Ecology and conservation of lemurs in the COMATSA protected area and importance of the corridor for threatened species

Rabevao Edgar (1), Nivolala Audon (1), Tsilanizara Jean Eric (2), Aldo Bezara (2), Rasoamiadana Louisène Olina (2), Dimbiarijaonina Candidier (2), Njakandrina Jeantauné (3), Be Monique Suzanne (3), Feno Telesy (3), Andrianasy Jean (4), Zerimanana (5), Rasolofo (5), Tiamanana Jean (5), Rabearison Jacquit (5), Ramalazamanana Hilariot (6), Jerimanana Felix (6), Velomanana Ramarotombo (6), Rasolomon Flavien (6), Razafimamonjy Victorien (6), Rabemanana Stéphan (7), Ramananjara Fredeau (7), Fidizara Jean Gicheux (7), Razanamanga Bernadette (7), Ramaroson Zafindravelo Jean Omer (7)

1: Teachers at the SAVA Regional University Center (CURSA), Antalaha, 2: CURSA Graduate Students, 3: Master students in the Faculty of Science of the University of Antsiranana, 4: Lemur researcher at Marojejy National Park, specialist in Propithecus candidus, 5: Community Patrollers (COBA) in Site 1, 6: Community Patrollers (COBA) in Site 2, 7: Community Patrollers (COBA) in Site 3

INTRODUCTION

Madagascar is known worldwide for its biological and ecological riches. Lemurs are endemic to Madagascar and are the most endangered mammals in the world. Out of approximately 112 species and subspecies of lemurs, 90% are Endangered. Lemurs form an emblematic group for the conservation of Malagasy nature and their conservation is a global priority.

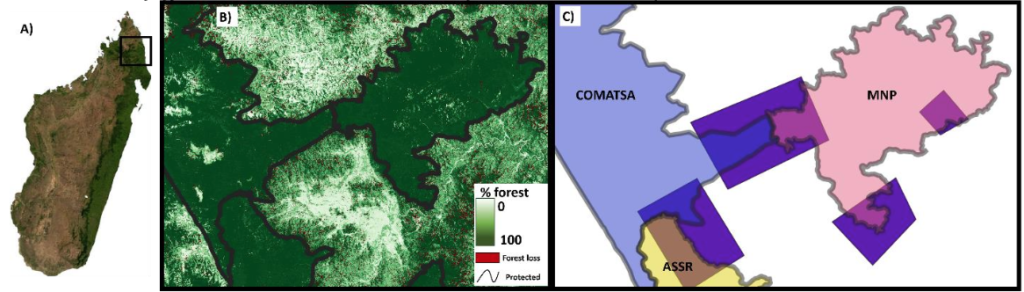

The COMATSA protected area and the connected national parks and reserves constitute the second-largest terrestrial protected area network in Madagascar (Figure 1). It was created in 2015 and plays an important role in the connectivity between Marojejy National Park, Anjanaharibe Sud Special Reserve, and Tsaratanana Strict Nature Reserve. It is a biological bridge for the remaining animals and plants to disperse among these areas, and it also constitutes an important habitat for the silky sifaka, Propithecus candindus. It is home to at least 248 species of endemic vertebrates, 80 of which are amphibians, 52 reptiles, 79 birds, and 27 small mammals. The species of lemurs in the COMATSA protected area are represented by 4 families, 8 genera, and 11 species. The silky sifaka is an emblematic and endemic species for COMATSA, and a flagship species for the SAVA region.

The critically endangered silky sifaka is only found in the northeast of Madagascar, and the COMATSA is an important corridor that unites populations across their range. Photo by Laura De Ara.

Figure 1. Map of COMATSA and connected protected areas in northeast Madagascar. A) the region within Madagascar, B) the forest cover in the study region based on satellite imagery from 2017, and C) highlighted areas show the current and proposed comparative study sites. MNP = Marojejy National Park, ASSR = Anjanaharibe-Sud Special Reserve.

