The Duke Lemur Center recognizes that our work to protect lemurs here at Duke University and in cooperation with other AZA (Association of Zoos and Aquariums) accredited organizations is not enough: we must also take action to protect lemurs in their natural habitat in Madagascar.

For 35 years, we’re proud to work with the organizations and people of Madagascar to create opportunities for positive change, and to play a leading role in preventing the island’s legendary population of endemic and endangered species from being lost forever.

The DLC’s conservation projects in Madagascar are run exclusively on grants and donor funding. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation today.

Why lemurs and Madagascar matter

Madagascar is a rare biodiversity treasure

Madagascar is the fourth largest island in the world and features some of Earth’s most amazing and diverse biological life. Isolated for more than 80 million years, the plants and animals of Madagascar spent millions of years evolving their own unique characteristics, not to be found elsewhere on the planet. Remarkably, the more than 100 species of lemurs found in Madagascar exist naturally nowhere else on Earth. Such extreme endemism is characteristic of all forms of life on this oceanic island with 98% of the mammals, reptiles, and amphibians and over 90% of the (more than 12,000) plant species being found nowhere else on the planet.

The sheer size of Madagascar (nearly 1000 miles long and 350 miles wide) coupled with the diversity of Madagascar’s regional climates and habitats—desert, lowland and high altitude rain forest, dry deciduous forest, mountains and valleys, grasslands, spiny forest and knife-edged limestone formations—creates such a vast array of habitats for wildlife and plants that Madagascar is often referred to as the “Eighth Continent.”

Pictured: Madagascar is home to two-thirds of the world's chameleon species.

