Cheirogaleus medius

The fat-tailed dwarf lemur is the only primate in the world known to hibernate for an extended period of time.* Hibernation can last up to seven months and is defined by periods of torpor (severely decreased metabolism, heart rate, and body temperature) interspersed with metabolically active periods of rewarming called interbout arousals. Interbout arousals tend to occur every 6-12 days during hibernation.

During torpor, a fat-tailed dwarf lemur’s heart rate drops from about 200-300 beats per minute to as low as six beats per minute. Its body temperature drops, too, and becomes driven by the ambient temperature of the environment.

During an interbout arousal, a dwarf lemur’s body temperature rises, its heart rate increases, its breathing becomes more regular, and its brain shows massive bouts of REM sleep. Afterward, the animal drops back into torpor.

Before hibernating, dwarf lemurs begin accumulating fat in their tails by gorging on food during the wet season (when fruits and flowers are more abundant) in preparation for the dry season when these foods are more scarce. During their period of gorging, dwarf lemurs’ tails can reach up to 40% of the lemurs’ total body weight (hence the namesake “fat tail”). They then enter a state of hibernation, living off of the fat stored in their tails.

*Mouse lemurs are also capable of torpor, but torpor bouts in these animals are typically shorter than 24 hours.

About Fat-tailed Dwarf Lemurs

Adopt a Fat-tailed Dwarf Lemur

Want to learn more about fat-tailed dwarf lemurs AND help support their care and conservation not only here but also in Madagascar? Consider symbolically adopting Raven, a female fat-tailed dwarf lemur, through the DLC’s Adopt a Lemur Program! Your adoption goes toward the $8,400 per year cost it takes to care for each lemur at the DLC, as well as aiding our conservation efforts in Madagascar. You’ll also receive quarterly updates and photos, making this a fun, educational gift that keeps giving all year long!

How does hibernation work?

Fat-tailed dwarf lemurs are the only primates capable of hibernating for extended periods of time. Hibernation can last up to seven months and is defined by periods of torpor (severely decreased metabolism, heart rate, and body temperature) interspersed with metabolically active periods of rewarming called interbout arousals.

In preparation for torpor, a fat-tailed dwarf lemur can increase its body weight by 75g (about 40%) at a time. It effectively gorges during times of food abundance, to prepare for Madagascar’s dry season when its diet of fruits and flowers is scarce. In the winter months, most dwarf lemurs enter a state of hibernation. During torpor, dwarf lemurs experience a slow-down in their metabolic rates and show a marked decrease in activity and appetite which may last for up to seven months. During this period, these lemurs live off of fat stored in their tails.

Hibernation begins as early as March in Madagascar, when the dwarf lemurs retreat to shelters such as those offered by hollow tree trunks. They sometimes do not emerge until the beginning of the wet, hot season in November. Up to five animals may be found huddled together during this period.

To learn more about how dwarf lemur hibernation works and if humans could hibernate in real life, check out this informative and adorably illustrated video by Sheena Faherty, one of former DLC Director Anne Yoder’s former graduate students. While pursuing her Ph.D. here at Duke, Sheena studied the only primates capable of hibernation behavior: the fat-tailed dwarf lemurs of Madagascar!

