By DLC research scientists Marina Blanco, Ph.D. and Lydia Greene, Ph.D.

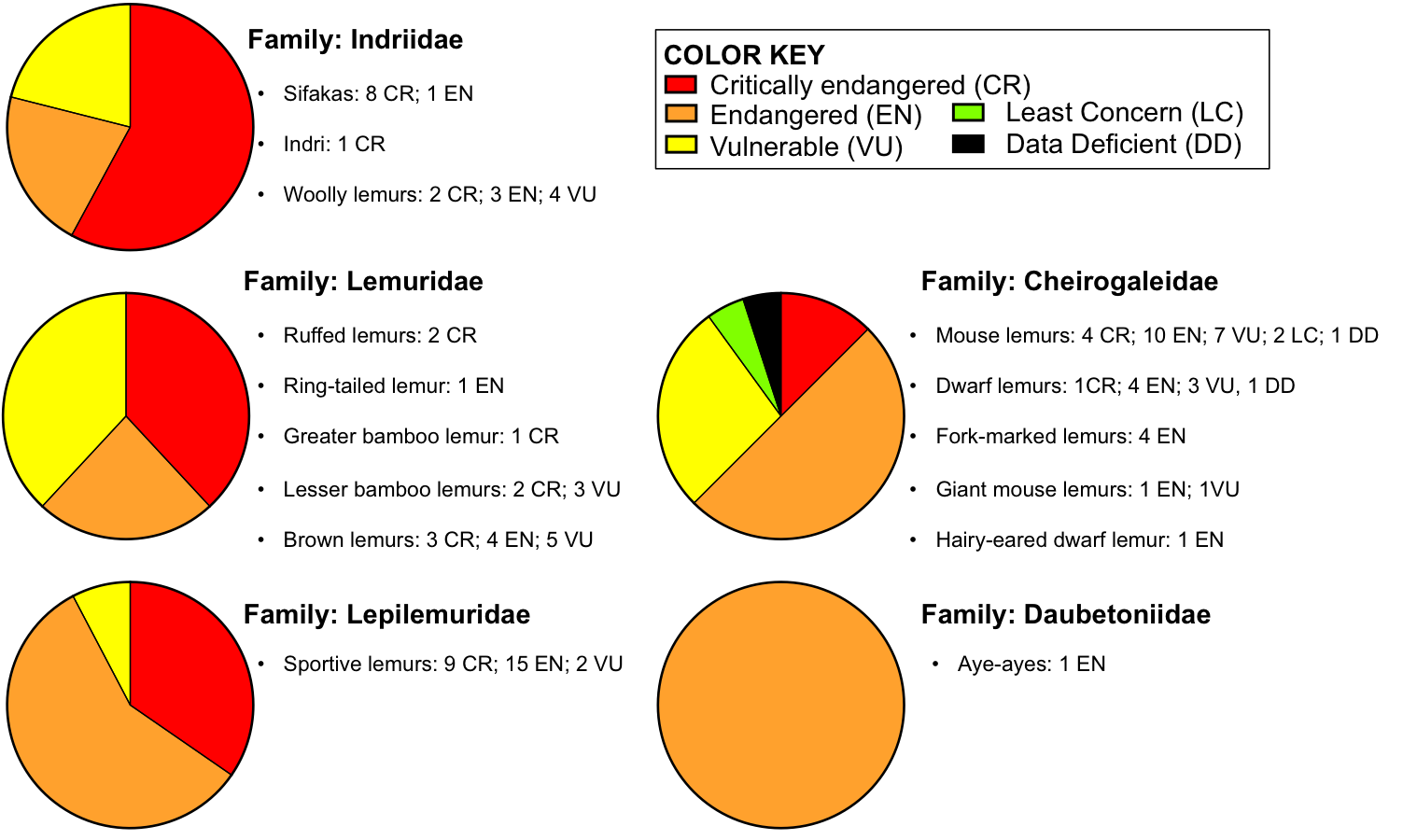

The new conservation assessments for Madagascar’s 107 lemur species have been released by International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), and the updates are, to say the least, alarming. Since the previous assessment, many species have been uplisted, meaning that they are now considered more endangered than they previously were. Currently, about 1/3 of lemur species are listed as Critically Endangered. With the exception of three mouse lemurs and one dwarf lemur, every other species falls into the Endangered or Vulnerable categories.

Pie charts showing the proportion of lemur species within each family that now fall into IUCN categories of endangerment, including critically endangered (red), endangered (orange), vulnerable (yellow), least concern (green), and data deficient (black). The text next to each pie chart lists the number of species within each lemur genus that falls into particular endangerment categories. Click the image for a larger view.