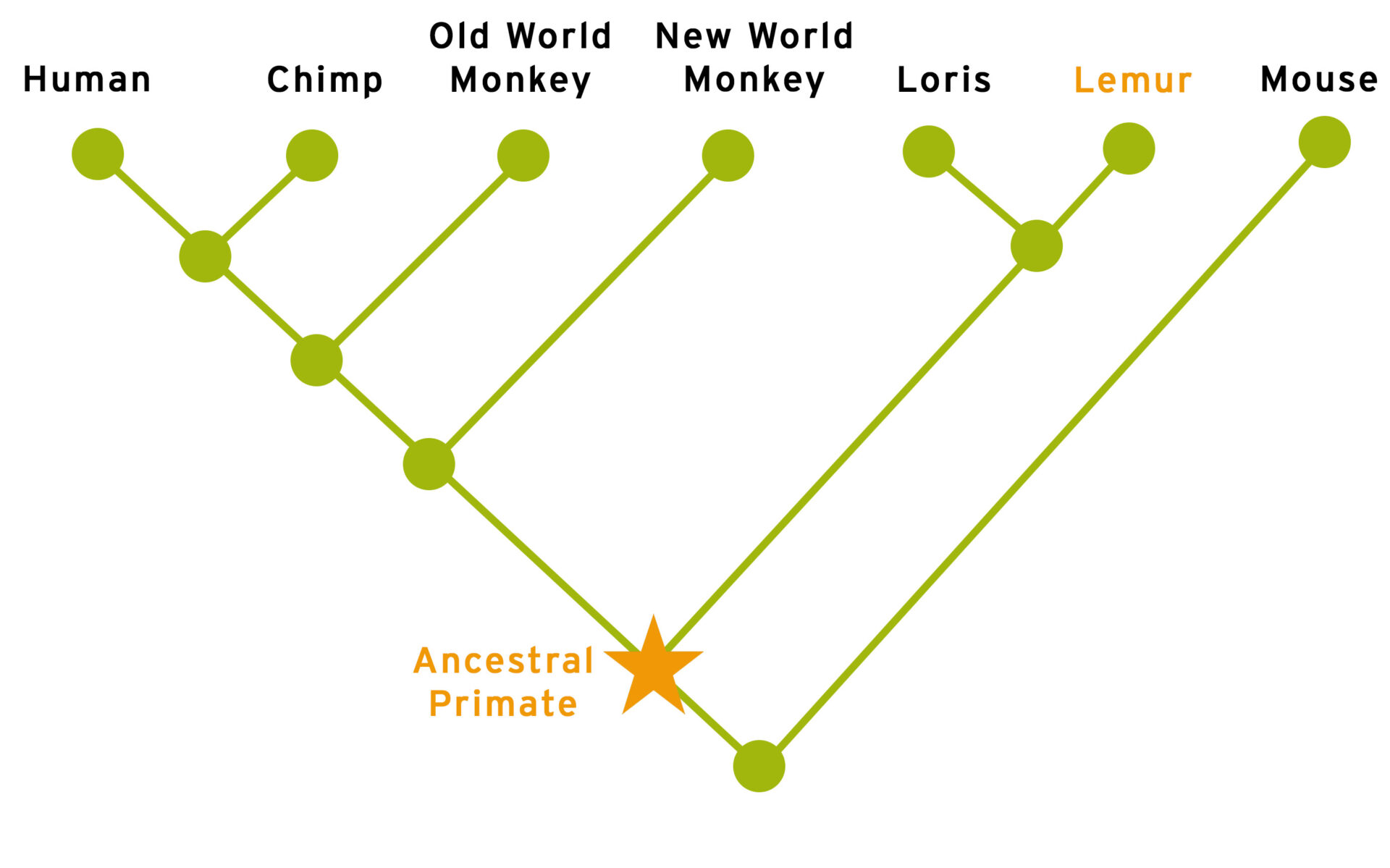

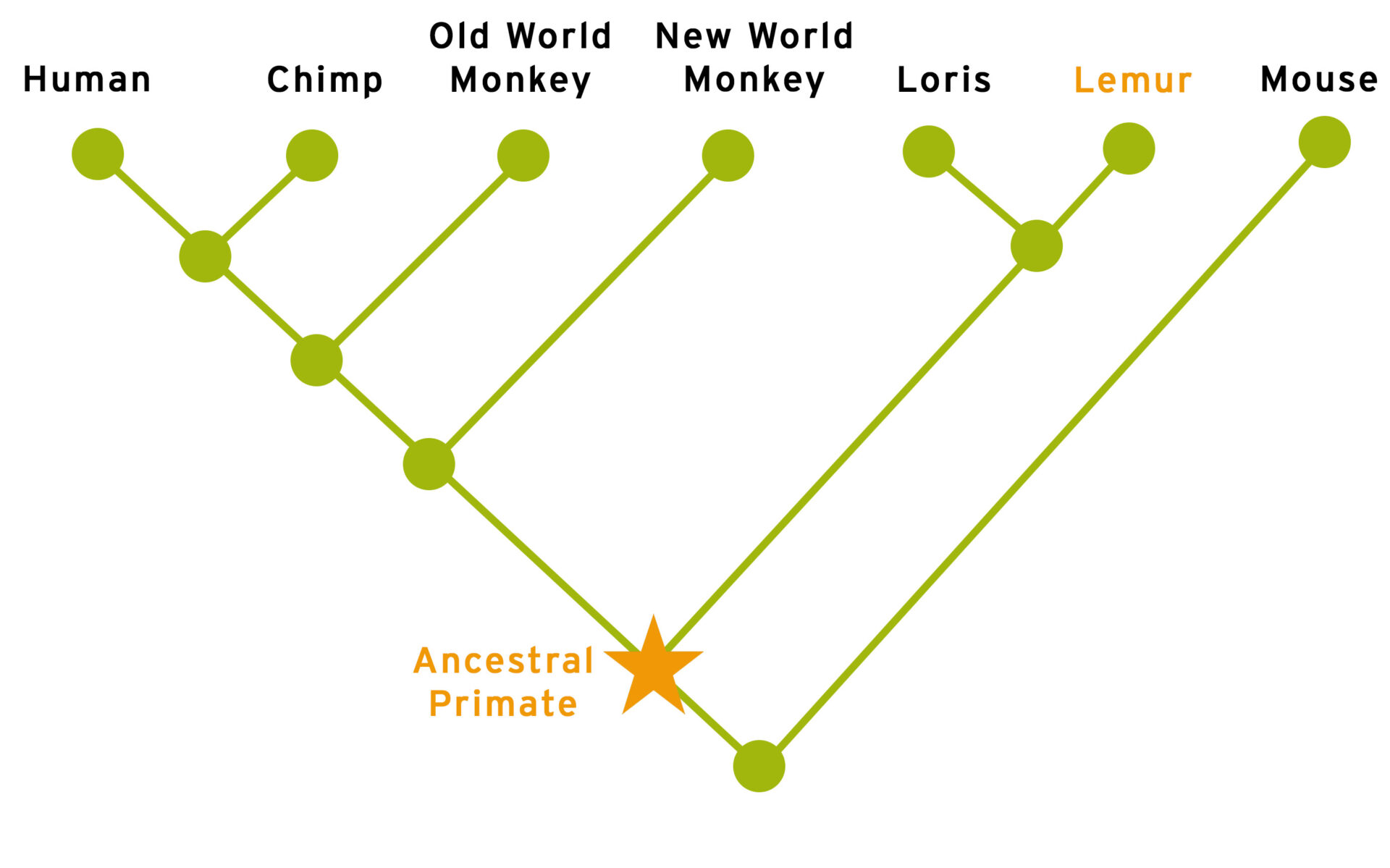

Lemurs are part of our own family tree

As primates, lemurs are our most distant relatives within our own family tree. Studying lemurs within a comparative context across primates allows us to understand ourselves, and the traits and processes that make us both primate and human.

Because the lineage that includes lemurs split from the monkey, ape, and human line millions of years ago, lemurs retain traits that are truly unique among today's primates – and because of their evolutionary age and incredible variety of lifestyles and adaptations, the lemur branch of the primate family tree is particularly interesting to scientists. By non-invasively studying lemurs, DLC researchers gain tremendous insight into primate evolution and human health and behavior. We share with lemurs the vast majority of our genetic code and many of the same diseases, susceptibilities, and health concerns: Studying lemurs could potentially help us find solutions to combat serious problems facing modern society.

For example, some lemur species develop the same plaques and tangles seen in the brains of humans diagnosed with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Others go into seasonal torpor, a form of hibernation, which is unique among primates. Studying these traits in lemurs provide key clues about primate evolution and also now hint at exciting scientific discoveries that will impact humans.

Lemurs hang near the edge of extinction

Since humans arrived on the island 4,000 years ago (Dewar et al. 2013), tremendous deforestation and animal extinctions have occurred. Less than 16% of Madagascar is now covered in forest, and within last 60 years, forest cover has decreased by nearly 40% (Harper et al., 2007). At least 17 species of lemurs (ranging in size from 10kg to 160kg) and many other megafauna, such as the 10-foot-tall elephant bird, have recently gone extinct. Currently, lemurs are considered the most threatened mammal group on earth (Schwitzer et al., 2014).

The island’s human population has ballooned to over 24 million, with more than three-fourths of the population living on less than $1.25 per day. People farm the land to feed their families using traditional methods of slash-and-burn agriculture, which results in loss of soil fertility, erosion, wildfires, and stream sedimentation. Ultimately, the soil is depleted and new patches of forest are burned to create more farmland, with the result that subsistence agriculture is a primary driver of forest loss. The need for land has grown exponentially with Madagascar’s population, which is expected to double by 2050; and the unique biodiversity of Madagascar continues to suffer. Conservation, as the Duke Lemur Center practices, must meet the needs of local communities in addition to protecting the amazing fauna and flora of Madagascar.