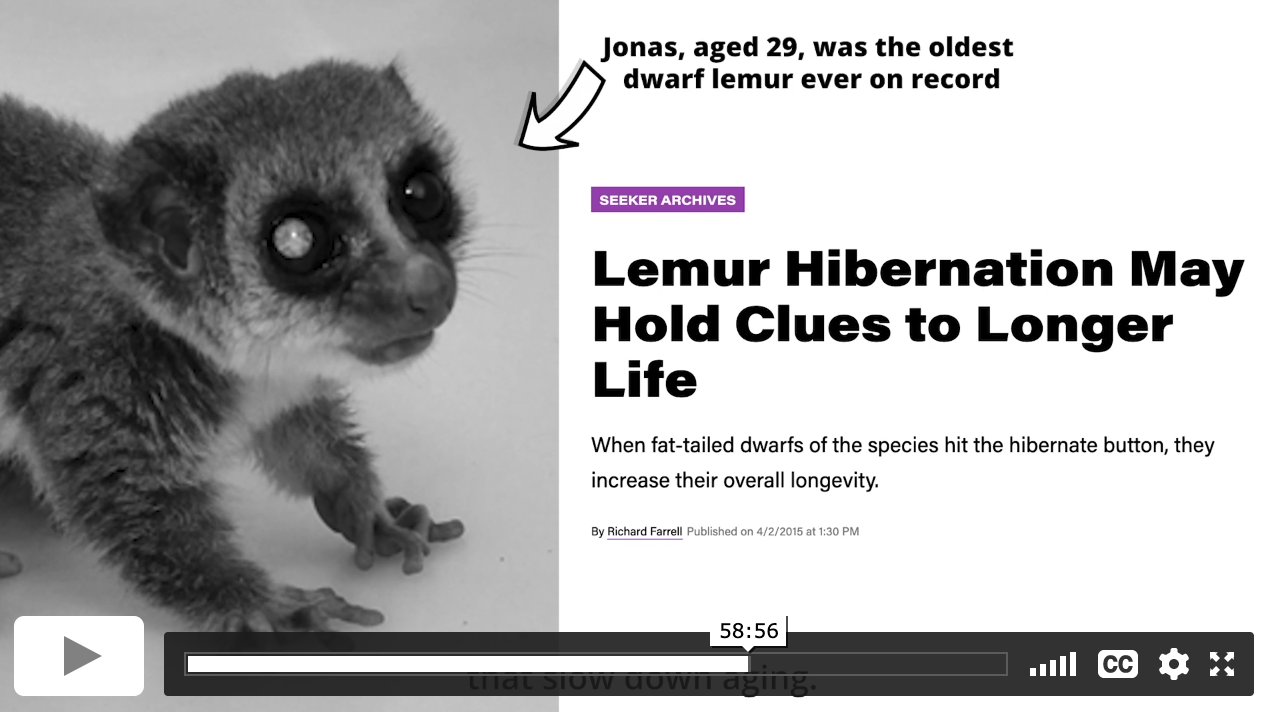

If you'd like to learn even more about these amazing hibernating primates, check out the talk Sheena gave at the DLC’s 50th-anniversary scientific symposium: “Gene expression and physiological extremes in primate hibernation”. You can also read the article "Could People Hibernate? Lemurs Give Clues" published in National Geographic, which discusses how studying hibernation in fat-tailed dwarf lemurs can help people, too - from terminally ill patients to soldiers and astronauts.

