A Look into the Illegal Wildlife Trade

Rosewood furniture, ivory pianos, crocodile handbags, and tiger-skin rugs may sound like the fashion ideal of a wealthy movie villain, but the ongoing trade of illegal wildlife for products like these is a harsh reality. The illegal sale of wildlife and wildlife products is one of the most lucrative businesses in the world, with over $10 billion in smuggled goods being traded and bought every year. While some wildlife trade is perfectly legal and even sustainable, the poaching and selling of endangered animals, plants, corals, and other protected organisms is a huge conservation concern. Conservationists are working hard to find new ways to track and protect these endangered species, and put a stop to harmful poaching and trading practices.

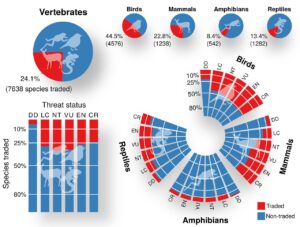

This graphic from Scheefers et al shows the span of wildlife trade across vertebrate species.

Much of the demand for illegal wildlife trade comes from the desire for rare and expensive products as status symbols. While some products like powdered rhino horn or pangolin scales are used in traditional medicine, modern clientele purchase animal pelts, ivory decorations, bone carvings, and other wildlife trophies as ways to show off an exorbitant lifestyle. The desire for status drives the harvest of endangered hardwoods for furniture, poaching of animals for fur and leather clothing, big game trophies, “exotic” meats, and rare animal artifacts. For many cultures, the use of wildlife products as medicine or as delicacies has a long history, reaching back to a time before the wildlife involved were on the endangered species list. Shifting cultural institutions can be a long and difficult process, even with support from within cultural groups.

A stock of elephant ivory, confiscated from the illegal wildlife trade. Photo by Julie Larsen, Wildlife Conservation Society.

In addition to the demand for wildlife products like meat, furniture, and decorative items, there is rising interest in exotic pet ownership, driving a trafficking market that extends across the tree of life. From aquarium fish to backyard tigers, wild animals of all kinds are being shipped across the world to end up as pets or exhibit animals in private animal attractions. While many of these animals are bred in captivity rather than captured from the wild, conditions for captive-bred exotics in private homes can be quite poor, and many studies report a high mortality rate for captive-bred exotic pets from the time they are born to the time they are sold to their new owners. With the rise of social media, more and more exotic pet owners are showing off their “cute companions,” not only normalizing the idea of exotic pet ownership, but encouraging and offering resources to interested followers. There are many reasons why owning exotic animals can be harmful both to human and animal populations (many of these are outlined on the DLC website regarding lemurs as pets: read about it here).

Radiated tortoises from Madagascar are a common victim of wildlife trafficking.

While the species affected by trafficking spans taxonomic groups, the geographical sources of illegal wildlife trade are concentrated in areas of high biodiversity and low economic stability. Many of these areas are already experiencing habitat loss due to economic need, so the added pressure of poaching is a double disaster for native species. One of the top drivers of wildlife extraction is poverty. Wealthy buyers will pay extravagant amounts for wildlife products, creating an income for locals. However, the money remains in the pockets of a few wildlife trade kingpins, and little of it reaches the community. Often, people involved in wildlife extraction on the local level have little choice or are being exploited by leaders or officials, and complex histories of economic and political turmoil can exacerbate these issues. The IUCN lists human use as a major cause of endangerment for 958 species, and about 24% of all recognized vertebrate species are victimized by the wildlife trade. Solving the wildlife crime problem starts with support for impoverished communities in areas of high biodiversity. With better income options, social and political stability, and less financial dependence on wildlife, many poachers would be able to give up their dangerous livelihoods, and protect endangered species in the process.

Pangolins are the most-trafficked non-human mammal.

The fight against wildlife trafficking is ongoing, but progress is being made. Organizations across the world are fighting for stronger protections, cracking down on customs procedures, and closing legal loopholes in order to keep illegal wildlife smuggling under control. New technology is being introduced to track and identify vulnerable species in shipment. In June 2020, China introduced new legislation to protect pangolins, which are the world’s most-trafficked non-human mammal. Close on the heels of this wonderful progress was Operation Thunder 2020, an international effort in which over 2,000 wildlife and forestry products were seized and 700 individuals apprehended. Thousands of live animals like chimpanzees, tortoises, and a white tiger were seized, recuperated, and released back to the wild. In addition to legal protections, education and advocacy are powerful tools to counter the wildlife trade. Because this trade is driven by consumer demand, consumers have the power to make more informed and sustainable choices about the products they buy and the animals they protect. Few of us may be in the market for leopard skins or alligator boots, but we can make informed choices about what we buy and where it comes from. Stopping illegal wildlife trade is a global effort, but may be possible with global cooperation.

Sources

Astrid Alexandra Andersson, Hannah B. Tilley, Wilson Lau, David Dudgeon, Timothy C. Bonebrake, Caroline Dingle, CITES and beyond: Illuminating 20 years of global, legal wildlife trade, Global Ecology and Conservation, Volume 26, 2021, e01455, ISSN 2351-9894, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gecco.2021.e01455.

CITES. Trade Database. Available online: https://trade.cites.org (accessed on 10 July 2021).

Elizabeth Lunstrum, Nícia Givá. What drives commercial poaching? From poverty to economic inequality, Biological Conservation, Volume 245, 2020, 108505, ISSN 0006-3207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2020.108505.

Scheefers, Brett R, Brunno F. Oliveira, Ieuan Lamb, David P. Edwards. Global wildlife trade across the tree of life. Science 04 Oct 2019 : 71-76.

Shawn Ashley, Susan Brown, Joel Ledford, Janet Martin, Ann-Elizabeth Nash, Amanda Terry, Tim Tristan & Clifford Warwick (2014) Morbidity and Mortality of Invertebrates, Amphibians, Reptiles, and Mammals at a Major Exotic Companion Animal Wholesaler, Journal of Applied Animal Welfare Science, 17:4, 308-321, DOI: 10.1080/10888705.2014.918511

Thomas-Walters, L., Hinsley, A., Bergin, D., Burgess, G., Doughty, H., Eppel, S., MacFarlane, D., Meijer, W., Lee, T.M., Phelps, J., Smith, R.J., Wan, A.K.Y. and Veríssimo, D. (2021), Motivations for the use and consumption of wildlife products. Conservation Biology, 35: 483-491.

William S. Symes, Francesca L. McGrath, Madhu Rao, L. Roman Carrasco, The gravity of wildlife trade, Biological Conservation, Volume 218, 2018, Pages 268-276, ISSN 0006-3207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2017.11.007.