Welcome!

Welcome to page two of 100 LEMURS, an international collaboration between the Duke Lemur Center, a world leader in the study, care, and conservation of lemurs, and Rachel Hudson, an award-winning wildlife illustrator based in the UK!

To return to page one and to view our first 14 featured species, please click here.

Day thirty-one

Today we’re featuring the rare Sahamalaza sportive lemur (Lepilemur sahamalazensis)!

These small, solitary, nocturnal lemurs are found in only one location in Madagascar: the Sahamalaza Pensinsula along the northwestern coast, a habitat it shares with the critically endangered blue-eyed black lemur. Due to their narrow geographic range, both species face extreme pressure from habitat loss, forest fragmentation, and hunting.

The Sahamalaza sportive lemur is classified as Critically Endangered by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). In 2007, it was estimated that only 3,000 of these sportive lemurs remain, making it one of the most endangered species of lemur. It was also placed on the list of the world’s 25 Most Endangered Primates 2006-2008.

Day thirty-two

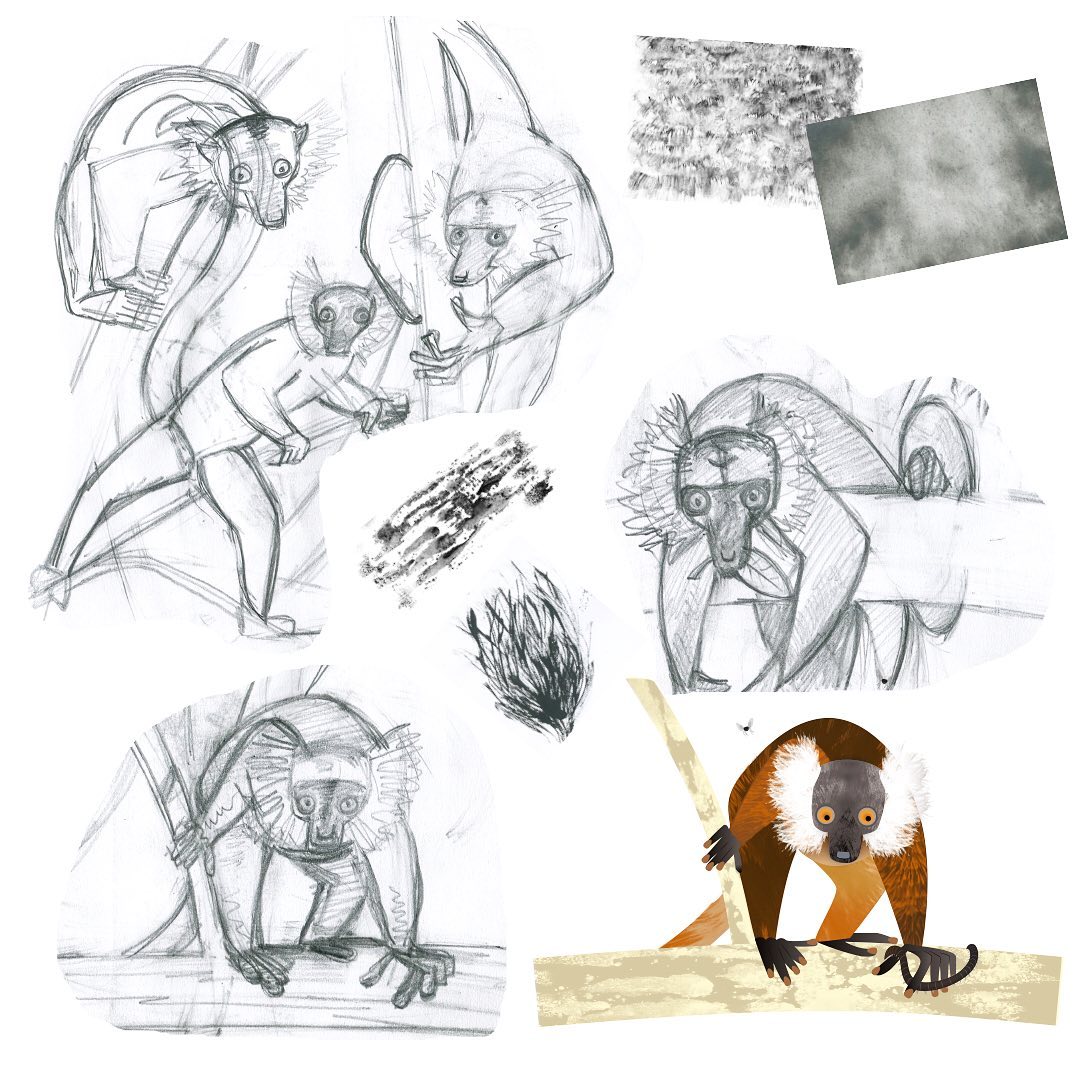

Here’s a sneaky peek behind the scenes!

Thanks so much for joining us every day to discover more about the world of lemurs. Your likes and comments are very much appreciated — please keep them coming! We hope you are falling even more in love with these incredible, endangered animals. They need champions in order to survive.