Videos

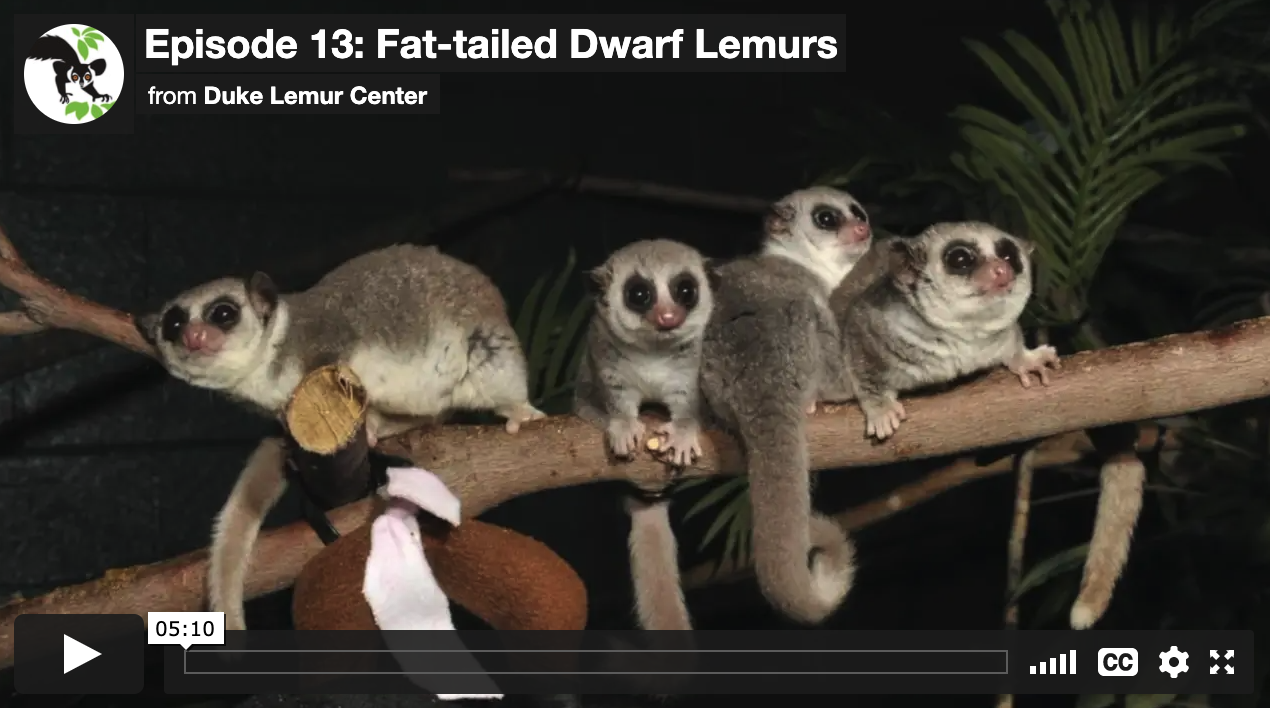

Fat-tailed dwarf lemurs are featured in episodes 10 and 13 of our FREE virtual tour series! Learn how the fat-tailed dwarf lemur earns its funny name, how its body responds to hibernation and torpor, and why studying its remarkable habits could have a huge impact in the human world.

From 56:06-1:04:30 of our feature-length video Me and You and Zoboomafoo, we’ll take a deep dive into the research of one of the DLC’s staff scientists, Marina Blanco, Ph.D., who studies hibernation in fat-tailed dwarf lemurs at the DLC and in Madagascar. Dr. Blanco’s research illustrates how non-invasively studying lemurs can help not only the lemurs themselves, but have major implications for human health and technology—including insights on aging, diabetes, obesity, and even space travel and deep hibernation.

In 2014, our fat-tailed dwarf lemurs played a featured role in the IMAX film, Island of Lemurs: Madagascar. Watch them get ready for their closeup with this behind-the-scenes footage.

To learn more about how dwarf lemur hibernation works and if humans could hibernate in real life, check out this informative and adorably illustrated video by Sheena Faherty, one of former DLC Director Anne Yoder’s former graduate students. While pursuing her Ph.D. here at Duke, Sheena studied the only primates capable of hibernation behavior: the fat-tailed dwarf lemurs of Madagascar!

The lemur family tree is full of unique adaptations, from striped tails to tapping fingers! But only one lemur an help us unlock the secrets of space... Wait, what?! Join the Bizarre Beasts Show for a peek into the world of hibernating lemurs, and what we can learn about ourselves from non-invasive research right here at the DLC!

Click HERE to watch a video of 1.5-month-old fat-tailed dwarf lemur triplets Albatross, Bustard, and Elephant Bird playing with each other independently of mom Emu. Once they go back to mom, they seem eager to groom and nurse.

Diet

Nocturnal solitary foragers, dwarf lemurs have a diverse diet consisting mostly of fruit and flower nectar. While they are thought to be less carnivorous than mouse lemurs, they will also eat insects and small vertebrates.

To prevent obesity in our dwarf and mouse lemurs during their torpor season, the DLC has established a “winter diet” and a “summer diet.” The winter diet is initiated in early to mid-September, with a gradual decrease in rations fed to the animals. Starting in mid-March the diet is then increased gradually, reaching the full summer diet amount during the breeding season. Without the reduced rations of the winter months, the dwarf lemurs would continue to consume any and all food provided, which, coupled with a greatly reduced rate of metabolism, could result in extremely overweight animals!