At least 17 species of lemur have gone extinct, and the existing lemurs are the most threatened group of mammals on Earth. An assessment by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2018 identified 95% of the remaining 103 lemur taxa as threatened, compared to 74% only four years prior.

It's a race against time to preserve lemur populations, and conservation programs both ex-situ (managed care/zoos) and in-situ (in the wild) are vitally needed.

Pictured: The skull of Megaladapis, an extinct giant lemur, from the collection of the DLC Museum of Natural History. Built somewhat like a koala, the slow-moving Megaladapis was approximately as large as a female gorilla. The species was alive as recently as 650 years ago.

Madagascar is the fourth largest island in the world and features some of Earth’s most amazing and diverse biological life. Isolated for more than 80 million years, the plants and animals of Madagascar spent millions of years evolving their own unique characteristics, not to be found elsewhere on the planet. Remarkably, the more than 100 species of lemurs found in Madagascar exist naturally nowhere else on Earth. Such extreme endemism is characteristic of all forms of life on this oceanic island with 98% of the mammals, reptiles, and amphibians and over 90% of the (more than 12,000) plant species being found nowhere else on the planet.

The sheer size of Madagascar (nearly 1000 miles long and 350 miles wide) coupled with the diversity of Madagascar’s regional climates and habitats—desert, lowland and high altitude rain forest, dry deciduous forest, mountains and valleys, grasslands, spiny forest and knife-edged limestone formations—creates such a vast array of habitats for wildlife and plants that Madagascar is often referred to as the “Eighth Continent.”

Pictured: Madagascar is home to two-thirds of the world's chameleon species.

As primates, lemurs are our most distant relatives within our own family tree. Studying lemurs within a comparative context across primates allows us to understand ourselves, and the traits and processes that make us both primate and human.

Because the lineage that includes lemurs split from the monkey, ape, and human line millions of years ago, lemurs retain traits that are truly unique among today's primates – and because of their evolutionary age and incredible variety of lifestyles and adaptations, the lemur branch of the primate family tree is particularly interesting to scientists. By non-invasively studying lemurs, DLC researchers gain tremendous insight into primate evolution and human health and behavior. We share with lemurs the vast majority of our genetic code and many of the same diseases, susceptibilities, and health concerns: Studying lemurs could potentially help us find solutions to combat serious problems facing modern society.

For example, some lemur species develop the same plaques and tangles seen in the brains of humans diagnosed with dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Others go into seasonal torpor, a form of hibernation, which is unique among primates. Studying these traits in lemurs provide key clues about primate evolution and also now hint at exciting scientific discoveries that will impact humans.

Since humans arrived on the island 4,000 years ago (Dewar et al. 2013), tremendous deforestation and animal extinctions have occurred. Less than 16% of Madagascar is now covered in forest, and within last 60 years, forest cover has decreased by nearly 40% (Harper et al., 2007). At least 17 species of lemurs (ranging in size from 10kg to 160kg) and many other megafauna, such as the 10-foot-tall elephant bird, have recently gone extinct. Currently, lemurs are considered the most threatened mammal group on earth (Schwitzer et al., 2014).

The island’s human population has ballooned to over 24 million, with more than three-fourths of the population living on less than $1.25 per day. People farm the land to feed their families using traditional methods of slash-and-burn agriculture, which results in loss of soil fertility, erosion, wildfires, and stream sedimentation. Ultimately, the soil is depleted and new patches of forest are burned to create more farmland, with the result that subsistence agriculture is a primary driver of forest loss. The need for land has grown exponentially with Madagascar’s population, which is expected to double by 2050; and the unique biodiversity of Madagascar continues to suffer. Conservation, as the Duke Lemur Center practices, must meet the needs of local communities in addition to protecting the amazing fauna and flora of Madagascar.

