By Orion Kornfeld with Karie Whitman and Matt Borths, Ph.D. Published in the 2022 Duke Lemur Center annual magazine. Read the original here.

Duke undergraduate Orion Kornfeld in the DLC fossil preparation lab using an Airscribe to remove rock from a 50-million-year-old jaw of a rhino-like creature. The jaw was discovered in Wyoming, USA in July 2022 by the DLC field crew.

The Duke Lemur Center Museum of Natural History (DLCMNH) is the only fossil preparation lab at Duke University. “The fossils at the DLC teach us when, where, and how the ancestors of lemurs and humans adapted to an ever-changing world,” says Curator Matt Borths, Ph.D. “By studying our ecological past, we can discover how to cultivate a more biodiverse future.”

At the DLCMNH, Duke students can work with DLC paleontologists in all stages of paleontological research, from collecting fossils to fossil stabilization, accessioning, scanning, sampling, and publication. One such student is Orion Kornfeld, a Duke sophomore who began working at the DLCMNH as a freshman.

Where are you from and what do you study at Duke?

ORION: I was born and raised in St. Louis, Missouri. I’ve always been interested in both psychology and paleontology, so I currently study evolutionary anthropology, which is probably the only major in the world that combines the two.

How did you learn about the DLCMNH fossil collection?

ORION: I originally learned about it through its website. Dr. Matt Borths was kind enough to meet with me via Zoom before I even applied to Duke, and he told me all about the collection. The collection became one of the main reasons I applied to Duke.

What interested you about the collection—why did you want to work with us?

ORION: Truth be told, before speaking with Dr. Borths, I mostly only knew about Mesozoic paleobiology (i.e., the time of the dinosaurs). Our conversation gave me an appreciation for mammal paleobiology that has grown since then. I was particularly interested in the collection’s fossils from organisms that went extinct very recently, such as giant lemurs. It’s mind-blowing to think that such giant mammals were seen by human beings.

What is something fun you’ve learned or done in your time working with us so far?

ORION: I’ve done a fair amount of work photographing fossil hyrax jaws. Along the way, I’ve learned a lot about mammal dentition more broadly. I’m fascinated by the amount of dietary detail that can now be revealed by teeth alone. And I’m very excited to see what conclusion will ultimately be drawn from the data!

How might working with fossils fit into your future education and career goals?

ORION: I may try to pursue a career in paleontology or an adjacent career in evolutionary biology. I’ve always been drawn to paleontology because of the horizons it opens up; when I think that there have been millions of biospheres as complex and interesting as our current biosphere, I feel like I’m on the edge of something truly vast. In addition to helping others with their research, this work at the DLCMNH gives me the opportunity to learn first-hand what it’s like to explore these horizons.

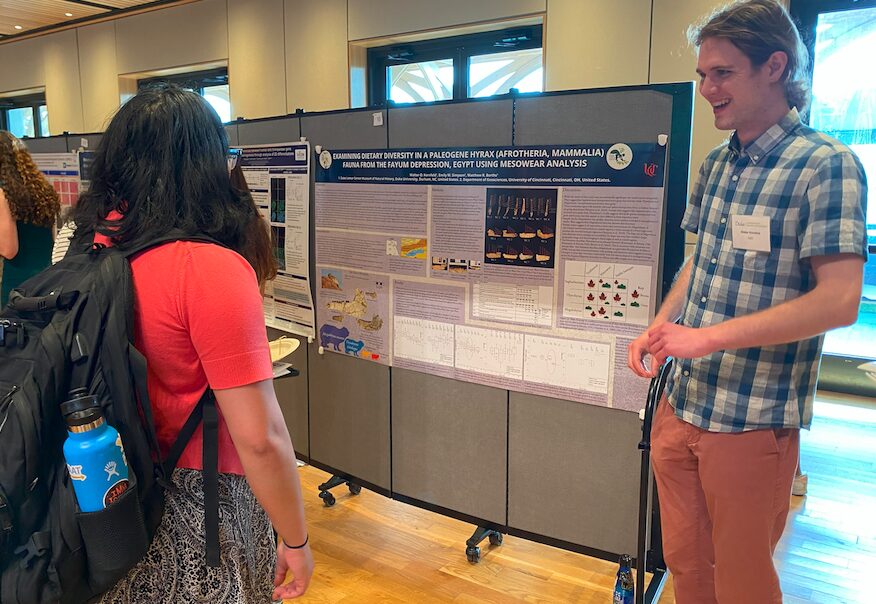

Undergraduate Orion Kornfeld presents his hyrax research at the Duke Research Forum.