Size and Appearance

Researchers in Madagascar have recently realized there are many more species of dwarf lemur than the two previously recognized. The species housed at the Duke Lemur Center, Cheirogaleus medius, is about 8 inches (20 cm) long, about the same body size as a chipmunk. In the summer, fat-tailed dwarf lemurs weigh around 7 ounces (200 g). In the winter, dwarf lemurs rely on fat stored in their tail for energy. Prior to the start of their hibernation, they gain up to 40% of their body weight, weighing around 9 ounces (270 g). These tails are just as long as the body of the lemur but change shape as they gain weight, giving them the species their common name.

As small, nocturnal lemurs, fat-tailed dwarf lemurs do not have brightly patterned fur. They are predominantly gray with white fur along the inside of their legs and along their ventral side. These colors help them blend into the trees the lemurs live in, making them difficult to spot by barn owls that hunt them.

Reproduction

The strong seasonality of breeding found in mouse and dwarf lemurs depends upon a variable “photoperiod,” or day length. Dwarf lemurs breed at the DLC from mid-April through July. Gestation is around 60 days. Fat-tailed dwarf lemurs commonly have litters of two or more offspring. Of the 168 fat-tailed dwarf lemurs born at the DLC from our founding through July 2019, 10% were singletons, 38% were twins, 35% were triplets, and 17% were quadruplets.

All dwarf lemurs at the DLC are provided with a wide variety of nestboxes, including PVC tubes, wooden boxes, and suspended enrichment boxes all suitable for sleeping and raising young. Mothers give birth in the nestboxes and generally will keep their infants hidden inside these shelters. If they need to move their offspring, they do so by carrying them in their mouths. Mouse and dwarf lemur offspring of up to three weeks of age are transported by the mother in this fashion, but by the time the infants are two months old, they are behaving much like adults and are capable of independent locomotion.

On average, dwarf lemurs reach sexual maturity at one year of age, although females generally are not capable of giving birth until they are 18 months of age. In the wild, juvenile dwarf lemurs tend to enter their first period of dormancy later than adults, perhaps providing the youngsters with a period of reduced feeding competition in which to put on additional pre-torpor weight.

Behavior

Dwarf lemurs forage alone at night. During the day they congregate, in groups of up to five, in a tree hole while they sleep. The composition of these sleeping groups changes seasonally, and often animals choose to sleep alone.

Sleeping sites generally consist of hollow trees, whose cavities have been cushioned with leaves. Otherwise, dwarf lemurs will make spherical nests out of dead leaves they concealed in heavy undergrowth.

Click HERE to see dwarf lemurs nesting in a tree hole in Tsihomanaomby, a subhumid forest in northern Madagascar.

Females generally occupy “home ranges” in central areas of a group’s range, while a single male may overlap his home range with those of several females.

Habitat and Conservation

The species of dwarf lemur found at the DLC, Cheirogaleus medius, is native to the dry deciduous forests of western and southern Madagascar. These small lemurs can live in primary forests, established secondary forests as well as the gallery forest of the southern spiny desert.

Dwarf lemurs may be responsible for pollinating some species of baobab trees. In addition, they play an important role in the ecology of the tropical forest by aiding in the dispersal of small seeds. As a part of their normal scent marking routine, dwarf lemurs often smear feces onto branches as they walk along well-traveled arboreal pathways through the forest, thereby providing a perfect microclimate for the germination of parasitic plants and epiphytes common in the forest.

When only two species of dwarf lemurs were recognized—one throughout the eastern forests, one in the western forests—both were considered widespread and thus not highly endangered. However, now that the genus has been reclassified into several species with more limited distribution, the conservation status of each species needs to be re-evaluated. Their small size, nocturnality, and ability to live in secondary forests may provide them with more protection; but, as with all lemurs of Madagascar, habitat destruction increasingly threatens their survival. Primary threats to dwarf lemurs' habitat include slash-and-burn agriculture, charcoal production, and brushfires.

