Madagascar is the fourth largest island in the world and features some of Earth’s most amazing and diverse biological life. Isolated for more than 80 million years, the plants and animals of Madagascar spent millions of years evolving their own unique characteristics, not to be found elsewhere on the planet. Remarkably, the more than 100 species of lemurs found in Madagascar exist naturally nowhere else on Earth. Such extreme endemism is characteristic of all forms of life on this oceanic island with 98% of the mammals, reptiles, and amphibians and over 90% of the (more than 12,000) plant species being found nowhere else on the planet.

The sheer size of Madagascar (nearly 1000 miles long and 350 miles wide) coupled with the diversity of Madagascar’s regional climates and habitats—desert, lowland and high altitude rain forest, dry deciduous forest, mountains and valleys, grasslands, spiny forest and knife-edged limestone formations—creates such a vast array of habitats for wildlife and plants that Madagascar is often referred to as the “Eighth Continent.”

Pictured: Madagascar is home to two-thirds of the world's chameleon species.

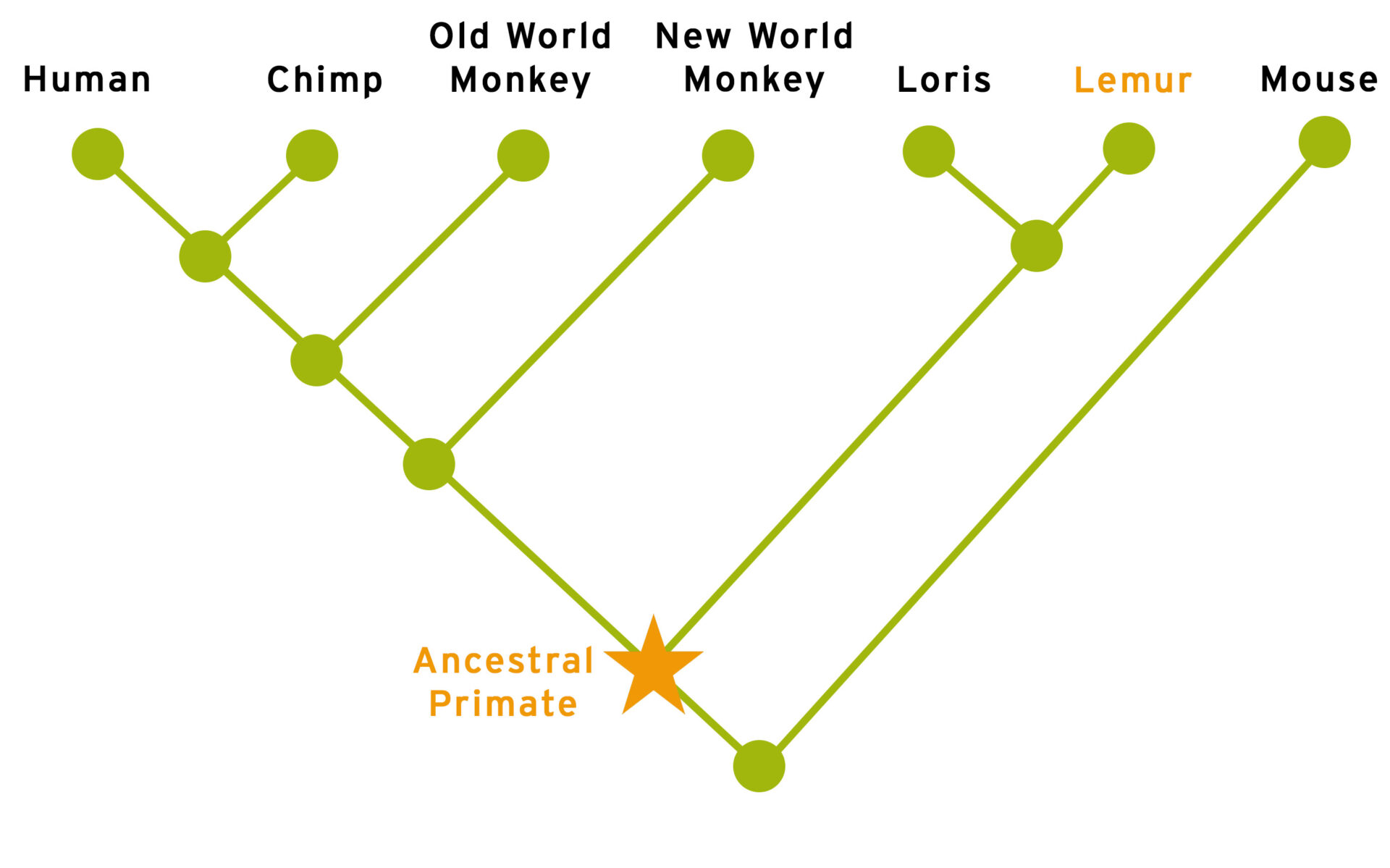

As primates, lemurs are our most distant relatives within our own family tree. Studying lemurs within a comparative context across primates allows us to understand ourselves, and the traits and processes that make us both primate and human.

Because the lineage that includes lemurs split from the monkey, ape, and human line millions of years ago, lemurs retain traits that are truly unique among today's primates – and because of their evolutionary age and incredible variety of lifestyles and adaptations, the lemur branch of the primate family tree is particularly interesting to scientists. By non-invasively studying lemurs, DLC researchers gain tremendous insight into primate evolution and human health and behavior. We share with lemurs the vast majority of our genetic code and many of the same diseases, susceptibilities, and health concerns: Studying lemurs could potentially help us find solutions to combat serious problems facing modern society.

For example, some lemur species develop the same plaques and tangles seen in the brains of humans diagnosed with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Others go into seasonal torpor, a form of hibernation, which is unique among primates. Studying these traits in lemurs provide key clues about primate evolution and also now hint at exciting scientific discoveries that will impact humans.

Since humans arrived on the island 4,000 years ago (Dewar et al. 2013), tremendous deforestation and animal extinctions have occurred. Less than 16% of Madagascar is now covered in forest, and within last 60 years, forest cover has decreased by nearly 40% (Harper et al., 2007). At least 17 species of lemurs (ranging in size from 10kg to 160kg) and many other megafauna, such as the 10-foot-tall elephant bird, have recently gone extinct. Currently, lemurs are considered the most threatened mammal group on earth (Schwitzer et al., 2014).

The island’s human population has ballooned to over 24 million, with more than three-fourths of the population living on less than $1.25 per day. People farm the land to feed their families using traditional methods of slash-and-burn agriculture, which results in loss of soil fertility, erosion, wildfires, and stream sedimentation. Ultimately, the soil is depleted and new patches of forest are burned to create more farmland, with the result that subsistence agriculture is a primary driver of forest loss. The need for land has grown exponentially with Madagascar’s population, which is expected to double by 2050; and the unique biodiversity of Madagascar continues to suffer. Conservation, as the Duke Lemur Center practices, must meet the needs of local communities in addition to protecting the amazing fauna and flora of Madagascar.

At least 17 species of lemur have gone extinct, and the existing lemurs are the most threatened group of mammals on Earth. An assessment by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2018 identified 95% of the remaining 103 lemur taxa as threatened, compared to 74% only four years prior.

It's a race against time to preserve lemur populations, and conservation programs both ex-situ (managed care/zoos) and in-situ (in the wild) are vitally needed.

Pictured: The skull of Megaladapis, an extinct giant lemur, from the collection of the DLC Museum of Natural History. Built somewhat like a koala, the slow-moving Megaladapis was approximately as large as a female gorilla. The species was alive as recently as 650 years ago.