By Stephen Schramm. Originally posted in DukeTODAY on February 25, 2019: https://today.duke.edu/2019/02/blue-devil-week-protecting-priceless.

Name: Greg Dye

Title: Executive Director, Duke Lemur Center

Years at Duke: 11

What he does: In 2005, Dye, who had spent two decades working with dolphins, walruses and killer whales in aquariums, moved with his family to North Carolina, where he started a consulting business for zoos and aquariums with his wife Meg.

One of their first clients was the Duke Lemur Center. When he visited the facility, which cares for North America’s largest group of lemurs – all of which are endangered – he was enchanted by the lemurs, the facilities and the center’s dedicated staff.

“From day one, it always just struck a chord that this place is such a gem,” said Dye, who will assume the role of the center’s executive director in July. “You just don’t find facilities like this out there.”

It was a thrill when, a few years later, Dye joined the staff as the Director of Operations and Administration.

“It’s been an opportunity of a lifetime professionally speaking,” Dye said. “There is nowhere else in world where this type of research, conservation and educational programming exist in one place. The size and diversity of the colony of lemurs living at Duke exists nowhere else in the world outside of Madagascar. We are one of Duke’s unique assets.”

As executive director, Dye handles a wide range of duties, ranging from ensuring the business operations of the center are sound to overseeing the care of the lemur population.

“The biggest responsibility I have is making sure the animals are cared for and safe every single day that we’re here,” Dye said. “This is one of the most endangered collections anywhere in the world. That is not lost on me. But whether they’re endangered or not, we have a responsibility to provide the best care possible.”

What he loves about Duke: From his committed colleagues at the Lemur Center to others from around Duke, Dye said there’s never a shortage of smart and motivated co-workers ready to help. For proof, he mentions the staff members of Duke Facilities Management, who spring into action when there’s an issue with one of the center’s buildings. Or he mentions the staff members at the Innovation Co-Lab who recently helped 3-D print custom pieces for cages doors and a 3-D cast of an aye-aye’s jaw to allow the Lemur Center’s veterinarians to better visualize and treat a tooth abscess.

“I can pick up the phone if I have a problem and I will find somebody at Duke who will be willing to help me,” Dye said. “I still reach out to members of my Duke Leadership Academy cohort (class of 2013) on a regular basis for advice, especially when I find myself struggling with a challenge. I love that teamwork is firmly entrenched in the culture of the Lemur Center and Duke.”

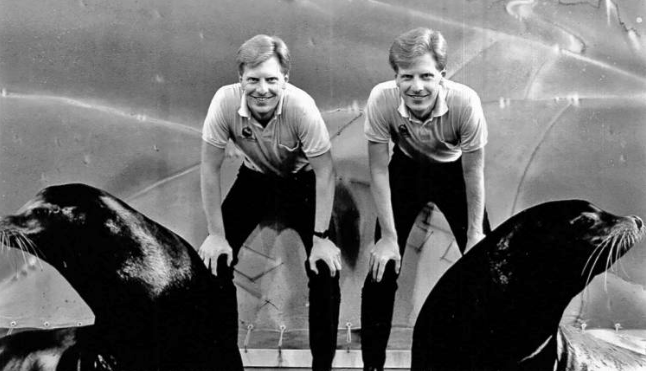

Greg Dye, right, and his brother Craig, pose with sea lions during their time working as trainers at SeaWorld.

Meaningful object in his workspace: On the shelves of his office, Dye has photos of his family members, including multiple photos of his three daughters and one picture with his brother, Craig. The photo of his brother is notable because he’s an identical twin.

The photo of the two of them, which was taken when they were both trainers at SeaWorld, shows them posing with two sea lions – their co-stars in one of the park’s regular shows.

“They changed the show when we were working on the same day to have one of us run off the stage and have the other one appear on the other side of the stage,” Dye said.

Memorable day at work: Dye recalls the first time he walked through an enclosure at the center with a family of six sifakas nearby.

“They were jumping over our heads, they were jumping out in front of us,” Dye said. “This was years ago and I still remember it. I think of it when I go out walking through there now. I love that. You can’t do that anywhere else.”

First ever job: During summers growing up, Dye helped out at his grandfather’s dairy farm in northeast Ohio. He said it was an enjoyable and formative experience.

“We’d get up there early, at 6 in the morning and work until 7 at night, just baling hay and milking cows,” Dye said. “I loved it. That was where I first learned what a true work ethic was. There was no phoning it in. You had to show up and do your part, otherwise the team didn’t get done what it needed to.”

Best advice ever received: Early on in his career, Dye was working at Chicago’s Shedd Aquarium when his supervisor, Ken Ramirez provided some sage advice.

“I remember him telling me that you always have to keep learning,” Dye said. “If you ever get to where you feel like you’ve learned it all, you’ve got to quit. I remember early on, being a young trainer, I kind of got it. But it wasn’t until later, when I’d made the decision to come to the Duke Lemur Center, that I really understood it.”

Dye said that embracing the concept of always having a receptive mind helped him adjust to working with lemurs after a career spent caring for aquatic species.

“I was learning a whole new taxa of animals,” Dye said. “If you’d told me a couple of years earlier that I’d be working with a colony of primates, I would have said you’re nuts. But life takes you all sorts of places, so you just have to be open to learning.”

Something that most people don’t know about him: Around 1991, while working at the Shedd Aquarium, Dye was joined at work for a week by a pair of writers of Harlequin romance novels.

“They wanted to do a book about a love affair between an animal rights activist and a dolphin trainer,” Dye said. “I don’t know how they got paired up with me.”

Dye, who was in his early 20s, showed the writers what he did while they peppered him with questions ranging from the simple “What are you doing now?” to the more complicated “How would you feel if your girlfriend was an animal rights activist who was only dating you to get information?”

“I just remember it being so surreal,” Dye said. “It was just so bizarre.”

About a year later, Dye received a copy of the book. While he’s never gotten around to reading it, his wife has.

“She got a kick out of it,” Dye said. “I should probably go dig it out and read it.”