The Duke Lemur Center is home to the largest population of living lemurs outside of Madagascar. Did you know it is also home to over 35,000 fossil specimens, including the largest fossil primate collection in North America?

Researchers from around the world study Duke Lemur Center fossils, learning more about the ancient environments that shaped lemurs and their distant primate cousins: humans! By studying the extinction of primates in the past, we are working to prevent primate extinctions in the present. We are also delving into the biology of ancient primates to learn when and where key primate traits – like big brains, social complexity, and grasping hands – first appeared.

Unfortunately, some of our most important fossils are extremely delicate. They were fossilized with salt and sulfur, which can cause the fossils to crumble unexpectedly, especially when temperature and humidity fluctuate…and we have a lot of temperature and humidity fluctuation in Durham, NC.

(Click here to watch a video of paleontologist Dr. Matt Borths, curator of the DLC’s fossil collection, explaining why fossils deteriorate — and how YOU can help!)

We have a space in the fossil lab that we try to keep at a constant temperature and humidity to stabilize the fossils when they begin to deteriorate. Duke facilities has worked with us to design an updated fossil room, which includes a special HVAC attachment that will keep the room stable. The attachment and installation total $9,200. We’ve already raised $1,500 (thank you, donors!), but we still have $7,700 to go.

From now through 12/31/2019, all donations made via this link and/or the “DONATE” buttons at the top and bottom of this page will go towards this stabilization room — a kind of “fossil ICU” that will protect these delicate fossils for decades to come while we work with paleontologists and geochemists to find the best way to preserve this unique and irreplaceable collection. All donations are tax deductible.

The fossil lab staff includes researchers dedicated to preserving the fossils. We are collecting 3D x-rays called microCT scans that can be used to make 3D digital models of the fossils. Researchers and students can study these digital models without handling the delicate specimens. The digital museum is available to anyone with an internet connection at the Duke Library-supported website MorphoSource.

The DLC fossil collection helps researchers understand extinction in the past so we can prevent extinction in the present. There are still new species waiting to be described in the fossil collection. There are so many reasons preserve them for future researchers, students, and visitors!

Help us protect the primate fossil record this #GivingTuesday!

The Duke Lemur Center is home to aye-ayes. Some very cute baby aye-ayes and some very smart adult aye-ayes, but did you know we are also home to the oldest aye-ayes? As in, 34-million-year-old aye-ayes?

Plesiopithecus (the jaw and snout) was discovered by Duke Lemur Center researchers at Quarry L-41 in the Fayum Depression of Egypt. L-41 is one of the most fossil-rich places in Africa. It preserves small, delicate fossils. The fossils of Plesiopithecus were discovered decades ago, but were only recognized as aye-aye evidence three years ago. There are so many more discoveries waiting to be made in the L-41 collection!

Unfortunately, the rocks at L-41 are saturated with salt, making them very unstable in changing temperatures and humidity. We are working quickly to stabilize and protect the unique, irreplaceable L-41 fossils, and you can help! Your #GivingTuesday gift goes directly towards transforming the room for the L-41 collection into a fossil ICU where we can keep the specimens safe for future discoveries.

We also have subfossils of much more recent aye-ayes from Madagascar. These 600 year old specimens reveal the diversity and ecology of aye-ayes as the human population expanded on the island and agriculture spread. These ancient bones are helping Duke Lemur Center researchers understand the changing Malagasy ecosystem as humans continue to impact aye-aye habitats. There are still important discoveries to made in the drawers and in the field!

The Duke Lemur Center is one of the only places in the world with living lemurs and their ancient relatives in the same place. Researchers and students can travel through millions of years of adaptation, diversification, and extinction without leaving the DLC. Today for #GivingTuesday you can help make sure the fossil history of lemurs is preserved for decades to come.

Some of the oldest lemur relatives actually come from North America! Notharctus and its relatives lived on the northern continents before hopping across the ancient Mediterranean to the island-continent of Africa. There, lemur-like primates like Aframonius scrambled through the trees next to the ancient relatives of monkeys.

