What is a Lemur?

Imagine walking through a rainforest, filled with the signs and sounds of strange wildlife, when you happen upon a furry, large-eyed, leaping animal you have never seen before. There is no guidebook or sign to tell you what this creature is, only what you can see in front of you. Could it be a rodent? A marsupial? Maybe even a primate?

A black and white ruffed lemur surveys their forest enclosure at the DLC.

When encountering a lemur for the first time, many people are not sure what mammal group they belong to. With large eyes, long tails, and wet noses, these Madagascar natives bear resemblances to many familiar species like raccoons, sugar gliders, and other small, tree-climbing creatures. In actuality, lemurs are part of the primate family, but they are some of the earliest primate species to have walked the earth. Being members of the primate family, lemurs share many characteristics with humans, despite having 60 million-odd years between us. In between lemurs and humans on the evolutionary timeline are hundreds of other primate species, from tarsiers to monkeys to apes, all incredibly diverse. So why do we classify all of these species under the primate heading?

The back foot of a red ruffed lemur demonstrates their five-fingered grasping hands AND feet.

Scientists classify the billions of species on earth by examining the characteristics that they share. These characteristics can be ones that are observable during the species’ life, like their physiology, behavior, and adaptations; they can also be less visible to the naked eye, such as bone structures and genetic sequences. Though these methods are always improving and our answers are always changing, classification gives us an idea of how different species are related to each other, and the timeline on which they evolved.

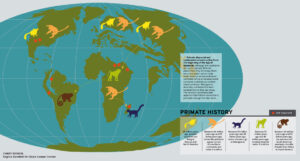

The Primate order is an extremely diverse group, spanning continents and encompassing a wide variety of shapes, sizes, adaptations, habitats, and social groups, but also spanning continents. The earliest strepsirrhine primates are thought to have originated in North America, later migrating to Africa, Asia, and, of course, the island of Madagascar. Lemur-like primates began migrating to Madagascar across the Mozambique channel as early as 55 million years ago. This migration event, likely the result of a chance natural rafting event after a large storm system hit Africa’s coast, would turn out to be extremely significant, as lemurs would later go extinct everywhere except Madagascar.

Since ancestral lemurs and their close relatives were the earliest known primates on earth, they bear a closer resemblance to the other mammal groups living during that time. The closest relatives of the primate family are likely tree shrews, rodents, bats, and colugos (which are not primates despite their common name of “flying lemur”). We can determine that these early primates are distinct from their mammalian ancestors by examining their unique primate features. All primates share the majority of a basic set of characteristics: five -fingered grasping hands, fingernails, forward- facing eyes, relatively large brains, longer life spans and periods of infancy relative to other mammals, and a tendency to live in social groups. All of these qualities are present in lemurs, and though humans often discount our place in the animal kingdom, we possess all of these hallmark primate characteristics as well.

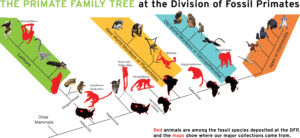

Within the overarching primate family tree are branches to further categorize the highly varied primate species into subgroups. Today, the Primate order is divided into two main groups: the strepsirrhines and the haplorrhines (commonly, but somewhat less accurately, referred to as prosimians and anthropoids). Strepsirrhine primates include lorises, lemurs, and bush babies (or galagoes). Lorises are found in Southeast Asia, while bush babies are found on the African mainland. Haplorrhine species are divided into New World monkeys (native to the Americas), Old World monkeys (native to Africa and Asia), and the ape family, which includes Homo sapiens, or humans. The name “strepsirrhine” refers to the curled, wet nose that these early primates share. This nose is more similar to that of earlier mammal groups (like rodents), and is an indicator that strepsirrhines rely more on olfactory communication than the dry-nosed haplorrhines.

Almost all strepsirrhines have a tooth comb, wherein their bottom six teeth grow forward in a single, fused unit at an outward angle to form a comb-like structure at the front of their jaw. The tooth comb is used for grooming, and a secondary tongue called the sublingua is used like a toothpick to clean the tooth comb. Strepsirrhines also have a grooming claw on their index (second) toe. Haplorrhines lack both of these handy grooming adaptations and instead groom primarily with their dexterous fingers and higher-functioning, fully opposable thumbs. Behaviorally, strepsirrhines are more commonly nocturnal and female-dominant, while the vast majority of haplorrhines are diurnal and male-dominant. These two primate groups also maintain some skeletal differences, such as differing snout lengths and eye sockets.

A male red-bellied lemur shows off his toothcomb.

With over one hundred species of extant (living) lemurs alone, the primate family is incredible in its diversity. Lemurs range in size from the size of a mouse to the size of a small child; can be nocturnal, diurnal, or cathemeral; and have an incredible variety of diets, social structures, and amazing adaptations. With so much diversity, it is certainly understandable that early scientists might have had difficulty placing these amazing creatures in their proper taxonomic home, and it is certainly an honor for us humans to share their branch of the evolutionary tree.