Since the assessments’ release, accruing articles have discussed the devastating effects of ongoing habitat loss on lemur survivorship, made all the worse by COVID-19. And while the consequences of deforestation to Madagascar’s wildlife cannot be overstated, there are numerous factors that can contribute to lemur endangerment — including those that are anthropogenically induced, those that may naturally contribute, and those that result from scientific advancement. All of these factors were discussed at length during the IUCN redlisting meeting, which was held back in 2018. [See Marina’s and Lydia’s article “Notes from the Field: IUCN Red List Meeting in Madagascar,” which discusses their participation at the redlisting meeting and how each species’ endangerment status is assessed.]

Sifakas

One relatively clear-cut case of uplisting due to habitat loss is the western sifakas: The Coquerel’s sifaka, Verreaux’s sifaka, von der Decken’s sifaka, and Crowned sifaka were all uplisted from Endangered to Critically Endangered, which means that 8/9 sifaka species now fall into the category of most extreme threat. The uplisting of the western sifakas reflects significant burning and deforestation in the dry forests, which compared to the rainforests, are also very difficult to regenerate via reforestation efforts.

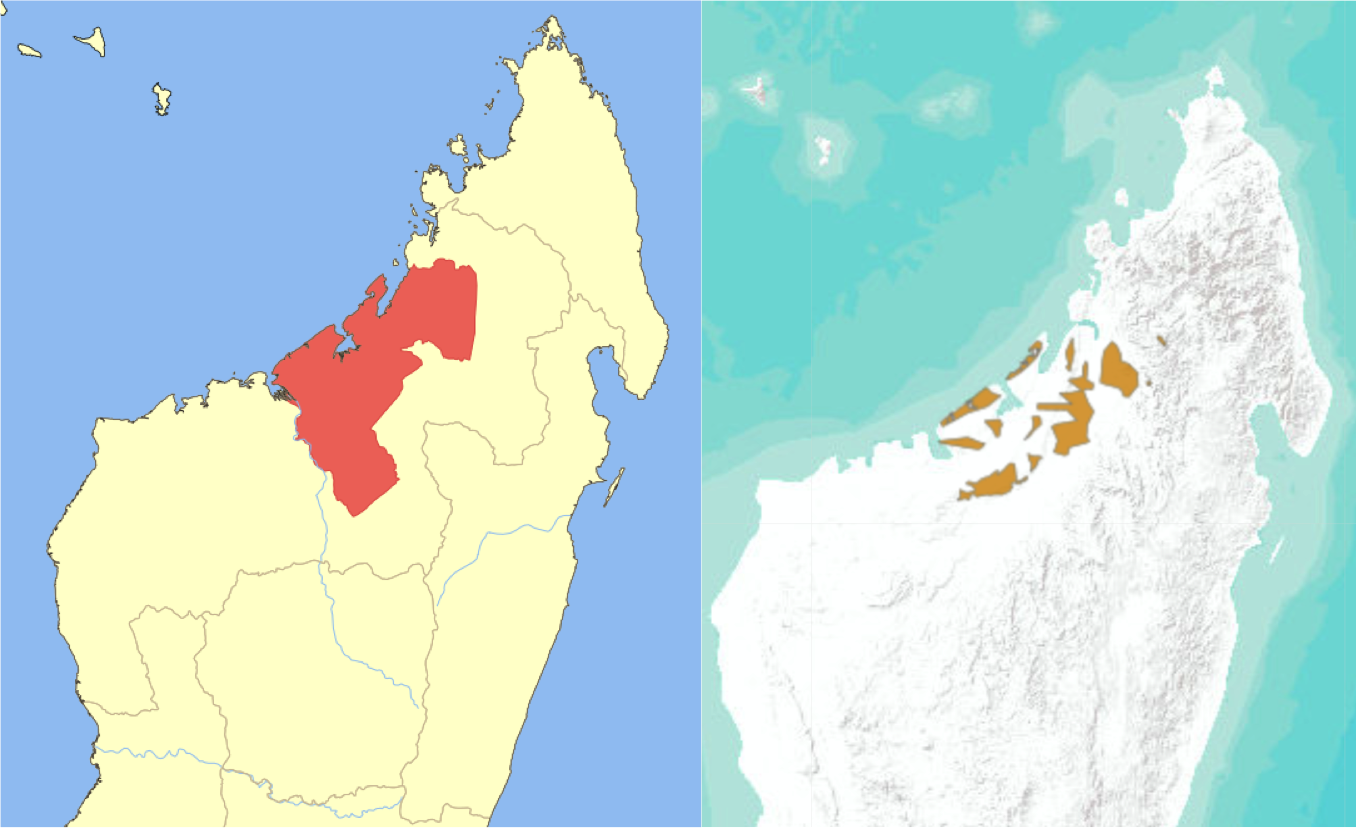

The new assessments considerably updated the range maps for each species too, such that only places with current forest cover and known localities are included, rather than covering the entire region in which the species might be found. The change in maps really drives home how fragmentated these forests have become.