Aframonius comes from Quarry L-41, one of the most fossil-rich sites in Africa, and the DLC collection is the only L-41 collection outside of Egypt. The delicate fossils of Aframonius were preserved in the fine mudstone of L-41 along with salt, which can expand and flow, damaging these ancient lemur specimens. We want to build a fossil ICU to stabilize the temperature and humidity around the L-41 collection.

If you can help us stabilize the collection, generations of visitors, researchers, and students will be able to study why most lemur-like primates went extinct in Africa, but survived in Madagascar. These insights could help us save lemurs from going extinct in Madagascar, too.

Help us preserve the fossil heritage of lemurs and humans for #GivingTuesday. Some of our fossils are literally crumbing to dust. We have a highly skilled team working to protect the collection, but we need your help, too.

One reason we study lemurs is to learn more about ourselves. Lemurs and humans are primates separated by millions of years of change. We both have pretty big brains, complex social lives, and agile hands. What we learn about lemur behavior, vision, guts, and life-history can help us explore those traits in us.

When our lemur-based observations are combined with the fossil record, we can glimpse when and where key primate traits appeared…assuming we the fossil survive long enough to be studied.

Unfortunately, some of the fossils at the Duke Lemur Center have salt and sulfur in them, making them very unstable. Some, like the specimen in the box, spontaneously break down. We have scans and photos of this specimen when it was intact only a year ago.

Your donation today will help us create a stable fossil ICU where we can ensure fossils are safe while we work to document and preserve them for future generations. We are also protecting the fossils for you to visit when we finally open fossil exhibit space at the Duke Lemur Center!

This #GivingTuesday help us preserve and protect some of the weirdos in your family tree!

On the left is the skeleton of Paleopropithecus, a giant sloth LEMUR from Madagascar! This crazy creature only went extinct a few centuries ago. Its closest living relatives at the Duke Lemur Center are sifaka, which also like to hang around upside down.

At the Duke Lemur Center, researchers study the locomotion of sifaka and Paleopropithecus, comparing their anatomy to understand the diversity and ecology of this fascinating family of lemurs. Unfortunately, some of our fossils are unstable in the changing temperature and humidity of North Carolina. Your donation today will help us create an insulated fossil ICU at the Duke Lemur Center that will ensure researchers, students, and visitors will be able to study the collection of over 35,000 specimens for decades to come.

Thank you so much for your support! If you have any questions, please contact our development officer, Mary Paisley, at (919) 401-7252 or mary.paisley@duke.edu. She would love to hear from you!

