James Herrera, Ph.D., Program Coordinator for DLC-SAVA Conservation. Published December 28, 2020.

Madagascar is a natural and cultural treasure. With over 20,000 known plants and animals found nowhere else on earth, it is one of the biologically richest places on Earth. We continue to discover new species every day (1). Similarly, the diversity of cultures is stunning: More than 18 different ethnic groups are recognized in Madagascar, each with its own dialect and cultural identities. Despite these riches, Madagascar struggles economically, consistently ranking among the 10 poorest countries in the world (2). This year, with the COVID-19 pandemic crippling the globe and especially sub-Saharan Africa, we are quickly losing ground in the race to sustain people and nature in Madagascar.

Though the spread of the coronavirus does appear to have slowed considerably in Madagascar, the country has remained almost entirely closed to international travel since March 2020. At first, strict lockdowns and curfews, testing, and several other measures curtailed the significant spread of the virus. This was a relief, given the grave consequences that a pandemic could have with the fragile health care infrastructure.

The lost economic opportunities have taken a devastating toll, however. Tourism is one of the biggest sources of revenue for the country, and for small businesses in remote country villages. Hundreds of thousands of tourists visit each year, and it is estimated that Madagascar lost almost a billion dollars in revenue from the border closure (3). Hotels, restaurants, and tour guide associations have closed down, and many people have turned to exploiting natural resources to replace lost income.

In remote parts of the island, where lush tropical forests full of lemurs still remain, it is difficult to oversee the massive protected areas. Hunting, logging, and the spread of fire have increased in frequency in protected areas as well as around their borders (4).

The country’s poorest and most marginalized people eke out a living with traditional farming techniques, and some must turn to illegally harvesting natural resources like timber or wild meat to sell. In the arid south, a famine of devastating proportions is forcing 1.5 million people to go hungry every day, mixing clay with the pulp of meager fruits to stave off the hunger pains (5). In the rainforests of the north, hunting lemurs is on the rise (4), with dozens of snare traps set targeting endangered species (6). While some of this hunting is for subsistence, feeding hungry families at home, it is also often for sale. A demand for exotic wild meat in hotels and restaurants in cities has created an opportunity for impoverished households to earn income with wild meat (7).

(To learn more about the use of snare traps in the SAVA region, and how local lemur populations are being monitored and these threats addressed, see James’s article “Conserving Vital Links in the Habitat of Lemurs, Northeast Madagascar.”)

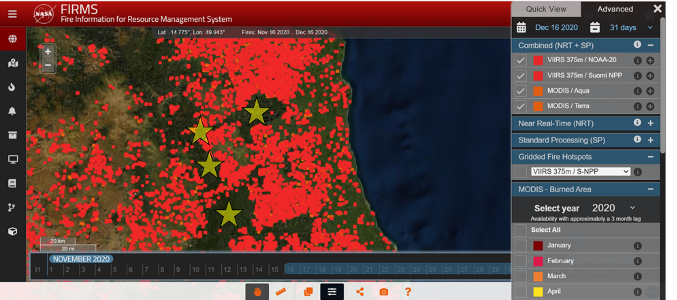

The frequency of fires has escalated to alarming rates across the island (8). Fires are set for many reasons: to clear land for farming and pasture, and to stake a claim to the land and show that the land is in active use by the farmer; and fires escape from charcoal production. Sometimes forest fires are set to express resistance by the local population to authorities whom they believe have unjustly prevented their access to land and resources. The protected areas are rimmed in smoke as the edges contract and boundaries are pushed ever further. While many of the fires may be relatively small-scale, clearing secondary bushes or savanna in degraded lands, many farmers are moving deeper into primary forest to clear land where soils are still fertile, and forests provide enough moisture to support farming.

A screenshot of fire occurrences detected by NASA satellites in the northeast SAVA region. The stars indicate protected areas that are under constant threat from the spread of fires.

A patch of forest within the Marojejy National Park cut and still smoking.

The future may seem bleak given these circumstances. In fact, the World Bank shows that the current economic crisis is comparable to that observed in 2009 during a political coup, and it is predicted it may take a decade for economic recovery (9). There is hope, however, as exemplified by the motivation and unrelenting spirit of Malagasy conservationists. Their efforts to protect natural resources and conserve them for future generations give a glimmer of hope that they will achieve their goals of sustainable development and the management of these precious natural wonders. Universities, locally-initiated NGOs, and government agencies spanning environment, education, and health are coming together to manage their resources sustainably and conserve biodiversity.

For example, in the northeast region known as the SAVA, numerous actors have united in a consortium to execute strategic action plans for biodiversity conservation both inside and outside of protected areas. Called the Committee for the Protection of Biodiversity, the consortium is led by the local university of the SAVA region (CURSA), in close partnership with the Ministry of Environment and Sustainable Development, the Madagascar National Parks, and all the relevant environmental NGOs with conservation programs in the SAVA, including the Duke Lemur Center. Their goals, among many, are 1) sustainable agricultural development through environmentally restorative techniques like agroecology, 2) restoration of natural forests, and 3) the protection and management of existing forests both inside and outside of protected areas.

Founding members of the Committee for the Protection of Biodiversity during their first annual Round Table meeting, February 2020.