Quick Facts

Adult size: 0.4 – 0.6 pounds (120 to 270 g)

Social life: solitary forager, strictly nocturnal, sleeps in groups of up to five individuals

Habitat: western dry deciduous forests

Diet: fruit, flowers (nectar), and occasional insects and small vertebrates

Sexual maturity: 1.5 years

Mating: extremely seasonal

Gestation: 61 – 64 days

Number of offspring: one to four infants per litter, one litter each year

DLC naming theme: birds

Malagasy name: Matavirambo, Kely Be-hohy, Tsidihy

How You Can Help

Send a lemur a present: You can send special treats to the DLC’s lemurs, as well as raw materials for us to construct special enrichment activities to keep them happy and healthy. Simply visit our amazon.com wishlist! Dwarf lemurs in particular really enjoy the cozy beds (such as the fleece nesting pouch pictured above) and hammocks often featured on our wishlist.

Adopt a fat-tailed dwarf lemur: Want to learn more about this species AND help support their care, not only here but also in Madagascar? Consider symbolically adopting Raven, a female fat-tailed dwarf lemur, through the DLC’s Adopt a Lemur program! Adoption packages start at just $50.

Visit the Duke Lemur Center: The DLC is only partially funded by Duke, so we rely heavily on revenue from tours to help pay for lemur care and housing as well as our conservation work in Madagascar. So, something as simple and fun as visiting the Lemur Center can help us help the lemurs!

Engage in conservation locally: Though it doesn't directly affect lemurs, the DLC also promotes local conservation. We encourage visitors to support local ecosystems and protect local habitats, similar to the way we're helping the local people in Madagascar preserve lemurs' natural habitat. A fun way to do this is to plant a local pollinators garden at your home or school. The DLC itself has incorporated a Monarch Waystation into its landscaping for the summer tour path in 2017. You can also stop using dangerous chemicals on your lawn, which might end up in lakes and streams and harm fish, frogs, and other animals.

Want to learn more about fat-tailed dwarf lemurs AND help support their care and conservation not only here but also in Madagascar? Consider symbolically adopting Raven, a female fat-tailed dwarf lemur, through the DLC’s Adopt a Lemur Program! Your adoption goes toward the $8,400 per year cost it takes to care for each lemur at the DLC, as well as aiding our conservation efforts in Madagascar. You’ll also receive quarterly updates and photos, making this a fun, educational gift that keeps giving all year long!

Fat-tailed dwarf lemurs are the only primates capable of hibernating for extended periods of time. Hibernation can last up to seven months and is defined by periods of torpor (severely decreased metabolism, heart rate, and body temperature) interspersed with metabolically active periods of rewarming called interbout arousals.

In preparation for torpor, a fat-tailed dwarf lemur can increase its body weight by 75g (about 40%) at a time. It effectively gorges during times of food abundance, to prepare for Madagascar’s dry season when its diet of fruits and flowers is scarce. In the winter months, most dwarf lemurs enter a state of hibernation. During torpor, dwarf lemurs experience a slow-down in their metabolic rates and show a marked decrease in activity and appetite which may last for up to seven months. During this period, these lemurs live off of fat stored in their tails.

Hibernation begins as early as March in Madagascar, when the dwarf lemurs retreat to shelters such as those offered by hollow tree trunks. They sometimes do not emerge until the beginning of the wet, hot season in November. Up to five animals may be found huddled together during this period.

To learn more about how dwarf lemur hibernation works and if humans could hibernate in real life, check out this informative and adorably illustrated video by Sheena Faherty, one of former DLC Director Anne Yoder’s former graduate students. While pursuing her Ph.D. here at Duke, Sheena studied the only primates capable of hibernation behavior: the fat-tailed dwarf lemurs of Madagascar!

If you'd like to learn even more about these amazing hibernating primates, check out the talk Sheena gave at the DLC’s 50th-anniversary scientific symposium: “Gene expression and physiological extremes in primate hibernation”. You can also read the article "Could People Hibernate? Lemurs Give Clues" published in National Geographic, which discusses how studying hibernation in fat-tailed dwarf lemurs can help people, too - from terminally ill patients to soldiers and astronauts.