One of the greatest threats to biodiversity is habitat loss, degradation, and fragmentation. Madagascar lost 44% of its natural forest cover between the years 1950 and 2014. The destruction of the COMATSA corridor would lead to the isolation of these adjacent protected areas, decrease habitat for groups, and promote inbreeding. Hunting in the COMATSA disrupts ecological processes, due to changes in the composition of animal communities and a likely decrease in biological diversity. It is, therefore, crucial to protect this important corridor.

The silky sifaka is one of the rarest primates in the world and is among the 25 critically endangered species of lemurs with a population of fewer than 250 individuals remaining in the wild. Its distribution is confined to mostly the SAVA region, such as Marojejy, Anjanaharibe Sud, COMATSA, and Makira in mountain habitats up to 1875 m elevation. The loss of its habitat due to clearing land for agriculture, selective cutting of precious woods, as well as hunting for local consumption even in protected areas are the major factors in the decline of the population of silky sifakas and other species as well. No traditional prohibition (taboo or fady) has been observed on the consumption of this species.

Our overall objective in this project is to determine the viability and sustainability of lemur populations and their ecosystems in COMATSA. To achieve this overall objective, we are studying the abundance and diversity of lemurs in the corridor, assessing the habitat quality throughout the lemurs’ ranges, quantifying pressures and threats to lemurs and their habitats (hunting, clearing, logging, mining), and establishing participatory community-based hunting management structures and promote alternatives to the sustainable use of natural resources.

The hairy-eared dwarf lemur is one of the rare species found in COMATSA. Active at night, this species has been difficult to study and the COMATSA may be an important refuge for their conservation.

PRELIMINARY RESULTS

Lemurs

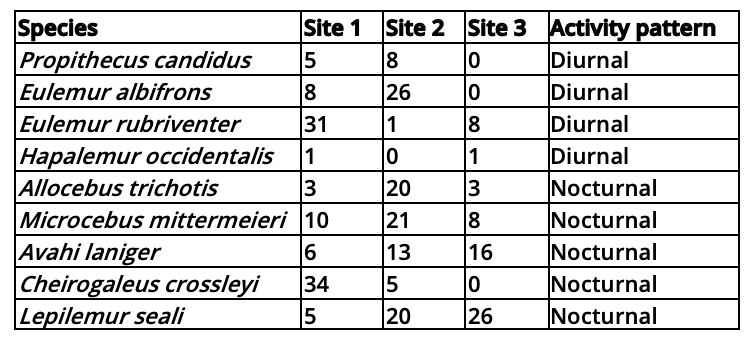

During our missions to three sites, 10 species of lemurs were inventoried, including four diurnal species such as silky sifaka (Propithecus candidus), white-fronted brown lemurs (Eulemur albifrons), red-bellied lemurs (Eulemur rubriventer), and bamboo lemurs (Hapalemur occidentalis). There were also seven nocturnal species including the woolly lemur (Avahi laniger), dwarf lemurs (Cheirogaleus crossleyi), hairy eared dwarf lemurs (Allocebus trichotis), mouse lemurs (Microcebus sp. cf. lehilahytsara/mittermeieri), sportive lemurs (Lepilemur seali), and aye ayes (Daubentonia madagascariensis, feeding traces observed). The frequency of observing these lemurs varied across sites and species (Table 1).

Table 1: Frequency of observations on nine lemur species at three sites during 15 days per site.

Habitats

During the floristic inventory of lemur habitats, 240 plant species belonging to 83 families were identified. These species are dominated by Coffea sp (resinosa/buxifolia) which belongs to the family of Rubiacées. Other dominant species include Ocotea, Noronhia, Syzygium, and Garcinia, which are all important lemur food trees.

Pressures and threats

Threats to forests and lemurs include making charcoal, artisanal mining, selective logging, lemur hunting especially with traps, human settlements, and deforestation by shifting agriculture for crops such as rice, maize, vanilla, banana, sugarcane, taro, and even illegal marijuana.

Large trees cut to make planks in the forest.