IUCN maps of the Coquerel’s sifaka geographic range in Madagascar stemming from the previous assessment (left) and the current assessment (right).

And yet, forest loss alone doesn’t seem sufficient to explain why sifakas (and other indriids) are so exceptionally endangered. These lemurs live alongside many other lemur species that, on the whole, don’t attain the same threat level. Coupled with habitat loss, indriids are generally large bodied, which means they need more space to support healthy populations. And space is getting harder to come by as forests shrink.

Add to this sifakas’ dietary specialization on leaves. In general, specialized species tend to be more at risk. They often inhabit smaller geographic areas and are less able to buffer the consequences of habitat loss and change (see https://doi.org/10.1002/ajp.23104). This phenomenon doesn’t only apply to the leaf-eating lemurs. Ruffed lemurs — extreme fruit specialists — are seriously critically endangered. And Sibree’s dwarf lemur — an extreme high-altitude specialist — is the most critically endangered of all dwarf lemurs. Thus, the natural ecology of each lemur species can shape how the species may cope with ongoing and future change.

Dwarf lemurs

Another consideration is updates to the lemur family tree. In the past decade, several new species of mouse and dwarf lemur have been discovered. In reality, these discoveries reflect advancements in sampling and genetic sequencing that allow us to better parse whether two groups of lemurs are distinct populations of the same species or are wholly distinct species. Splitting one species with a big geographic range into two (or more) species, inherently ends up with everyone having a smaller geographic range overall.

The case of taxonomic revision coupled with continued habitat loss and updated maps explains why the fat-tailed dwarf lemur was uplisted from Least Concern to Vulnerable. Whereas the fat-tailed dwarf lemur used to occupy the entirety of Madagascar’s dry forests, the northern and southeastern populations have since become their own species, respectively known as the Ankarana and Thomas’ dwarf lemurs.

The range map for the fat-tailed dwarf lemur got even further slashed, due to mounting knowledge that dwarf lemurs do not actually inhabit the southern spiny deserts. Thus, the fat-tailed dwarf lemur is now restricted only to the central-western dry forests, a fraction of what we once considered its former range.

Additional considerations

Although habitat loss was the major focus of the IUCN meeting, other anthropogenic threats were also discussed, with hunting pressure and extirpation for the pet trade being chief among them (see https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31115-7 and https://doi.org/10.1017/S003060531400074X).

For some species, like the aye-aye and the hairy-eared dwarf lemur, assessments were challenged by the sheer sparsity of field data: For many of us, merely seeing these lemurs in the wild is a life-long goal, much less studying them. And consideration of climate change was also present, with the sobering thought shared among many participants that some lemur species may not persist long enough for climate change to become the principal threat.

Ways to help

Despite the rather bleak outlook offered by these assessments and my summary thereof, there are plenty of ways we can help. If you’re wondering how you, a member of the general public, can help lemurs survive into the future, here are some ideas:

Be an informed enthusiast: Learn about your favorite lemur, its home, and the specific threats it faces.

Read up on the aspects of lemurs that you find fascinating. The DLC’s Meet the Lemurs pages are a wonderful place to start!

Host a Zoom-boomafoo meeting with friends, family, or students and share what you’ve learned.

Do your next science project for school on lemurs; take more STEM and conservation classes.

Reach out to your favorite lemur scientist or conservationist, or to your local AZA-accredited facility, and ask how you can get involved in ongoing projects.

Do not purchase or adopt a lemur as a pet, and do not share or like social media posts depicting lemurs being kept as pets. Curious why? Read “Lemurs: The Pet to Regret” to learn more about why the Duke Lemur Center is against all trade in pet primates, and against the holding of any prosimian (lemur, loris, bushbaby, potto) as a pet.

Be an informed tourist: Plan your next vacation to Madagascar (when it’s safe to do so again)

Research eco-tourism sites ahead of time and prioritize places that promote healthy experiences for you and the lemurs. You can even join the DLC on our Magical Madagascar EcoTour in 2021.

Avoid places that allow guests to feed or touch the animals.

Do not take or share pictures of you touching lemurs in Madagascar. Help keep wildlife wild.

Prioritize patronizing local and Malagasy-operated ventures.

Do not eat bushmeat; try the ravitoto or hena omby instead!

Be an informed donor: Fundraise for your favorite lemur organization. No amount of money is too small.

Prioritize organizations that are Malagasy-led or that partner with Malagasy-led organizations.

Prioritize organizations that hire Malagasy experts and staff.

Learn about the organization’s goals and specific projects; learn how success is measured.

Looking for a great place to start? Learn more about the DLC’s conservation initiatives, where we’ve worked for over 35 years with the people and organizations of Madagascar to protect lemurs and their natural habitat while simultaneously supporting the livelihoods of rural people.