Still to come are... mouse lemurs, fork-marked lemurs, ruffed lemurs, sifakas, bamboo lemurs, extinct giant lemurs, and lemurs’ ancestors. Did we mention that all next week will be dedicated to ring-tailed lemurs…?!

Several people have asked how Rachel creates her illustrations, so today, we’re taking you behind the scenes by sharing a few process drawings and textures!

1) Each illustration starts with research. Rachel’s current bedside reading: Conservation International’s Tropical Field Guide to Lemurs of Madagascar!

2) She then make lots of scruffy pencil sketches to work out the best composition/shapes that capture characteristic movement and behavior.

3) Then she uses her messy workbench to create prints, paintings, and inky marks for the underlying textures (for fur, tree bark, etc). This helps to add depth and interest.

4) Lastly, she uses a cintiq pro drawing pad and her pc to bring everything together and edit the illustration. Some species are easier than others!

Day thirty-three

Check out the weasel sportive lemur (Lepilemur mustelinus) in BOTH color variations!

At home in the rainforests of eastern Madagascar, this relatively large (1kg) sportive lemur can be found in Analamazoatra Special Reserve and Andasibe-Mantadia National Park alongside the famous diademed sifaka (Propithecus diadema) and the iconic indri (Indri indri).

Most weasel sportive lemurs have chestnut brown body fur, but some bright orange individuals have also been observed.

This nocturnal, solitary lemur shelters in tree holes or tangles of vines and leaves during the day and forages for leaves, flowers, and fruits at night.

Occassionally mistaken for the dwarf lemur lemur, the weasel sportive lemur can be distinguished by its larger size, leaping, and vertical posture (whereas the dwarf lemur moves quadripedally).

Day thirty-four

Meet the white-footed sportive lemur (Lepilemur leucopus) with special guest — the Madagascar fruit bat (Pteropus rufus)! Can’t spot the lemur in the image? Click the picture for a larger view!

One of the smallest sportive lemurs, the white-footed sportive lemur weighs just 500-700g.

It has been most studied in Berenty Reserve in southern Madagascar, a private reserve famous for its troops of ring-tailed lemurs and “dancing” white sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi).

During the day, male and female white-footed sportive lemurs sleep separately or together in tree holes or tangles of woody vines. At night, they’re active alongside other nocturnal lemurs – the mouse lemurs and dwarf lemurs – as well as native owls and the south’s largest colony of Madagascar fruit bats. These bats are among the largest in the world, with wingspans of over one meter!

Day thirty-five

It’s ring-tailed lemur week! Today we’re thrilled to introduce you to this Malagasy icon!

The iconic ring-tailed lemur (Lemur catta), named after its long black and white “ringed” tail, is one of the most recognizable lemur species.

Ring-tails are the most terrestrial lemurs, spending up to 50% of their time on the ground (as opposed to high in the trees) – more than any other lemur species.

Led by a single dominant female, troops can be up to 30 individuals. To keep such a large group together when traveling on the ground, individuals’ tails are held high like flags.

As opportunistic omnivores, ring-tails are among the most carnivorous lemurs and will eat anything from fruit, flowers, and leaves to insects and even (rarely) small birds and chameleons!

If you’d like to learn more about ring-tails while supporting their care at the DLC and their conservation in Madagascar, please consider symbolically adopting Teres, a male ring-tailed lemur, through our Adopt a Lemur Program!

Day thirty-six

Day thirty-six of #100lemurs, and our second day of Ring-tailed Lemur Week! Today we’re highlighting female dominance.

Ring-tailed lemurs are naturally social. They live in big groups (up to 30 individuals) of multiple adult females and males and offspring of various ages. In such a large group, clear social structure helps things run smoothly.

In ring-tailed lemur societies, female dominance is the natural law of the land! All females outrank all males. It’s not uncommon for females to shove males out of their way and steal their food or nap spots. If males don’t follow suit, the females aren’t afraid to get physical.

Females also physically compete for dominance among themselves. In general, the higher your dominance rank, the more food you get, which promotes your health and reproductive success.

With all that said, ring-tailed lemurs absolutely have a gentler side and engage in ‘nice’ behaviors that promote social bonding, including grooming, huddling, play, and hanging out.

Day thirty-seven

Day 3 of Ring-tailed Lemur Week features social grooming!

Within a family group, lemurs can often be found combing through each other’s fur! With the exception of the aye-aye, lemurs’ bottom teeth form a special “toothcomb” structure, which they use for grooming themselves and other lemurs.

Grooming is an instinctive social behaviour that is not just hygienic, but also strengthens the social bonds within the group.

Why a toothcomb? Lemurs lack the manual dexterity of monkeys and apes, which is why they aren’t effective at grooming with their fingers. Most lemurs have flat fingers and short fingernails, with the exception of the second toe on each foot, which has a sharp pointed grooming claw.

Day thirty-eight

Day 4 of Ring-tailed Lemur Week — let’s learn about sun worshipping!

Ring-tailed lemurs (as well as ruffed lemurs and sifakas) will gather in open areas of the forest to sunbathe.

They sit in what some call a “yoga position” with their bellies toward the sun and their arms and legs stretched out to the sides.