Focus groups and public outreach

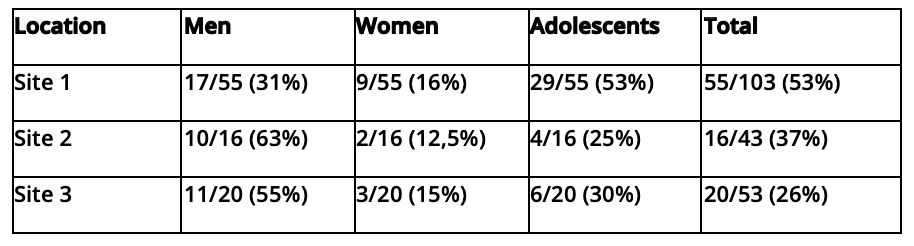

To learn more about local behaviors related to hunting wild animals, including lemurs, and the use of natural resources in these sites, we conducted focus groups with participants and discussions of the local laws. We discussed the participants’ ideas about alternative solutions related to logging and hunting. Participants were divided into 3 groups, including groups of men, women, and adolescents.

During our surveys at three sites, 244 groups of 1,599 participants were interviewed. In general, hunting was relatively common (more than 90% of focus groups in Site 1), especially for small mammals such as tenrecs and lemurs (Table 2). Arrows, guns, dogs, poison, and traps are weapons used by hunters.

At Site 1, almost 90% (103/115) of focus groups reported hunting mammals, of which 55 groups reported hunting lemurs and 92 groups hunting tenrecs. Groups of children and adolescents proved a high rate of lemur hunting (29/55) while groups of women had the lowest rate of hunting (9/55). At Site 2, 81% (43/53) of groups reported hunting mammals, with 16 groups hunting lemurs, and 40 hunting tenrecs. At Site 3, 68% (53/78) of focus groups reported hunting mammals, of which 20 groups hunted lemurs and 48 hunted tenrecs. At all sites, men’s focus groups reported the highest rate on lemur hunting, and women’s groups reported the lowest rate.

Olina conducts focus groups with women to learn about hunting and natural resources.

Table 2. Number of focus groups reporting hunting for lemurs in the three sites.

During all missions, our social survey team also conducted public outreach about lemurs and biodiversity conservation. This included lessons given in the schools during which educational posters and infographics were explained and hung at the schools, and children used coloring and activity books to create their own posters. In each village, our team screened educational films for 12 consecutive days, focusing on improved forms of agriculture like agroecology and fish farming, as well as about lemurs and biodiversity conservation. The number of participants varied between 260-400 at each site. Participants reported that improved poultry husbandry and fish farming are the alternative solutions to hunting they envision for sustainable future livelihoods.

Public outreach with school children, teaching about lemurs and biodiversity conservation. Children use coloring and activity books for interactive engagement with the learning objectives.

CONCLUSION

The COMATSA protected area in the SAVA region is home to rich fauna and flora, including the endemic lemurs. During the monitoring of lemurs at three sites, 10 lemur species were inventoried. The floral species richness in lemur habitats was also high, with over 240 tree species, and abundant lemur food trees. Despite the importance of this area for lemurs, we found evidence for high pressure on natural resources, including many areas that were logged for timber, cleared for agriculture, and where lemur traps were set.

During the focus groups in three sites, 244 groups of 1599 participants were interviewed about their hunting traditions. We learned that hunting is an important mode of acquiring meat for these communities, especially tenrecs, but with a high prevalence of lemur hunting as well. Participants reported that if lemurs or other wild animals were to disappear, alternative meat sources would include poultry and fish. Domestic animal husbandry is an important solution to issues of malnutrition and hunting in Madagascar, but unfortunately, many farmers are not trained in proper management. The respondents requested formal training in poultry and fish farming, and are seeking future collaborations with us to develop sustainability action plans. We will continue to monitor the lemurs at these and other sites, as well as partner with the communities to co-create action plans that will decrease pressure on natural resources as well as meet the needs of local people.

We are extremely grateful to the funding sources that make this work possible, especially the Knox family and a grant from Re:wild. We could not do this conservation work without your support! We are also seeking funds to support the development of sustainable alternatives like poultry and fish farming. Find more information on the DLC Targeted Impacts page.