At least 17 species of lemur have gone extinct, and the existing lemurs are the most threatened group of mammals on Earth. An assessment by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 2018 identified 95% of the remaining 103 lemur taxa as threatened, compared to 74% only four years prior.

It's a race against time to preserve lemur populations, and conservation programs both ex-situ (managed care/zoos) and in-situ (in the wild) are vitally needed.

Pictured: The skull of Megaladapis, an extinct giant lemur, from the collection of the DLC Museum of Natural History. Built somewhat like a koala, the slow-moving Megaladapis was approximately as large as a female gorilla. The species was alive as recently as 650 years ago.

How we’re helping in Madagascar

In-situ and ex-situ conservation programs

The DLC’s focus extends to both in-situ and ex-situ lemur populations on their native island of Madagascar. While our in-situ conservation initiatives focus on lemurs living in their natural habitat (Madagascar’s forests), our ex-situ initiatives address the conservation and care of lemurs living away from the forest in zoos and conservation centers across the island. Ex-situ conservation measures complement in-situ methods in that they provide a genetic safety net (or “insurance policy”) against a species’ extinction in the wild. These measures also have a valuable role to play in recovery programs for endangered species.

Pictured: Black and white ruffed lemurs at Parc Ivoloina, an ex-situ conservation center in Madagascar.

Community-based conservation

The Duke Lemur Center has been involved in conservation efforts in Madagascar for over 35 years. Since the founding of the DLC-SAVA Conservation program in 2011, the Lemur Center’s in-situ (in the wild) conservation efforts have been focused within the SAVA region of northeastern Madagascar (Sambava, Andapa, Vohemar, and Antalaha).

The Duke Lemur Center has been involved in conservation efforts in Madagascar for over 35 years. Since the founding of the DLC-SAVA Conservation program in 2011, the Lemur Center’s in-situ (in the wild) conservation efforts have been focused within the SAVA region of northeastern Madagascar (Sambava, Andapa, Vohemar, and Antalaha).

