December 17, 2013 — Caring for lemurs is more than a full time job. The Duke Lemur Center relies on a dozen trained keepers and more than 70 volunteers for everything from feeding lemurs and cleaning enclosures, to sweeping up at the end of the day. Here, we’ll introduce you to the people who work hard every day to keep the lemurs happy and healthy. Today we go behind the scenes with technician’s assistant Allison Stitt, who tells us what it’s like to do daily clean-up detail, and why it’s hard to pass as a lemur while wearing scrubs and wielding a hose:

Every Thursday starting at 8 am, I’m on a mission. That mission is not only to care for the prosimians at the Duke Lemur Center, but to be one — or at least, to convince the lemurs that I can be one of them.

This is not always easy. Clothed in blue scrubs, I don’t really fit the description of any lemur. I am a giant bumbling, blue, far-removed primate from those at DLC — and armed with a hose, I become a creature to avoid.

The ring-tailed lemurs take one look at my hose and flee to go cuddle up together somewhere. Chloris the ringtail is the only one who ever sticks around to see me cleanse her home, passively sitting back with her belly out and her head nestled into her neck. I’m guessing she’s reached the age where she’s too old to care about an invading human in her territory.

The crowned lemurs, the black lemurs, and the common brown lemurs tend to keep their distance from me as well, only these guys are a little more vocal than the ringtails. The noises they make are like little snorts, and they’ll snort snort at each other while I clean around them. I often try to talk back to them, doing my best to snort my way into their conversations (I don’t know what’s more embarrassing –- getting caught talking to the lemurs, or getting caught trying to speak lemur!).

Yet, I think my humanness is a little too apparent; they see right through my façade. Even when I think I’ve snorted the ideal lemur snort, I get a little look from one of them that’s like “Really, human? Really?”

Then one day, I was assigned to A Wing.

A Wing is where the free-ranging lemurs are. My excitement to meet the new lemurs was unparalleled. As soon as I walked in, I was met by the gazes of six fluffy primates.

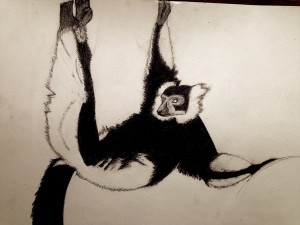

They were a species I hadn’t seen before: black and white ruffed lemurs. These guys are close in appearance to their red-ruffed cousins. I stared at them, and they looked right back at me unflinchingly, even when I opened the door and walked in with that omen of evil, the hose. They all crowded around me, and began making a noise I hadn’t yet heard from a lemur. It was kind of like an arhwooo? It sounded like a question, the way it rose in pitch at the very end.

Arhwooo? Arhwooooooo?

The black and white ruffed lemurs had a curiosity that made their inquiring noises seem appropriate. I stood motionless, while they crawled on the fenced walls around me. I had my head sniffed, my name-tag grabbed, my hair nibbled on, and my legs probed by little lemur hands. Each little touch was startling; it’s not like having a cat or dog put their paws on you, since lemurs have fingers very like ours.

Whenever I go in to clean for these guys now, they follow me around from room to room doing their stunts andarhooo?-ing. I never had them fooled about my non-Malagasy roots, but I like to think of myself as an honorary lemur anyway.

(And I’m still going to keep practicing my lemur calls just in case.)

Allison Stitt is a Technician’s Assistant at the Duke Lemur Center and a Psychology major at UNC Chapel Hill.

Allison Stitt is a Technician’s Assistant at the Duke Lemur Center and a Psychology major at UNC Chapel Hill.