First, the local university, CURSA, is developing an agricultural department to conduct research and provide extension services to local farmers. Their goal is to train students in advanced approaches in regenerative agriculture including agroforestry, conservation agriculture, and nature-based solutions to challenges farmers face such as erosion and watershed protection, crop rotation and climate-smart crop choice to address failing harvests in the dry season, and more. Since cash crops like cloves, cacao, and vanilla are staples in SAVA agriculture, CURSA is developing research and extension including approaches to diversified agroforesty that include trees on the landscape while also allowing low impact farming of diverse annual food crops. With support from the General Mills, DLC and CURSA are partnering to develop and implement training programs and strengthen skills with local partners (10, 11). This action plan addresses some of the main drivers of deforestation and degradation in Madagascar, including food insecurity, poverty, unsustainable traditional farming techniques, and access to extension services to develop sustainable diversified farming.

CURSA student intern Veve assists farmer Falimanana as he prepares his agroforestry plantation with cloves, cacao, and native trees.

Second, the entire country is making strides to meet ambitious goals of reforestation and to plant 60 million trees (12). In SAVA, communities in all the local districts are setting aside land to protect it from fires, allow the natural regeneration of native trees, and actively restore the landscape by planting hundreds of thousands of seedlings (13). This year, multiple actors are aligning their reforestation goals with an aim at planting four million seedlings, 1 million in each of the four districts. With partners like CURSA and local communities that pledge to restore forest, DLC is contributing to these efforts by supporting the planting of 40,000 seedlings.

Third, protecting old-growth natural forest is a fundamental requisite to biodiversity conservation. While restoring degraded habitats is an admirable mission, those efforts may never bring back biodiversity to levels comparable to old-growth habitats. Therefore, it is our first priority to prevent further degradation and loss of old-growth habitats. Regarding the SAVA, there are multiple agencies that manage protected areas in the region. The Madagascar National Parks oversees a subset of protected areas with strict, limited access, such as Marojejy and Masoala National Park, and the Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve. The DLC has partnered with MNP for the last decade to support their mission and advance park protection. For example, with support from the IUCN Save Our Species grant, the DLC and MNP demarcated the boundary of the Marojejy National park, placing metal signs around the limit to clearly delineate the boundary. Five years later, much of that boundary is under further pressure, as people living on the border push the limits with fire and destroying signs. DLC has again supported the MNP to replace signage, and create collaboration conventions with local communities to coordinate their active monitoring. MNP now proposes to further clear the boundary to install fire-breaks, which are a fire prevention strategy in which all the vegetation within several meters of the forest is cleared to prevent bush fires from spreading into the park.

Madagascar National Parks and the Duke Lemur Center partnered to clearly delineate the boundaries of the park in areas with increased illegal activities. We forged collaboration conventions with local authorities to coordinate protecting the park.

In another protected area, known as the COMATSA and managed by the World Wildlife Fund, CURSA scientists are conducting multidisciplinary research on lemur ecology, threats to their viability, and the socio-cultural context of natural resource management. They completed an intensive monitoring mission at nine localities during September of 2020 (6), which revealed diverse lemur communities under heavy threat from clear-cutting, logging, and poaching.

The team is now returning to the sites for more data, not only on the lemurs in the forest, but with the people in the villages. The goal is to understand why people use the natural resources the way they do; what are the challenges they are facing that lead them to hunt, clear forest, or cut timber? Together, the research team and local community members are co-creating sustainable management plans. For example, many people report hunting wildlife like lemurs to eat and to earn income from the sale of meat. Interventions to develop chicken husbandry and fish farming are effective alternatives to for replacing precious macro- and micronutrients as well as earned income from the sale of chickens, chicks, eggs, or fish. Similarly, the need for timber and fuel wood can be partially met using sustainable forestry practices that have been tried and tested in multiple tropical regions. By combining efforts to reforest degraded areas with sustainable forestry practices, communities could create long-term timber farms to decrease pressures on natural forests.

These efforts and more are only a part of the puzzle to solve the conservation issues in Madagascar, and around the world. Effective governance is paramount to fair and just societies, which are conducive to nature conservation. Crime, corruption, and leaks in the justice system all preclude effective management of natural resources at the highest levels. Overcoming these challenges will require a united front among the people and politicians to elect leaders who will put the sustainable development of their country at the top of their agenda. These local-, national-, and international level solutions are needed to ensure a more equitable and sustainable approach to environmental conservation. If you are interested in the DLC projects discussed above and want to contribute, consider making a tax-deductible donation.

An example of a snare trap used to hunt lemurs.

2 https://blogs.worldbank.org/africacan/how-severe-will-poverty-impacts-covid-19-be-africa

4 https://www.nationalgeographic.com/animals/2020/12/pandemic-lockdown-endangered-lemurs/

5 https://news.un.org/en/story/2020/11/1078662

6 https://connect-technology.net/SAVA-December2020/#p=8

8 https://news.mongabay.com/2020/12/as-minister-and-activists-trade-barbs-madagascars-forests-burn/

10 https://connect-technology.net/SAVA-December2020/#p=5

11 https://fb.watch/2wCPiIhRqa/

12 https://news.mongabay.com/2020/01/madagascar-launches-massive-planting-drive-eyes-60-million-trees/

13 https://lemur.duke.edu/restoring-forests/