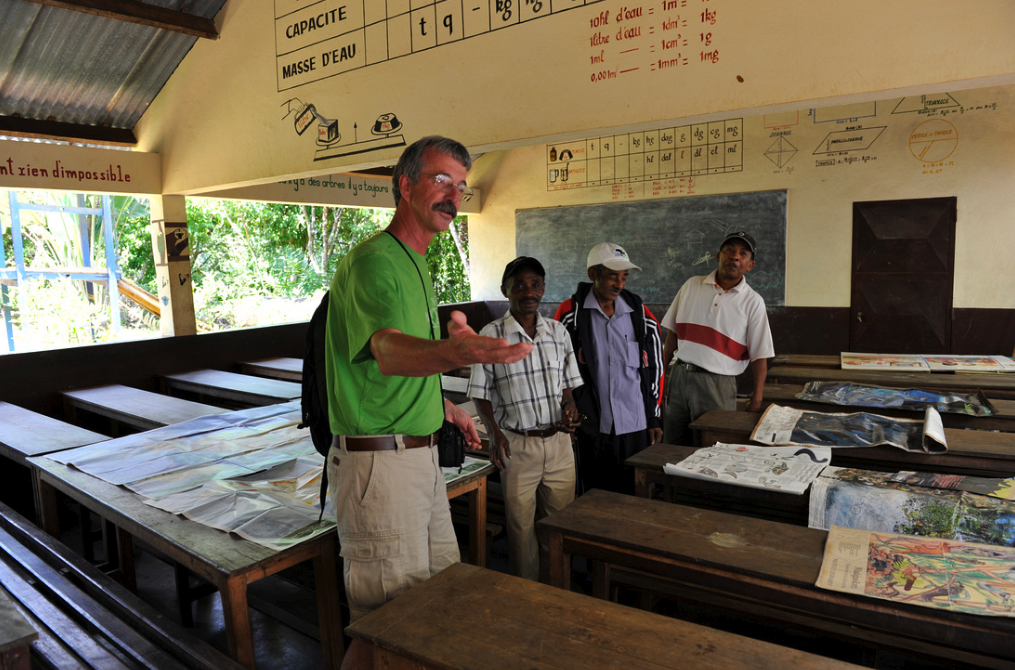

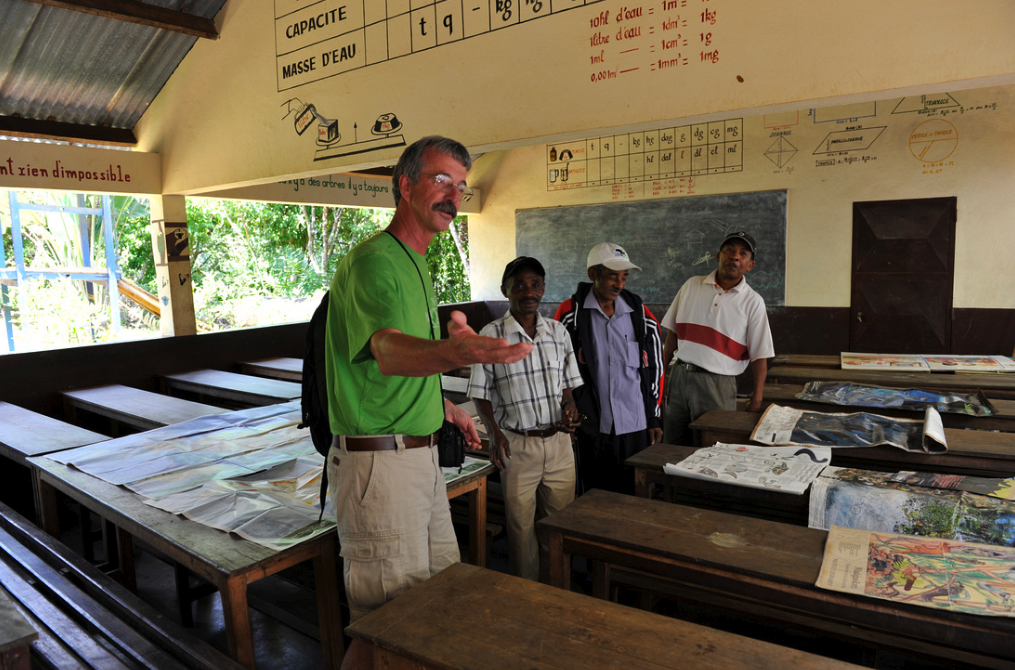

Led by DLC Conservation Coordinator Charlie Welch, the program involves Malagasy staff and Duke students and faculty, all partnering with Malagasy organizations to achieve its conservation goals.

We firmly believe that conservation in Madagascar will be most successful when:

(1) strategies are informed by carefully collected data on how lemurs and humans interact with their natural environment; and

(2) the next generation of Malagasy leaders are inspired by, and have the resources to protect, the remarkable biodiversity of their island home.

Ex-situ lemur initiatives

For more than 50 years, the DLC has built its reputation as a world leader in understanding and caring for lemurs, and our expertise is sought and respected by ex-situ institutions and zoos around the world - including Madagascar! The DLC has partnered with the Government of Madagascar’s Wildlife Department to advance the state of lemur husbandry and breeding management in Madagascar’s zoos: two national zoos and 12 privately-owned zoos, constituting a total of 600+ lemurs across 20 endangered species.

Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group

DLC is a founding and managing member of the Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group (MFG), a consortium of zoos and other institutions committed to supporting conservation in Madagascar. MFG projects in Madagscar focus on community-based conservation techniques operating in the area around Betampona Natural Reserve and Parc Ivoloina on the east coast.

Parc Ivoloina is a regional conservation center on Madagascar’s east coast, which includes a small zoo and focuses on activities such as environmental education and sustainable agricultural practices.