Fat-tailed dwarf lemurs are featured in episodes 10 and 13 of our FREE virtual tour series! Learn how the fat-tailed dwarf lemur earns its funny name, how its body responds to hibernation and torpor, and why studying its remarkable habits could have a huge impact in the human world.

From 56:06-1:04:30 of our feature-length video Me and You and Zoboomafoo, we’ll take a deep dive into the research of one of the DLC’s staff scientists, Marina Blanco, Ph.D., who studies hibernation in fat-tailed dwarf lemurs at the DLC and in Madagascar. Dr. Blanco’s research illustrates how non-invasively studying lemurs can help not only the lemurs themselves, but have major implications for human health and technology—including insights on aging, diabetes, obesity, and even space travel and deep hibernation.

In 2014, our fat-tailed dwarf lemurs played a featured role in the IMAX film, Island of Lemurs: Madagascar. Watch them get ready for their closeup with this behind-the-scenes footage.

To learn more about how dwarf lemur hibernation works and if humans could hibernate in real life, check out this informative and adorably illustrated video by Sheena Faherty, one of former DLC Director Anne Yoder’s former graduate students. While pursuing her Ph.D. here at Duke, Sheena studied the only primates capable of hibernation behavior: the fat-tailed dwarf lemurs of Madagascar!

The lemur family tree is full of unique adaptations, from striped tails to tapping fingers! But only one lemur an help us unlock the secrets of space... Wait, what?! Join the Bizarre Beasts Show for a peek into the world of hibernating lemurs, and what we can learn about ourselves from non-invasive research right here at the DLC!

Click HERE to watch a video of 1.5-month-old fat-tailed dwarf lemur triplets Albatross, Bustard, and Elephant Bird playing with each other independently of mom Emu. Once they go back to mom, they seem eager to groom and nurse.

Nocturnal solitary foragers, dwarf lemurs have a diverse diet consisting mostly of fruit and flower nectar. While they are thought to be less carnivorous than mouse lemurs, they will also eat insects and small vertebrates.

To prevent obesity in our dwarf and mouse lemurs during their torpor season, the DLC has established a “winter diet” and a “summer diet.” The winter diet is initiated in early to mid-September, with a gradual decrease in rations fed to the animals. Starting in mid-March the diet is then increased gradually, reaching the full summer diet amount during the breeding season. Without the reduced rations of the winter months, the dwarf lemurs would continue to consume any and all food provided, which, coupled with a greatly reduced rate of metabolism, could result in extremely overweight animals!

Researchers in Madagascar have recently realized there are many more species of dwarf lemur than the two previously recognized. The species housed at the Duke Lemur Center, Cheirogaleus medius, is about 8 inches (20 cm) long, about the same body size as a chipmunk. In the summer, fat-tailed dwarf lemurs weigh around 7 ounces (200 g). In the winter, dwarf lemurs rely on fat stored in their tail for energy. Prior to the start of their hibernation, they gain up to 40% of their body weight, weighing around 9 ounces (270 g). These tails are just as long as the body of the lemur but change shape as they gain weight, giving them the species their common name.

As small, nocturnal lemurs, fat-tailed dwarf lemurs do not have brightly patterned fur. They are predominantly gray with white fur along the inside of their legs and along their ventral side. These colors help them blend into the trees the lemurs live in, making them difficult to spot by barn owls that hunt them.

The strong seasonality of breeding found in mouse and dwarf lemurs depends upon a variable “photoperiod,” or day length. Dwarf lemurs breed at the DLC from mid-April through July. Gestation is around 60 days. Fat-tailed dwarf lemurs commonly have litters of two or more offspring. Of the 168 fat-tailed dwarf lemurs born at the DLC from our founding through July 2019, 10% were singletons, 38% were twins, 35% were triplets, and 17% were quadruplets.

All dwarf lemurs at the DLC are provided with a wide variety of nestboxes, including PVC tubes, wooden boxes, and suspended enrichment boxes all suitable for sleeping and raising young. Mothers give birth in the nestboxes and generally will keep their infants hidden inside these shelters. If they need to move their offspring, they do so by carrying them in their mouths. Mouse and dwarf lemur offspring of up to three weeks of age are transported by the mother in this fashion, but by the time the infants are two months old, they are behaving much like adults and are capable of independent locomotion.