This position maximizes the exposure to the less densely covered underside of the lemurs to the sun, warming them up before they forage.

Day thirty-nine

Day 5 of Ring-tailed Lemur Week, and today we’re highlighting diet and feeding behavior!

Ring-tailed lemurs are hardy omnivores and are adaptable to many foods – they have even been seen eating chameleons! Lizard-eating appears rare, however, and often their diets consist of fruit (unripe and ripe, depending on season) and leaves (both mature leaves and young leaves).

In harsher seasons, tamarind becomes a key fallback food for ring-tails, who can eat the unripe pods and mature leaves.

There are reports of ring-tails occasionally eating many, many other food items, including flowers, seeds, spiders, caterpillars, sandy earth and soil. After a bad cyclone, catta were also observed crop-raiding sweet potatoes from nearby farms. These lemurs truly are flexible feeders!

Day forty

Day 6 of Ring-tailed Lemur Week, and Rachel has illustrated a fascinating behavior indeed: stink fighting!

One of the ways a male ring-tailed lemur competes with other males is by stink fighting. To prepare, each male rubs his tail with scent from his wrist glands. He can include scents from his shoulder gland, too: Whereas the wrist glands produce a light and airy liquid that acts as a special ‘eau de lemur toilette,’ the shoulder glands produce a thick, dark secretion that might act as a glue to create longer-lasting scents.

After each lemur has anointed his tail with these smelly secretions, both rivals wave their tails in the air, wafting their “fragrance” toward one another. If stink fighting doesn’t solve their dispute, males will get physical, especially in the breeding season, as they vie for attention and breeding opportunity.

Day forty-one

It’s the last day of Ring-tailed Lemur Week. Let’s talk about scent marking!

Whereas male ring-tailed lemurs have multiple scent glands, females have just one scent gland, which is located in the genital area. Swipe left to see a female ring-tailed lemur scent-marking a tree.

According to Duke University researcher Christine Drea, each lemur’s scent contains hundreds of “different chemical compounds in a complex mix that has been found to vary not only by season, but by an individual’s genetics as well.” The scent can even change when a lemur is ill or socially stressed.

In addition, a female ring-tails’ scent is more complex than the males’. Via scent, females may advertise not only their fertility, but also the presence of a pregnancy, how far along it is, and whether she’s carrying baby boys or baby girls! How cool is that?!

Day forty-two

While “giant” and “mouse” may be an oxymoron, northern giant mouse lemurs (Mirza zaza) are three times larger than other mouse lemurs.

While their bodies are small, weighing around 11 ounces, the males of this species have the largest testes- to- body ratio of all primates. Way to go, boys!

The females mate with multiple males and, unlike other lemurs, mate throughout the year rather than seasonally.

While northern giant mouse lemurs forage alone at night, they sleep in communal sleeping nests during the day with two to eight unrelated individuals. They also have been recorded working together to harass and chase off snakes that could prey on these small nocturnal primates.

Day forty-three

Yesterday we highlighted the biggest of the mouse lemurs; today we’re featuring Madame Berthe’s mouse lemur (Microcebus berthae) — the smallest of the small! At only 30 grams (1 ounce), this mouse lemur is the world’s smallest primate.

Their range is a small section of deciduous forest in western Madagascar where they coexist with gray mouse lemurs who are twice their size.

Luckily, the feeding strategies of these species are different enough that they do not seem to be major competitors for each other. Madame Berthe’s mouse lemurs specialize on insect secretions with some insect prey as well. Gray mouse lemurs are more opportunistic, eating fruit, flowers, and gum as well as insects.

Day forty-four

Here’s a species dear to our hearts here at the DLC: Meet the grey mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus)!

The grey mouse lemur is famously flexible and resilient. For a mouse lemur, this species is medium-sized with big ears and grey fur. They are widely distributed, inhabiting nearly every dry forest in western Madagascar.

Grey mouse lemurs are true omnivores, eating various insects, fruits, flowers, tree exudates, and even frogs and geckos.

Some enter hibernation each year, whereas others remain active year-round.

Females can produce a single litter per year, or they can have two or three. Unusual for mouse lemurs, related females of this species can sleep together in tree holes during the day, whereas males remain bachelors. Really, in grey mouse lemurs, anything goes!

If you’d like to learn more about mouse lemurs while supporting their care at the DLC and their conservation in Madagascar, please consider symbolically adopting Thistle, a female gray mouse lemur, through our Adopt a Lemur Program!

Day forty-five

Weighing just 45g, Goodman’s mouse lemur (Microcebus lehilahytsara) is one of the smaller mouse lemurs and looks very much like its cousin, Microcebus rufus.

In fact, if you think many of the mouse lemur species look similar to each other, you’re not alone! Just two decades ago, only two species of mouse lemur were recognized (the reddish-brown ones and the gray ones). The genetics revolution, however, revealed major variation in the mouse lemurs’ genomes — enough to split them in 24 species!

Much of this genetic variation isn’t visible when simply looking at the different species: It just doesn’t make a whole lot of sense to be visually distinct in a nocturnal world. In biology, we call this phenomenon cryptic speciation.

Click here to continue to page four (species 46-60)!