Betampona is a protected natural forest and also the site of the first reintroduction of captive-born lemurs back to the wild, a collaborative DLC/MFG effort. The reintroduction has evolved into an important program of conservation research and ecological monitoring, with education and reforestation components linked to nearby Ivoloina. Thanks in part to DLC support and MFG presence in Betampona, the reserve has been protected from illegal wood cutting and poaching of wildlife. "Perhaps the most valuable result of the restocking program is that the release project became the springboard for a much broader conservation program for Betampona,” says DLC conservationist Andrea Katz.

Pictured above: DLC Conservation Coordinator Charlie Welch conversing with teacher trainers in environmental education (who are also old friends) at Parc Ivoloina. Ivoloina is the site of more than 20 years of conservation work by the Madagascar Fauna Group, of which Duke Lemur Center is a founding and managing member. Charlie and his wife Andrea Katz worked here for 15 years, while living in Madagascar.

Student engagement

The DLC is a major resource for undergraduate and graduate student education:

The Duke Engineers for International Development (DEID) have conducted a water management project, led by undergraduate students to work in the SAVA region.

Through the Duke Global Health Institute, the Bass Connections program has had four vertically-integrated teams of undergraduate, graduate, medical and veterinary students, postdocs, and faculty conduct One Health and Public Health research at Marojejy National Park.

Through DukeEngage, students have helped with conservation and development projects to build and research fish farms, to study lemurs, and much more. All projects are facilitated by DLC-SAVA.

In addition, DLC-SAVA works closely with the local university in the region (CURSA), which trains Malagasy undergraduates in Nature and Environmental Sciences, among other disciplines. We provide scholarships for graduates to attend graduate school in the capital city and pair students with research mentors to conduct new and innovative science in the SAVA region.

The DLC’s focus extends to both in-situ and ex-situ lemur populations on their native island of Madagascar. While our in-situ conservation initiatives focus on lemurs living in their natural habitat (Madagascar’s forests), our ex-situ initiatives address the conservation and care of lemurs living away from the forest in zoos and conservation centers across the island. Ex-situ conservation measures complement in-situ methods in that they provide a genetic safety net (or “insurance policy”) against a species’ extinction in the wild. These measures also have a valuable role to play in recovery programs for endangered species.

Pictured: Black and white ruffed lemurs at Parc Ivoloina, an ex-situ conservation center in Madagascar.

The Duke Lemur Center has been involved in conservation efforts in Madagascar for over 35 years. Since the founding of the DLC-SAVA Conservation program in 2011, the Lemur Center’s in-situ (in the wild) conservation efforts have been focused within the SAVA region of northeastern Madagascar (Sambava, Andapa, Vohemar, and Antalaha).

The Duke Lemur Center has been involved in conservation efforts in Madagascar for over 35 years. Since the founding of the DLC-SAVA Conservation program in 2011, the Lemur Center’s in-situ (in the wild) conservation efforts have been focused within the SAVA region of northeastern Madagascar (Sambava, Andapa, Vohemar, and Antalaha).

Led by DLC Conservation Coordinator Charlie Welch, the program involves Malagasy staff and Duke students and faculty, all partnering with Malagasy organizations to achieve its conservation goals.

We firmly believe that conservation in Madagascar will be most successful when:

(1) strategies are informed by carefully collected data on how lemurs and humans interact with their natural environment; and

(2) the next generation of Malagasy leaders are inspired by, and have the resources to protect, the remarkable biodiversity of their island home.

For more than 50 years, the DLC has built its reputation as a world leader in understanding and caring for lemurs, and our expertise is sought and respected by ex-situ institutions and zoos around the world - including Madagascar! The DLC has partnered with the Government of Madagascar’s Wildlife Department to advance the state of lemur husbandry and breeding management in Madagascar’s zoos: two national zoos and 12 privately-owned zoos, constituting a total of 600+ lemurs across 20 endangered species.