Learn More

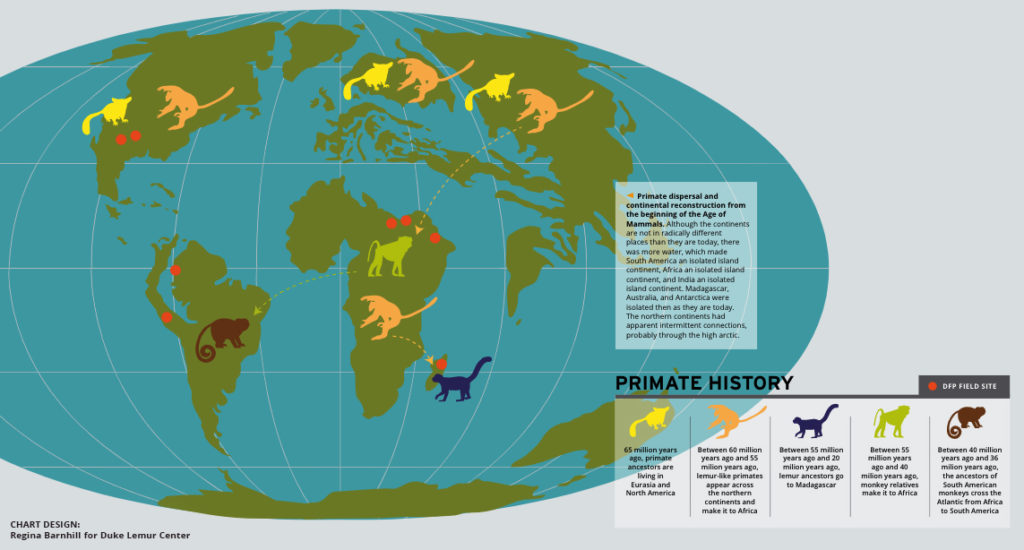

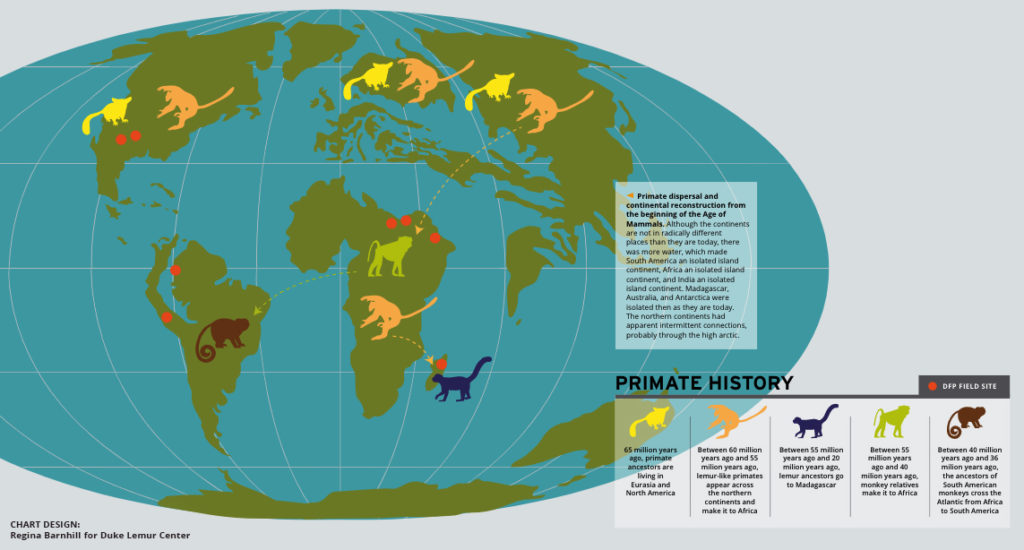

65 million years ago, soon after the extinction of the non-avian dinosaurs, the primate story was unfolding in North America. From the northern hemisphere, primates found their way to Africa, Madagascar, and South America. Sorting out how they adapted and diversified their way around the globe drives much of the research at the Division of Fossil Primates (DFP) at the Duke Lemur Center, which has field sites around the world (marked above with a red dot). Click anywhere on the image for a larger view.

The Duke Lemur Center houses more than 35,000 fossils, including one of the world’s most important collections of early anthropoid primates. These fossils help us understand our evolutionary journey as primates. Primates are the group of mammals that includes lemurs, monkeys, apes, and humans. For more than forty years, Duke scientists have conducted fieldwork around the world, targeting major branches in the primate family tree for deeper exploration. Our collection includes 55 million year-old, lemur-like primate fossils from Wyoming; 37 to 28 million year-old anthropoid fossils from Egypt; 19 to 7 million year-old ape fossils from Egypt and India; 13 million year-old New World monkeys from Colombia; and 10,000 to 500 year-old lemur fossils from Madagascar.

Because Duke paleontologists are also interested in role the ecosystem played in shaping our primate relatives, many of the 35,000+ specimens at the DLC’s fossil division also represent non-primate lineages, including bats, proboscideans (the relatives of elephants), crocodilians, birds, rodents, carnivorans, sharks, and anthracotheres.

Read more about our fossils on the Division of Fossil Primates homepage.