On average, dwarf lemurs reach sexual maturity at one year of age, although females generally are not capable of giving birth until they are 18 months of age. In the wild, juvenile dwarf lemurs tend to enter their first period of dormancy later than adults, perhaps providing the youngsters with a period of reduced feeding competition in which to put on additional pre-torpor weight.

Dwarf lemurs forage alone at night. During the day they congregate, in groups of up to five, in a tree hole while they sleep. The composition of these sleeping groups changes seasonally, and often animals choose to sleep alone.

Sleeping sites generally consist of hollow trees, whose cavities have been cushioned with leaves. Otherwise, dwarf lemurs will make spherical nests out of dead leaves they concealed in heavy undergrowth.

Click HERE to see dwarf lemurs nesting in a tree hole in Tsihomanaomby, a subhumid forest in northern Madagascar.

Females generally occupy “home ranges” in central areas of a group’s range, while a single male may overlap his home range with those of several females.

The species of dwarf lemur found at the DLC, Cheirogaleus medius, is native to the dry deciduous forests of western and southern Madagascar. These small lemurs can live in primary forests, established secondary forests as well as the gallery forest of the southern spiny desert.

Dwarf lemurs may be responsible for pollinating some species of baobab trees. In addition, they play an important role in the ecology of the tropical forest by aiding in the dispersal of small seeds. As a part of their normal scent marking routine, dwarf lemurs often smear feces onto branches as they walk along well-traveled arboreal pathways through the forest, thereby providing a perfect microclimate for the germination of parasitic plants and epiphytes common in the forest.

When only two species of dwarf lemurs were recognized—one throughout the eastern forests, one in the western forests—both were considered widespread and thus not highly endangered. However, now that the genus has been reclassified into several species with more limited distribution, the conservation status of each species needs to be re-evaluated. Their small size, nocturnality, and ability to live in secondary forests may provide them with more protection; but, as with all lemurs of Madagascar, habitat destruction increasingly threatens their survival. Primary threats to dwarf lemurs' habitat include slash-and-burn agriculture, charcoal production, and brushfires.

Adult size: 0.4 – 0.6 pounds (120 to 270 g)

Social life: solitary forager, strictly nocturnal, sleeps in groups of up to five individuals

Habitat: western dry deciduous forests

Diet: fruit, flowers (nectar), and occasional insects and small vertebrates

Sexual maturity: 1.5 years

Mating: extremely seasonal

Gestation: 61 – 64 days

Number of offspring: one to four infants per litter, one litter each year

DLC naming theme: birds

Malagasy name: Matavirambo, Kely Be-hohy, Tsidihy

Send a lemur a present: You can send special treats to the DLC’s lemurs, as well as raw materials for us to construct special enrichment activities to keep them happy and healthy. Simply visit our amazon.com wishlist! Dwarf lemurs in particular really enjoy the cozy beds (such as the fleece nesting pouch pictured above) and hammocks often featured on our wishlist.

Adopt a fat-tailed dwarf lemur: Want to learn more about this species AND help support their care, not only here but also in Madagascar? Consider symbolically adopting Raven, a female fat-tailed dwarf lemur, through the DLC’s Adopt a Lemur program! Adoption packages start at just $50.

Visit the Duke Lemur Center: The DLC is only partially funded by Duke, so we rely heavily on revenue from tours to help pay for lemur care and housing as well as our conservation work in Madagascar. So, something as simple and fun as visiting the Lemur Center can help us help the lemurs!

Engage in conservation locally: Though it doesn't directly affect lemurs, the DLC also promotes local conservation. We encourage visitors to support local ecosystems and protect local habitats, similar to the way we're helping the local people in Madagascar preserve lemurs' natural habitat. A fun way to do this is to plant a local pollinators garden at your home or school. The DLC itself has incorporated a Monarch Waystation into its landscaping for the summer tour path in 2017. You can also stop using dangerous chemicals on your lawn, which might end up in lakes and streams and harm fish, frogs, and other animals.