What’s in a Brain? Primate Cognition

What animal on earth has the largest brain? At 20 pounds, the world’s largest brain swims around deep in the ocean inside of the sperm whale. But having a gigantic brain doesn’t mean these whales are the smartest animals on Earth. While a larger brain is often thought of as being an indicator of greater intelligence, it’s much more complicated than that. One group of animals that is famous for having big brains is the primate family, which includes lemurs, monkeys, apes, and humans. Because humans have such unique brains but are so closely related to other primates, scientists have long been curious about just how intelligent our primate relatives are. By looking at brain size and complexity as well as primate behaviors, we can begin to understand what “smart” looks like for a non-human primate.

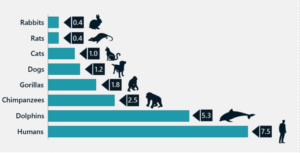

This graph compares the brain to body size ratio for different animals.

Across the animal kingdom, brains come in all shapes and sizes. One of the most important things that scientists look at when determining an animal’s intelligence isn’t just the size of their brain, but how big their brain is compared to the size of their body. While a sperm whale’s brain might be much bigger than a human’s, its body is so much bigger in proportion that its brain isn’t relatively that big after all. Because the brain is such a complicated organ made up of many parts, there is a lot of variability in brain size and shape, even on the individual level. However, we do see trends in how different parts of the brain that are related to certain functions (like memory) might look different from one type of animal to another. Primates (including humans), have a highly-developed pre-frontal cortex, which is responsible for abstract thought and learning. Other animal groups like reptiles, birds, and fish have a much smaller pre-frontal cortex compared to the rest of their brain. When trying to understand why some animals have larger or more complex brains than others, scientists look at other trends in the animals’ ecology or behavior to evaluate how and why larger brains evolved.

Because bigger brains require so much more energy to work, the benefits of having more intelligence have to outweigh the cost of powering that brain. Some research has shown that larger social groups are correlated with larger or more complex brains. Animals living in large, hierarchical groups might benefit from a better memory of “who‘s who” in the group, or need to make strategic alliances in order to stay in the group and to benefit from it. Being “smart” enough to stay in a social group can result in more personal protection, cooperative foraging, access to mates, and even infant care. Almost all primates are social, and many live in large, complex social groups.

Lemurs are highly social and female-dominant.

In addition to the “social smarts,” there is a correlation between animals that eat fruit and animals that have larger brains. Frugivores (fruit eaters) are suggested to have greater intelligence because of the complexity of their diet—they need to be able to recognize many different varieties of fruits, tell whether they’re safe to eat, and remember where they grow and when they ripen. Having the brain capacity to forage this way allows primates, who are primarily frugivorous, to forage more efficiently and eat food that is higher in calories (which helps power those big brains!).

The face of a genius.

Of course, the most well-known indicator of intelligence in primates has to do not only with their brains, but with their hands. Many species of primate are known for using tools. For example, chimpanzees are known for fishing termites out of mounds using twigs that they have shaped to work for this purpose. Other primates might shape rocks into hammers or axes to serve their needs. The ability to identify and solve problems by manipulating objects requires higher cognitive function, but primates are also helped along by their opposable thumbs. Their dexterity allows them to hold and use objects in a way that other animals can’t, but in spite of this, primates aren’t the only known tool-users on the planet. New research into members of the corvid family, which includes ravens and crows, has shown that these birds are also capable of using tools. While these “bird brains” are much smaller than a chimp’s, the brains of crows and ravens are still much larger than those of their avian counterparts.

A chimpanzee uses a tool to extract insects…

…and so does a crow.

Measuring just how “smart” an animal is can be a complicated task—we even struggle to do so in our own human classrooms. While some students may be excellent test-takers, others might be better at presentations, and so on. Testing an animal’s cognitive capability by setting them tasks may make it hard to compare between different species or individuals. Furthermore, what we humans think of as “intelligence” may not have anything to do with how that animal survives in the wild. The more we study animal brains, the more we learn about the incredible capabilities of those brains, and the closer we come to understanding what is so unique about the human brain.

References

BECK, BENJAMIN Β. “Primate tool behavior.” Socioecology and psychology of primates. De Gruyter Mouton, 2011. 413-448.

Falk, Dean. “Evolution of the primate brain.” Handbook of palaeoanthropology 2 (2007): 1133-62.

Gignac, Gilles, Philip A. Vernon, and John C. Wickett. “Factors influencing the relationship between brain size and intelligence.” The scientific study of general intelligence. Pergamon, 2003. 93-106.

Isler, Karin, and Carel P. van Schaik. “The expensive brain: a framework for explaining evolutionary changes in brain size.” Journal of human evolution 57.4 (2009): 392-400.

Matsuzawa, Tetsuro. “Primate foundations of human intelligence: a view of tool use in nonhuman primates and fossil hominids.” Primate origins of human cognition and behavior. Springer, Tokyo, 2008. 3-25.

McGrew, W. C. “Is primate tool use special? Chimpanzee and New Caledonian crow compared.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 368.1630 (2013): 20120422.

Reader, Simon M., and Kevin N. Laland. “Social intelligence, innovation, and enhanced brain size in primates.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 99.7 (2002): 4436-4441.