DLC is a founding and managing member of the Madagascar Fauna and Flora Group (MFG), a consortium of zoos and other institutions committed to supporting conservation in Madagascar. MFG projects in Madagscar focus on community-based conservation techniques operating in the area around Betampona Natural Reserve and Parc Ivoloina on the east coast.

Parc Ivoloina is a regional conservation center on Madagascar’s east coast, which includes a small zoo and focuses on activities such as environmental education and sustainable agricultural practices.

Betampona is a protected natural forest and also the site of the first reintroduction of captive-born lemurs back to the wild, a collaborative DLC/MFG effort. The reintroduction has evolved into an important program of conservation research and ecological monitoring, with education and reforestation components linked to nearby Ivoloina. Thanks in part to DLC support and MFG presence in Betampona, the reserve has been protected from illegal wood cutting and poaching of wildlife. "Perhaps the most valuable result of the restocking program is that the release project became the springboard for a much broader conservation program for Betampona,” says DLC conservationist Andrea Katz.

Pictured above: DLC Conservation Coordinator Charlie Welch conversing with teacher trainers in environmental education (who are also old friends) at Parc Ivoloina. Ivoloina is the site of more than 20 years of conservation work by the Madagascar Fauna Group, of which Duke Lemur Center is a founding and managing member. Charlie and his wife Andrea Katz worked here for 15 years, while living in Madagascar.

The DLC is a major resource for undergraduate and graduate student education:

The Duke Engineers for International Development (DEID) have conducted a water management project, led by undergraduate students to work in the SAVA region.

Through the Duke Global Health Institute, the Bass Connections program has had four vertically-integrated teams of undergraduate, graduate, medical and veterinary students, postdocs, and faculty conduct One Health and Public Health research at Marojejy National Park.

Through DukeEngage, students have helped with conservation and development projects to build and research fish farms, to study lemurs, and much more. All projects are facilitated by DLC-SAVA.

In addition, DLC-SAVA works closely with the local university in the region (CURSA), which trains Malagasy undergraduates in Nature and Environmental Sciences, among other disciplines. We provide scholarships for graduates to attend graduate school in the capital city and pair students with research mentors to conduct new and innovative science in the SAVA region.

How you can help

The DLC’s conservation projects in Madagascar are run exclusively on grants and donor funding. Please consider making a tax-deductible donation today! All gifts to Madagascar Programs will be directed to the areas and initiatives listed below. Many of these areas include the involvement of undergraduate and graduate students in planning, research, implementation, and analysis—inspiring the next generation of conservation and science leaders.

In-situ conservation programs supporting environmentally sustainable ways of life: fuel-efficient cook stoves (reducing fuel needed for cooking), reforestation, sustainable agriculture training (alternative crops, fish farming), green charcoal with bamboo, family planning and women’s reproductive health, protection of Marojejy National Park in collaboration with Madagascar National Parks, empowering local conservation committees and training community rangers—ensuring that law enforcement is locally led and benefits are shared

Education programs to raise awareness about the importance of lemurs and interest in environmental conservation: in-school visits and environmental activities, class field trips into the forests of northeastern Madagascar, teacher training in environmental education, urban outreach events and campaigns—including posters in restaurants and partnerships with hotel owners—to reinforce that lemurs should not be eaten

Research programs to help us better understand lemurs and their natural environment: fauna and flora surveys and research missions in SAVA (northeastern) region of Madagascar, landscape restoration, soil health and infectious disease research, logistical support and collaboration with visiting researchers

Ex-situ lemur conservation, management, and welfare in Madagascar: in partnership with the Government of Madagascar, build local capacity via training of Malagasy zoo staff, produce a comprehensive lemur care manual in Malagasy and French, develop a standardized animal record system for use in Madagascar zoos, establish the foundation for cooperation and animal exchanges for breeding programs, and develop guidelines for the management of confiscated and illegally held lemurs