. Sussman, C. Sanz, J. Loudon, S. Elton and A. Fuentes).

Shapiro, L.J., Seiffert, C.V., Godfrey, L.R., Jungers, W.L., Simons, E.L. and Randria, G.F. (2005), Morphometric analysis of lumbar vertebrae in extinct Malagasy strepsirrhines. Am. J. Phys. Anthropol., 128: 823-839.

Godfrey, L.R. and Jungers, W.L. (2003), The extinct sloth lemurs of Madagascar. Evol. Anthropol., 12: 252-263.

Comparative Analysis of the Gut Microbiome in Lemurs (Order: Primates)McKenney, Erin Alison.Duke University, ProQuest Dissertations Publishing, 2017. 10257778.

Sato et al. 2016. Dietary Flexibility and Feeding Strategies of Eulemur: A Comparison with Propithecus. International Journal of Primatology. 37: 109-129.

Campbell et al. 2000. Description of the gastrointestinal tract of five lemurspecies: Propithecus tattersalli, Propithecus verreauxi coquereli, Varecia variegata, Hapalemur griseus, and Lemur catta. American Journal of Primatology. 52: 133-142.